Nothingness

and Thanksgiving

There is a cliche, which I find terribly tragic:

“We can’t appreciate what we have until it’s gone.”

While it’s certainly true that we often don’t appreciate the gifts we have until we lose — or nearly lose them — to doom ourselves to not appreciate what we have until we experience loss is a horrific proposition.

It’s also false.

In order to explain why it’s false, and how we can develop a mindset to live with more consistent, sustainable, radical appreciation, I ask you to join me on a short exploration about nothing.

I’ll never forget how my physics professor in college described to us what existed before the big bang:

“What existed before the big bang is what you see behind your head.”

We don’t see nothing behind our heads. In fact, if one were to see nothing behind his or her head, a visit to the neurologist would be in order. We simply don’t see behind our heads.

Analogously, there is quite simply no before the beginning of the universe.

This requires some explanation.

When we picture “nothing” we naturally think of a vast empty space with time passing by silently.

However, the nothingness out of which the universe came to be is far more nothing than this.

Let’s break this down some more.

The big bang theory continues to be, nearly a hundred years after its inception in 1924, the most widely accepted and well-supported scientific theory of the origin of the universe. It proposed a revolution in cosmology that shattered previous conceptions by suggesting that the universe had a beginning — a notion that would have been anathema to any intellectual for the 2+ millennia since Aristotle, who “proved” logically that the universe had always existed.1 Even the fiercely independent thinker Albert Einstein drank Aristotle’s proverbial kool-aid and refused to believe that the universe had an origin (even when staring at the same data that led to the discovery of the big bang years later by Edwin Hubble). The question that the big bang would beg was too immense for him to confront: how could everything emerge out of nothing?

Let’s consider carefully: when physicists speak of the universe being 13.8 billion years old, they don’t just mean the stuff in the universe is that old. Rather, they mean to say that even the universe itself — where all that stuff exists — the very fabric of space-time — is 13.8 billion years old.

This means two important things:

Once you rewind time 13.8 billion years, there is no further back you can rewind, hence, there can be no before the big bang — time itself is that old.

The big bang didn’t occur somewhere in outer space — the whole notion of space came into being as the big bang banged.

Meditating on this for a bit will help you grasp the ungraspable nothingness in which the universe is so-to-speak suspended.2

What existed before the big bang is indeed what we see behind our heads.

While we think of empty space as nothing, it’s really not. Space is a thing. There was a time in which even space didn’t exist. When time = 0, space = 0.3

True nothing is less than no thing. It’s nothing. Whatsoever.

Zilch.

Zero.

Nada.

אפס.

0.

__________. (I wish I could convey it with words or symbols but there are none that can do this adequately.)

To summarize: absolutely everything that exists emerged out of that absolute nothing.4

The devastating question that reverberates from this cataclysmic realization is how can something emerge from utter nothing? Surely “nothing” doesn’t possess the ability to make anything, since, of course, it’s nothing.

This most important question is beyond the scope of this XL, but among the most important questions a human being can ask.5

The direction we want to take this is:

how might our awareness of this backdrop of nothingness change our lives for the better?

We started with the cliche that “we can’t appreciate what we have until it’s gone.” It’s not true. We most definitely can, but to do so, we must reset the defaults in our minds back to true zero.

Here’s what I mean:

Human beings have a cognitive tendency to reset “normal” to wherever we find ourselves at that time, or wherever we think the people around us find themselves. Both come with severe side-effects.

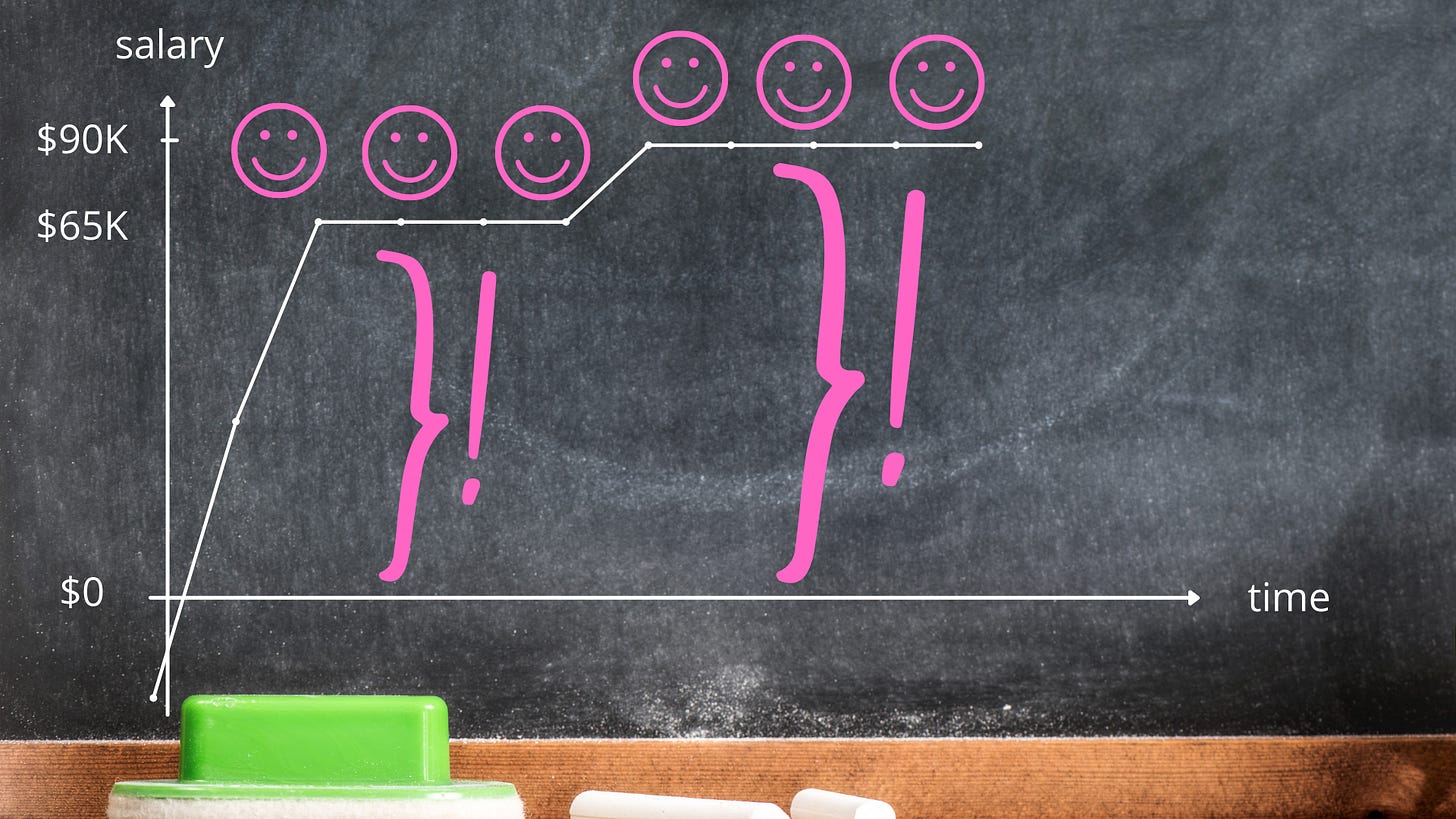

When a kid graduates college, and gets her first job, she’s ecstatic. As her net income comes out of the red at -$90,000 (with tuition and rent and expenses) and into the black with a salary of +$65,000, she feels elated…

…until, of course, that salary becomes the new normal in her mind.

At which point she feels nothing.

If this status quo persists, she will at some point start to even feel bad about what she’s making, especially if she sees peers getting raises and promotions.

The same salary went from making her feel good to feeling meh to now making her feel bad. How can this be??

It’s not until she gets a promotion herself that she feels a boost of satisfaction again, but alas that satisfaction too fades with time…

The explanation of this phenomenon is that human beings are creatures of habit. We get used to things. We get used to anything actually. In fact, there’s no amount of wealth on planet earth that will on its own make a person perpetually appreciative. This is mind boggling, but if you look around, you’ll see that it’s true. The reason is because we are always resetting our zero, and therefore feel that we’re back at square one, when really we’ve come a long way.

The masterkey for radical and sustainable appreciation is preserving true zero as the x-axis. For a person to say, “I’ve got nothing going for me,” or “Nothing seems to be working out,” bespeaks of deep lack of understanding of what nothing is.

Often, if I’m having a touch week, I view a video of Nick Vujicic who was born with no arms and no legs, and displays seemingly unending energy based on gratitude for the blessings he does have. To date, he’s spoken to over 2 million people as an inspirational speaker. It is nearly impossible to not be inspired by seeing a person beaming with happiness despite his lacking such fundamental assets such as limbs (!).

I once met an older man who told me that when he was a young man, he and his wife would go out of their way on their daily commute to work to drive through the poorer neighborhoods in town. He never told his wife that the reason he would take this route was because he wanted them to maintain perspective on the immense blessings they had. He remarked that the default of people was to kvetch about what they don’t have. To stop kvetching we have to start stretching our minds beyond their default modalities.

Meditating regularly on what not having truly looks like pops one’s perspective back out to see reality as it is — in all its grandeur. This is the only way to maintain appreciation for what we have, and keep the x-axis where it belongs — at true zero.

We don’t have to become poor to appreciate our wealth, but we do need to think about being poor to appreciate what we have.

We need to work mentally to do this. Before we eat, the ancient Jewish practice is to contemplate a world without this kind of food.6 When we open our eyes in the morning, the ancient Jewish practice is to imagine life without vision.7 We do the same thing when we stand up straight, get dressed, put on our shoes, and successfully go to the bathroom, recognizing what would happen if God forbid our bodies would fail to filter out and expel the toxins we consume.

These practices help us normalize our vision of the universe as a creation from nothing, and allow us to stay appreciative even when certain physical blessings flatten out and becomes status quo.

The Jewish calendar actually celebrates Thanksgiving 52 times a year (53 if you count Thanksgiving).

Every Shabbat.

The song of Shabbat is the song of thanksgiving (Tov Lehodot LaHashem —טוב להודות לה׳) .8 But what about Shabbat makes it an especially good time for giving thanks?

Shabbat allows us to experientially recognize that the universe was created.9 Like a work of art that demands of the artist to step back and appreciate it, the universe and our lives that take place in it are the ultimate works of art. To not see them on the backdrop of the blank canvas — and even no canvas when they started — is to deny the Divine creativity that brought them into being, and miss out on endless appreciation.

Happy thanksgiving and Shabbat shalom.

Of course, the Torah inescapably presents a universe that had a beginning. It’s opening phrase is, after all, “In the beginning of Elohim’s creating the Heavens and the Earth…”

I personally find it mind-boggling to consider that the prodigious 13th-century Spanish scholar of Jewish law and mysticism Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman (Nachmanides/Ramban) quotes the earliest extant kabbalistic text called the Book of Formation, which states that initially, “[God] made that which was nothing something.” The Ramban goes on to explain, “Now with this creation, which was like a very small point having no substance, everything in the heavens and on the earth was created.” This description is logically absurd, but it is an astonishingly precise premonition of the initial singularity proposed by the big bang theory six centuries later.

For the record, I am speaking here in secular, scientific terms, but according to Kabbalah, the nothingness אין I am referring to here is more accurately called אין סוף — the Infinite, which is beyond words or description of any sort. It is indeed “nothing” — nothing like anything that exists in our dimension of existence — in that It lacks all limitations and definitions.

Picturing nothing as a black hole is even more of a misnomer. A black hole is very much “a thing.” It’s just that there is so much stuff in a black hole that the gravitational pull sucks in even light itself.

There is a special word in hebrew for this. While human creativity consists of giving shape to and recombining things that already exists (יצירה), creation from utter nothing is called בריאה. The Latin philosophical jargon is ex nihilo, “[creation] from nothing.”

Here are the words of Ramban: “The Holy One, blessed be He, created all things from absolute non-existence. Now, we have no expression in the sacred language for bringing forth something from nothing other than the word bara (ברא).”

The energetic arrow of purpose we pondered two weeks ago is forged in the voltage between being and this nothingness, and the vital becoming of existence we explored last week can now be seen as bursting into reality out of that vacuum of being. Meditating on these simple but profound ideas will undoubtedly help a person perceive God in ways most people never have the opportunity to experience.

“Borei pri ha’etz — Who created [ex nihilo] the fruit of the tree” asks of us to consider this fruit to have possibly not existed at all. See footnote 4.

A life-changing exercise is to think of the amount of money you would accept in exchange for your eyeballs.

…I imagine the numbers keep scrolling higher and higher in your head, and you’re still not selling. Whatever number you’re at, you’re essentially saying that when you wake up in the morning and open your eyes, you’re waking up with at least millions or billions of dollar worth of assets in your head. Why don’t we do this exercise and others like it more often?! We are so out of touch with our personal wealth.

מִזְמוֹר שִׁיר לְיוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת׃ טוֹב לְהֹדוֹת לַה’ וּלְזַמֵּר לְשִׁמְךָ עֶלְיוֹן׃

A psalm. A song for the day of Shabbat: it is good to thank Hashem, to sing hymns to Your Name on high.

Shemot 31:16-17: “The Israelite people shall keep Shabbat, observing Shabbat throughout the ages as an eternal covenant. It shall be a sign for all time between Me and the people of Israel that in six days Hashem made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day He ceased from work and rested.”

Yes, I agree that it is always important to be grateful to be living at a time (and place) when we have sanitation, medicine and technology.

However, I really find that I personally need to set my baseline higher than what I’m used to in order to have motivation eg to apply to lots of jobs or upskill.

I am frequently grateful for things like washing machines and dishwashers, but when it comes to applying to some exclusive firm or preparing for a difficult exam, I definitely need a different mindset - one which is far more materialistic.