Khein

Doesn't translate well

By now, we should be pretty familiar with the notion that the Hebrew language is a highly economical language. While English has, according to some linguists, around a million lexemes (core words), Biblical Hebrew has only around 10,000.

The reason Hebrew can afford to be so lean on lexemes is that many words can branch out in meaning from a single, shared 3-letter root (shoresh-שרש). If you’re interested in learning Hebrew, this is great news, because the learning curve is bent in your favor. Once you start recognizing roots, you can start figuring out words in context relatively quickly. It’s this linguistic elegance that is partially responsible for the remarkably high literacy rates in Jews in the ancient world.

“the learning curve of Hebrew is bent in your favor!”

While many people are familiar with the 3-letter root system, most don’t realize that the system goes much deeper. 3-letter roots are generally organized according to their 2-letter roots.1

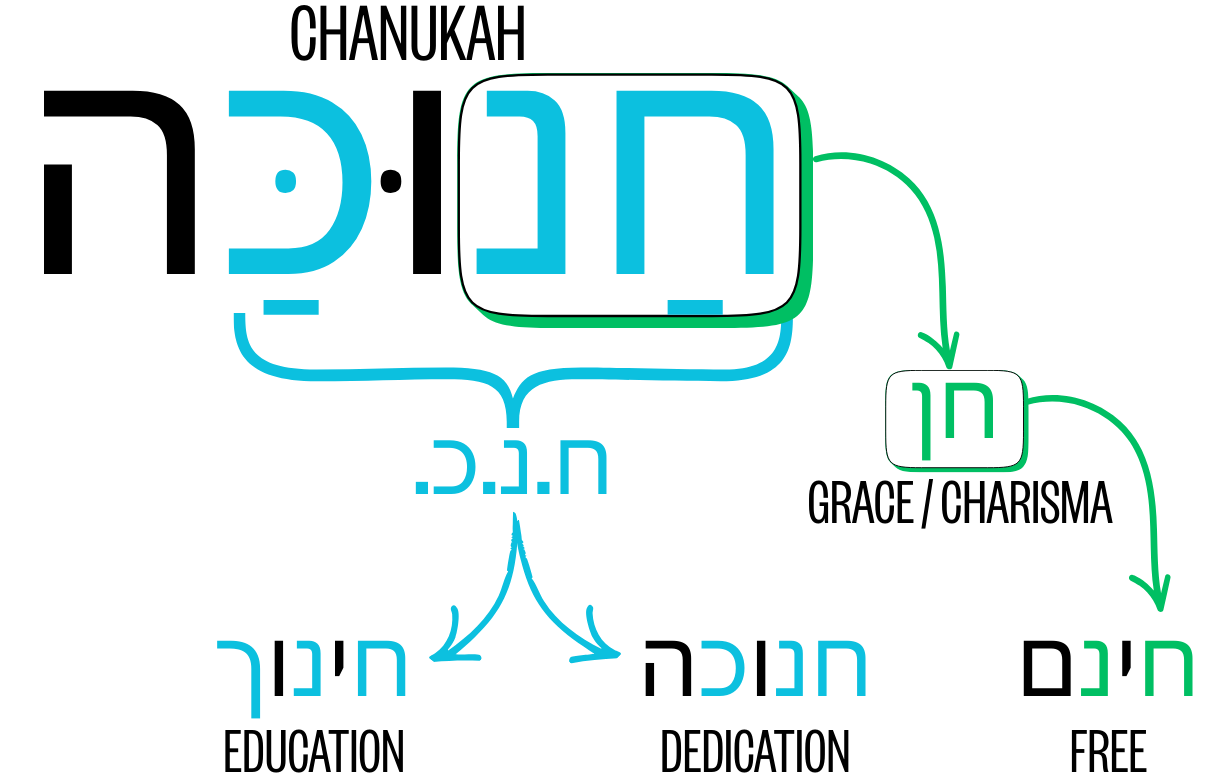

Let’s take, for example, the holiday of Chanukah (חנוכה), which has in its name the root khet–nun–kaf (ח־נ־כ), which, as we explored a few weeks ago, literally means “dedication,” but it also shares a root with the word khinuch (חינוך) — “education.”

The first thing to note here is that education is meant to function like a dedication ceremony — or like the rededication of the Temple that the Maccabees led after their hard won battle against the Seleucid Greeks.

Education is not merely the transfer of information, but is meant to be a celebratory push along the growth trajectory in which a student is meant to travel on over the course of their lives. The Hebrew word “חנוכה” teaches us that dedication is what drives education, and that Jewish education was at the heart of the Macabbees’ rededication of the Temple.

“The word ‘חנוכה’ teaches us that dedication is what drives education.”

But what’s at the heart of this dedication? What exactly are we trying to cultivate in our education?

If you look at the word חנוכה, you’ll find that there’s a 2-letter root within that 3-letter root — the root of the root — in this case, the word khein (חן).

Khein (חן) is an elusive word that appears throughout Tanakh. It captured the curiosity of the Greeks themselves in their attempts to translate the Torah, known as the Septuagint. The sages of the Talmud understood Ptolemy II’s intention in commissioning the translation as an attempt to subsume and suppress the teachings of the Torah, reducing it to just another book in their library.2

In the Septuagint, the word khein — as in “Noach found khein in the eyes of God — נֹחַ מָצָא חֵן בְּעֵינֵי ה׳”, or “Yosef found khein in the eyes of [his master] — וַיִּמְצָא יוֹסֵף חֵן בְּעֵינָיו” — is translated as “charis,” which means “grace” or “favor,” related to the English word “charisma.”

This, however, begs the question: what’s charisma?

As a word, “charisma” is simultaneously shiny and opaque. Most people have a strong sense of what it is because they’ve seen people who possess it, but it’s hard for them to put their fingers on what it is. It’s a je ne sais quoi, an “I-don’t-know-what-it-is” (IYKYK in modern parlance). Charisma, it seems, is a “secret sauce” that makes people likable, but what exactly we like about them remains obscured.

The Hebrew, on the other hand, does two things. Firstly, by calling it khein (חן), it recognizes the mystery of our attraction to certain people. It does this by associating the word khein (חן) with the word chinam (חינם), which means “free.” You like them, but you don’t know what they’ve done to earn your approval, which you’ve essentially given to them for free.

A closer look at the word khein (חן) reveals why.

The opening piece of the Chassidic master Rebbe Nachman of Breslov’s magnum opus, Likutei Moharan centers around khein, and resolves this paradox.

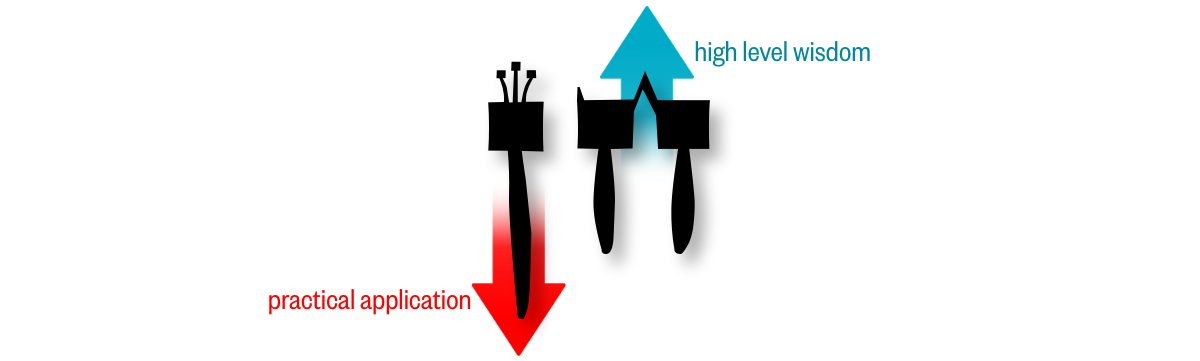

He explains that this 2-letter word can be broken down even further into its letters. The letter chet (ח) represents khochmah (חכמה) — Divine wisdom. If you look at the way chet is written in a Torah scroll, you’ll see an arrow pointing upwards (the chatoteret). It points toward a grasp of something above its head — which is the essence of wisdom. Wisdom, in Jewish consciousness, is not information or intelligence, but rather the reception of a life force, a perspective and vision that flows down from above, as it says in Kohelet: “wisdom gives life to those who possess it — הַחׇכְמָה תְּחַיֶּה בְעָלֶיהָ“ and “wisdom makes a person’s face shine — חָכְמַת אָדָם תָּאִיר פָּנָיו.” It’s for this reason that many have said that the pinnacle of wisdom — the crown on the head of the wise — is to know how much he does not know — how much is above his head.

The nun (ן), continues Rebbe Nachman, represents the precise opposite end of the spectrum of life from wisdom. It represents the concept known in Kabbalistic texts as malchut (מלכות) — kingship — the ability to practically apply wisdom in the world.3 It’s for this reason that the “final nun” (ן) is written as a line that starts up top and continues down into the “ground.” It is also the letter of constant practice and resilience, which are the hallmarks of bringing ideas into reality. A person who lied once shiker-שקר, but a liar who lies habitually is a shakran-שקרן.

If you put these two ideas together, you start to get a picture of what khein is — and what it is about people who captivate us even before they’ve achieved anything per se. Those who try to stretch themselves to grasp ideas that they don’t readily understand, and to practically apply those ideas to the best of their abilities, inspires in those around them, attraction and admiration. The khein is there even before they’ve achieved anything.

The greatest illustration of khein is kids. Kids — when their curiosities haven’t been blunted by brain rot — are constantly stretching themselves to understand things “above their pay grade” and experiment with those new ideas in their world. When we put aside the mess they might make in the process, we feel khein towards them.

It’s this natural desire to stretch in both directions that education is meant to cultivate. We all possessed this khein as kids, but when we stopped cultivating it, we started losing it.

“We all possessed this khein as kids, but when we stopped cultivating it, we started losing it.”

Ask kids in 1st grade, “who thinks of themselves as an artist?” Tons of hands will shoot up.

“Who here is a little scientist?” Again, many kids who enjoy science will identify as scientists.

Ask kids in 8th grade the same questions. Far fewer hands.

Tragically, we tend to lose our khein as we stop growing, and stop stretching ourselves.

The Jewish notion of education is not about transferring information. Nor is it about expanding proficiencies, per se. It’s about cultivating this khein. It’s about preserving and developing this quality that children have naturally — of curiosity, of boldness, of willingness to experiment and to apply this wisdom in the world, each person in his own way.

This is the same thing we find so compelling about the Maccabees. A small army — which wasn’t really an army at all — but a family of kohanim, priests, who primarily identified themselves in their service in the Beit HaMikdash (Temple). But when the time came, and they realized that it was do or die — they pushed themselves. They understood that they had to stretch out of their comfort zones, and face a military force much greater than they — and would fight however long it took to defeat them.

And they did.

And when they finally did, and they arrived at the Beit HaMikdash, they pushed themselves again. They knew that somewhere there must be pure oil — even though there was no rational reason to believe that there should be. They committed themselves to searching until they would find it.

And they did.

The message in the miracle of the oil is that it also stretched beyond its normal limits — and burned for eight days. It’s precisely this khein-חן that has carried the holiday of Chanukah-חנוכה for millennia in the hearts and minds of millions of Jews.

May we find the khein in ourselves and in the people around us — the khein we all possessed from childhood — and reawaken it as adults, to stretch ourselves to grasp ideas we may have considered above our heads, and be bold enough to make them realities. May we find khein in Hashem’s eyes. And may we see the world stretch around us — with khein.

For more XL on Chanukah, read this 👇

If you find this stuff interesting, you would probably appreciate the Etymological Dictionary based on the linguistic teachings of Rabbi Samson Refael Hirsch.

Fascinatingly, the translation of the Torah into Greek is one of the events mourned on the fast day following Channukah, known as “Asara B’Tevet,” the 10th day of the month of Tevet. The reason it is a cause for mourning is because of the “flattening” and distortion of the Torah’s Divine wisdom through translation.

The word manon (מנון) means “king” (as in Mishlei 29:21).

Nice graphics and message! I like the way you laid out your post.