Initiation

is the essence of education

Education is not about information. It’s about initiation.

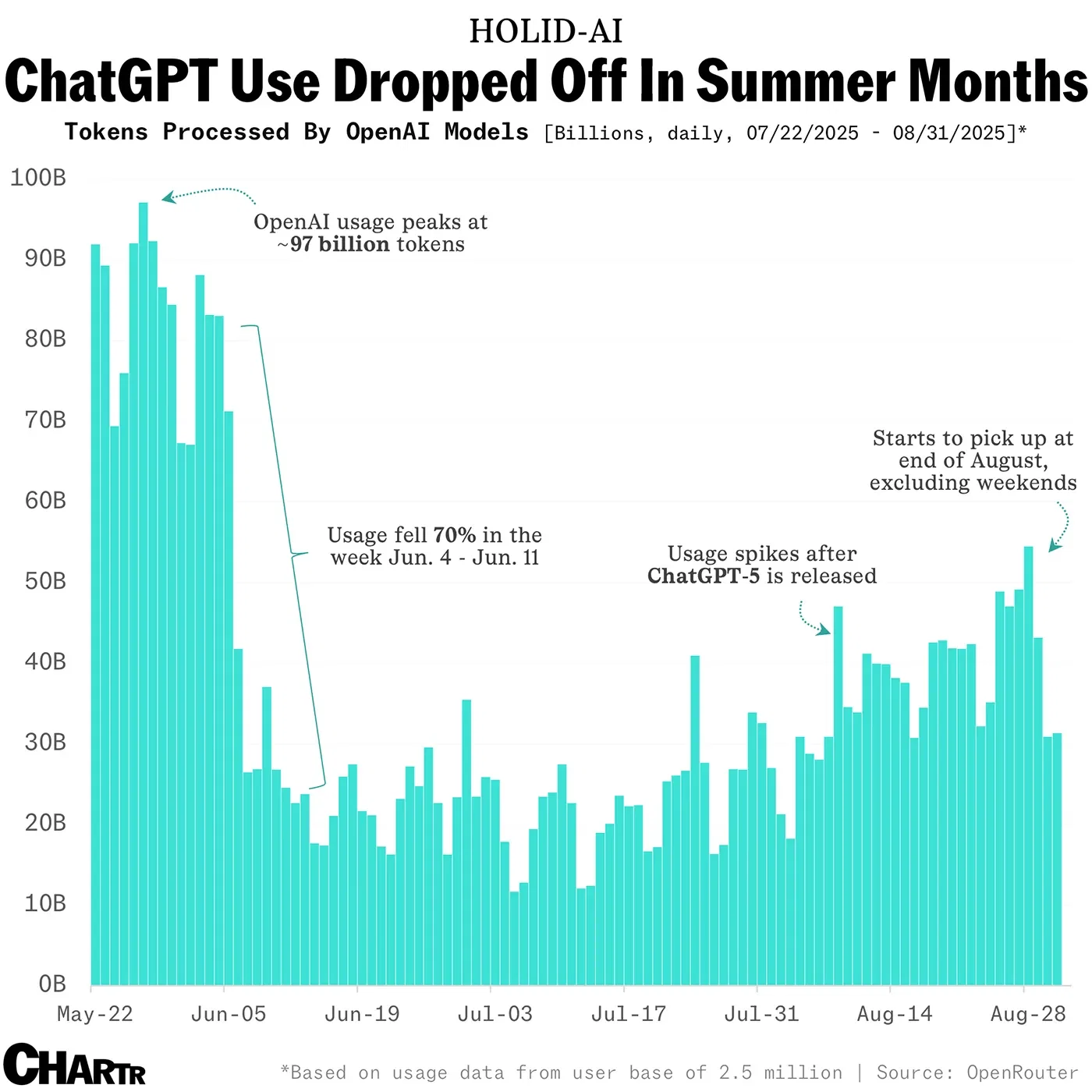

If you walk the halls of a high school in 2025, and as you do, peak at kids’ laptops, you’ll see them playing video games, on Snapchat, watching videos on YouTube, or sometimes doing shopping. If they happen to be doing school work, they’re probably using ChatGPT.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that virtually all homework done by teenagers today is done with the help of AI (if not entirely by AI). This may not alarm you because, at this point, you also use AI quite a bit. So do I.

The massive difference is: if you graduated high school when dial up modems took a minute or so to connect to the internet, or prior, you had no choice but to learn how to think for yourself. Of course, plagiarism has existed since time immemorial, but even the plagiarists had to do some thinking about how to plagiarize back in the 90s.

Here’s the issue:

If you don’t learn how to think when you’re a full time student, when will you learn how to think?

If you are a thinking person, and through your own efforts, over many years, you’ve discovered your own voice, and style, and convictions, so then AI is a tool you wield, no different than spellcheck, a thesaurus, an encyclopedia and a word processor. But if you’ve never learned to think for yourself, and never had to put in effort, you are a tool wielded by artificial intelligence and the companies that design it.

I am not a Luddite, and this isn’t another prophecy of doom about technology, but I do believe that this is one of the big hairy societal problems we have today. If we’re not concerned about it, and not thinking about it, we won’t adapt our educational approaches fast enough to avoid its dangerous pitfalls.

If you’re not convinced that this is cause for concern, I recommend that you have a conversation with a teenager. Try to convince them that it’s important for them to learn to write on their own — without AI.

“When will I have to write anything on my own in the future?”

Even if they don’t, they definitely will have to think in the future. I’m willing to bet that they haven’t thought about that.

For decades, we have been told that we have entered a shiny, new “Information Age,” in which the entire universe is literally at our fingertips, and at worst, in our pockets. However, we were not told, or trained, or more importantly, educated to flourish as humans in this new age. And it feels like nothing could have prepared us for AI.

When information can be accessed in fractions of a second, and research papers produced in a matter of minutes, we need a new notion about what education is.

Or perhaps an old one.

“When information can be accessed in fractions of a second, and research papers produced in a matter of minutes, we need a new notion about what education is.

“Or perhaps an old one.”

The Hebrew word for education is Khinukh-חינוך.

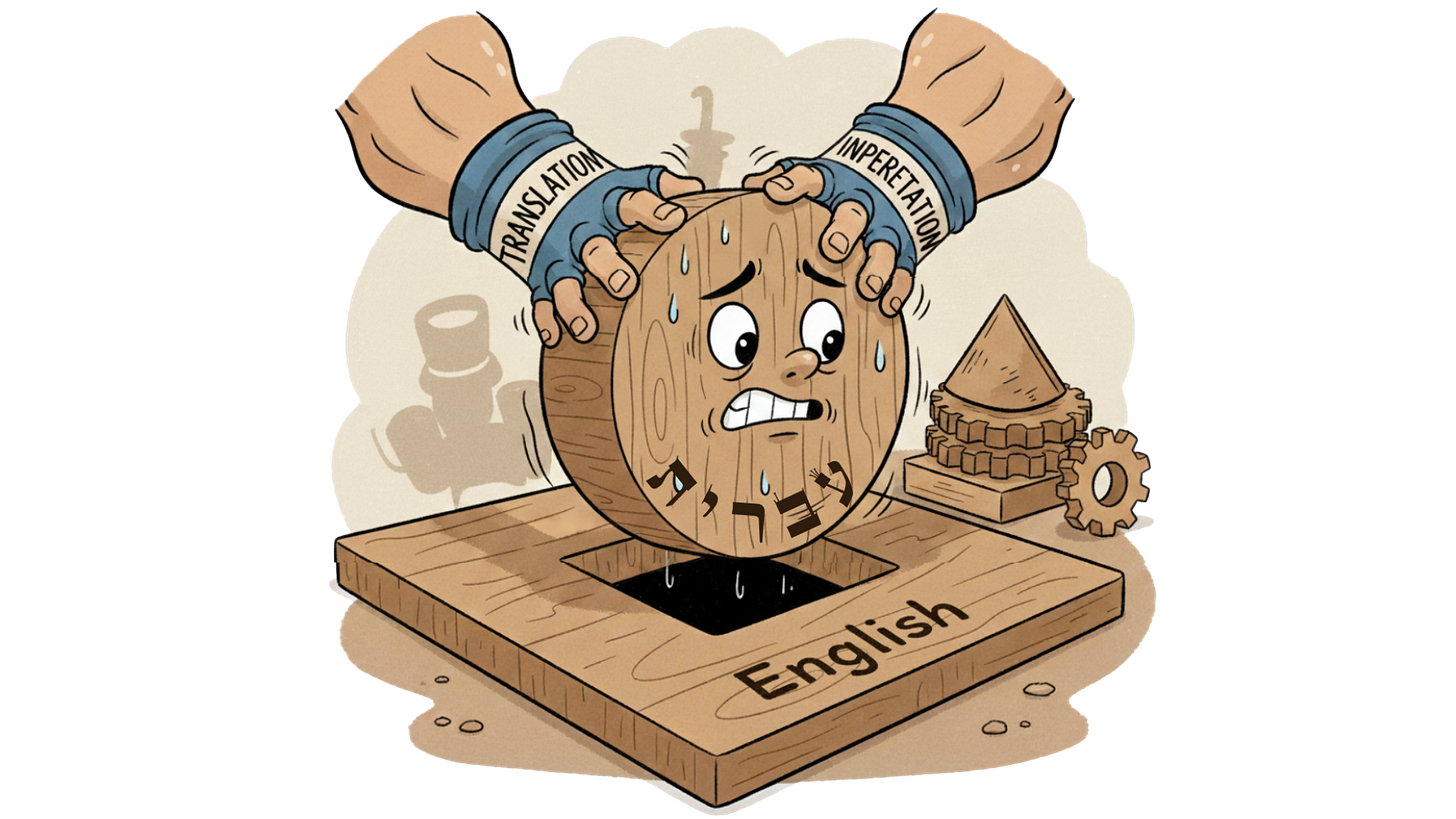

As we’ve encountered many times in the Language of Life Series, the problem with 1-to-1 translations is that they end up squeezing round concepts from a one language into the square holes of analogous concepts of another language. Languages were not created in coordination with one another. As a result, words never neatly translate from one language to the other. Something is always lost in translation.

We might assume that the Torah’s concept of khinukh-חינוך means the same thing as what “education” means to most traditionally educated English speakers today. But, of course, it doesn’t.

Most people’s experience of Western education is of memorization and regurgitation. This was the issue that struck a chord with tens of millions of viewers of Sir Ken Robinson’s 2006 TED Talk, one of the most listened-to talks on their platform. This reveals that the problem with modern education is not modernity per se — it’s not ChatGPT and MathGPT — it’s that an underlying view of education was always superficial, just waiting to be exposed as such by AI.1

The word khinukh-חינוך comes from the same word as Chanukah-חנוכה, which literally means “inauguration” since the holiday of Chanukah celebrated the re-inauguration of the alter in the Beit HaMikdash (Temple) after it had been defiled for years by the Syrio-Greeks.

The question is:

What does inauguration have to do with education?

Think about the high level tasks you do at work. The sophisticated processes people pay you for: complex analysis, surgery, therapy, diagnosing problems, negotiating deals.

You didn’t learn how to do any of these things by watching YouTube videos. Nor did you learn how to do them by reading about them in a textbook. Ultimately, your education began when you were given a chance to do it yourself — that terrifying moment that a mentor believed in you and let you climb into the cockpit and fly — even though you weren’t fully (or even partially) qualified yet.

This brave moment of initiation — and a celebratory inauguration — is the essence of education.

It’s a brave moment for students, and it’s a brave moment for their teachers who allow them to try (and fail) for the first time.

When the Torah provides a window into what God saw and loved in Avraham it doesn’t merely speak of his belief in Him as a religious person. It focuses of his belief in people as an educator.

Bereishit 18:19:

…כִּי יְדַעְתִּיו לְמַעַן אֲשֶׁר יְצַוֶּה אֶת־בָּנָיו וְאֶת־בֵּיתוֹ אַחֲרָיו וְשָׁמְרוּ דֶּרֶךְ ה׳ לַעֲשׂוֹת צְדָקָה וּמִשְׁפָּט

For I know and love about him that he instructs his children and his household after him to keep the path of Hashem by doing what is just and right…

Note that Avraham’s teachings are not described as static information or even spiritual secrets, but as “a path” that we learn to walk on.

“…Avraham’s teachings are not described as static information or even spiritual secrets, but as “a path” that we learn to walk on.”

One example that comes to mind of how Avraham would actually do this is when he had the opportunity to host hungry merchants beaten down by the desert sun, he didn’t just do the mitzvah of taking care of their needs on his own. Nor did he rely on some sort of esoteric osmosis of role-modeling in which the members of his household would somehow learn to be kind from his example while they sat on the couch doomscrolling on Tiktok.

Avraham would get them involved. He trusted them to do the job with him.

Bereishit 18:7-8:

וַיְמַהֵר אַבְרָהָם הָאֹהֱלָה אֶל־שָׂרָה וַיֹּאמֶר מַהֲרִי שְׁלֹשׁ סְאִים קֶמַח סֹלֶת לוּשִׁי וַעֲשִׂי עֻגוֹת׃ וְאֶל־הַבָּקָר רָץ אַבְרָהָם וַיִּקַּח בֶּן־בָּקָר רַךְ וָטוֹב וַיִּתֵּן אֶל־הַנַּעַר וַיְמַהֵר לַעֲשׂוֹת אֹתוֹ׃

Abraham hastened into the tent to Sarah, and said, “Quick, three seahs of choice flour! Knead and make cakes!” Then Abraham ran to the herd, took a calf, tender and choice, and gave it to the young man who rushed to prepare it.

Rashi, ad loc:

אל הנער. זֶה יִשְׁמָעֵאל, לְחַנְּכוֹ בְּמִצְוֹת

“to the young man” — this was [his son] Ishmael [whom he asked to take care of preparing the meat] to educate him in the performance of mitzvot.

Expensive social-emotional curriculums that talk about kindness may make us feel like we’ve done our due diligence in educating our kids to be caring, but this is not education (khinuch-חינוך) at all. The actual kindness-education happens when people actually start down the path of kindness by being kind. Even if they don’t get it right the first (which they won’t), the most important thing is happening: they’re starting.

It’s for this reason that only when Avraham gets news of his nephew being taking hostage, and responds right away by mobilizing his students from their studies to go fight that they are called his disciples, khanikhav-חניכיו:

Bereishit 14:14 (see Rashi):

וַיִּשְׁמַע אַבְרָם כִּי נִשְׁבָּה אָחִיו וַיָּרֶק אֶת־חֲנִיכָיו יְלִידֵי בֵיתוֹ שְׁמֹנָה עָשָׂר וּשְׁלֹשׁ מֵאוֹת וַיִּרְדֹּף עַד־דָּן׃

When Avram heard that his brother was taken captive, he mobilized his disciples, born in his own house, three hundred and eighteen, and pursued the [enemy] to Dan.

Only when they’ve been mobilized are they called “his disciples.”

“Only when they’ve been mobilized are they called ‘his disciples.’”

Artificial Intelligence is and will remain a challenge in education, but the real problem lies not in the technology, but in how we think about what education is — and if we’re thinking at all.

Zohar Atkins at Second Voice helped me understand this. Check out Second Voice for a fascinating exploration of AI and the future of humans.

Thank you Rabbi Jack. I loved this! I had been wondering what education is now given Chat GPT.

Mid, cliche, undeveloped