Idologies

And the questions that threaten them

Some thoughtful readers wrote to me this week in response to our last post. Let’s be totally clear: ANY idea can become an end unto itself. When ideas becomes ends unto themselves they become “deified” as gods. When an ideology becomes an idology, invariably individuals get sacrificed in service of its cult. Why wouldn’t they?

As we noted two XL’s ago, we are not claiming that Torah ideas are exempt from this phenomenon. If people were to idolize any single idea from Torah, they would come to sacrifice people to it as if it were a god — just as they would any other irresistible idea that swept them off their feet. One example that comes to mind is a notion that captivated many in the Orthodox world post-Holocaust: the idea of sending hundreds of thousands of children through a yeshiva system that wasn’t institutionally geared towards their education but rather towards the production of “Torah giants” on the other side at the expense of those who didn’t “make it.” This was justified in an era in which our leadership had been decimated and new leaders were looked to as the solution.1

This intellectual idol has been painstakingly smashed by modern Jewish history as many families suffered watching their children either flounder or just drift away in a school system that wasn’t interested in their success per se. Today, there is thankfully an immense proliferation of specialized yeshivas and seminaries for all kinds of kids with different needs.2

I mention this as an example lest readers think we weren’t being even-handed in our critique. As you can guess, I’m a big fan of the Torah and yeshivas are the very best settings for learning Torah. However, if we pursue study as an end unto itself, like all idologies, it ironically self-destructs.3

Critical thinking and questioning is one of the hallmarks of the methodology of Torah study, and it was Abraham’s preferred method of dismantling idologies.

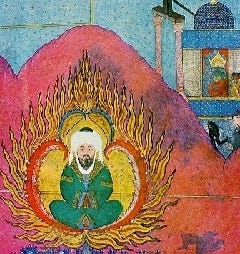

In the well-known midrashic allegory describing an exchange between Abraham and the philosopher-king Nimrod, Nimrod attempts to coerce Abraham to worship fire or be killed by it (a literal sacrificing of an individual to an idol/ogy). Abraham responds by suggesting “why not water since it puts out fire?” Nimrod acquiesces as it’s a reasonable suggestion. To which Abraham then suggests that they worship clouds “which carry water.” Wow, great point. This goes on a few more times until Nimrod has enough Talmudic back-and-forth for one day, and has Abraham thrown into the fire. He wasn’t moved by Abraham’s methodology it seems, but we can be.

Questions give voice to our conscience — sincere ones do at least.

Abraham’s movement was different from those it stood against because it was not one of ideological indoctrination but of intellectual liberation.

Ideologies and the cults that surround them resist questioning, but honesty and integrity demand it.

“Why?”

“Because X.”

But why X and not Y?”

“Because that’s just the way it is!”

Great question. Bad answer.

Torah asks of us to ask our questions.

What does the expression “the Expression of Life” mean anyway?

For a deep dive into classic and contemporary Torah sources about individuality and self-esteem in our self-education and our education and guidance of others, check out Nurture their Nature, now available on Amazon with Prime delivery.

To be clear, this perspective was more of a post facto justification for an education system that burgeoned post-Holocaust — not some sort of sinister plan from the outset. Additionally, what we’re describing is not reflective of how most thoughtful educators actually looked at their work, but rather how many rationalized how it made sense to push the average teenager to study with an intensity that was traditionally reserved only for the intellectual elite.

The book I co-authored on individuality in education, Nurture their Nature (now available on Amazon) was written precisely to strengthen the movement towards education tailored to each student. The book demonstrates how this outlook as always been the cornerstone of Jewish education, but was popularized into a household phrase by King Solomon: “educate the youth according to his own path so that when he grows old, he won’t stray from it”.

The Maharal in his introduction to his Tiferet Yisrael, explains this concept in light of the Talmud’s question: “why is it so uncommon for Torah scholars to [born from parents] who are Torah scholars?”