Unique

Truly One of a Kind

One of the many crimes against the English language according to my legendary high school English teacher Mrs Marie Miller (of blessed memory) was the error of one saying or writing the phrase “very unique.”

“A person or thing cannot be ‘very unique.’

‘Unique’ means ‘one of a kind.’ One is either unique or he is not.

There is no such thing as being ‘very unique,’ or ‘somewhat unique,’ for that matter.”

-Mrs Marie Miller

This error is more than just grammatical. It reflects the superficiality of our sense of individuality. The things we might assume make us stand out in certain settings are discovered to be commonplace in others. This realization can be upsetting. A so-called “genius” in high school can have a minor identity crisis when she arrives at her Ivy League campus and finds herself to be average.

A personal anecdote that comes to mind is that I ironically stopped wearing a kippah when I spent a gap year in Israel after having started wearing one when I was a senior in my mostly non-Jewish public high school. What I had thought made me unique in my rural Connecticut hometown dissolved upon arrival in Jerusalem. A shallow sense of individuality is inevitably revealed as such.

It is this same superficiality about what makes us unique that is the source of our fear of being replaced by AI bots. Our reliance on ChatGPT (and other LLMs) to accomplish so many annoying tasks we used to do ourselves belies our anxiety that we’ll be replaced by them.

But the opposite should be true. Artificial intelligence begs the question as to what is real intelligence.

What is the essence of who we are?

What makes me irreplaceable?

It is axiomatic in Jewish consciousness that every single human being is a unique phenomenon in the history of the universe. No where else on planet Earth is there someone who contributes to the mosaic of humanity what you do. Not now. Not ever.

What about identical twins?

No one challenges the fact that although identical twins share the same DNA, their personalities can be quite different. Modern science, averse to the existence of a immeasurable soul, once believed that the personalities of identical twins diverged exclusively due to environmental differences. This theory found did not find scientific support as personality differences existed whether or not twins were raised in the same home. Minor environmental differences could not be said to account for major personality differences.1

People are, of course, affected by their environments. All of us, without exception, are forged by our times, our societies and cultures, our parents and families, our schools, our shuls and our workplaces — even our own bodies undoubtedly shape the people we are. But Judaism does not see personality as exclusively determined by that which is outside of it.

The human spirit is not a chunk of tofu that merely absorbs the flavors it comes in contact with.

Nor is the human being like the hollow “eye of the storm” surrounded by environmental factors raging around it.

At the center of the person is his unique, Divine essence.

While people are influenced by their environments, they still possess a fundamental personality that is essentially theirs. Uniqueness begins there. AI can simulate everything else, but it is merely amalgamating factors externally. It cannot synthesize this inner uniqueness.

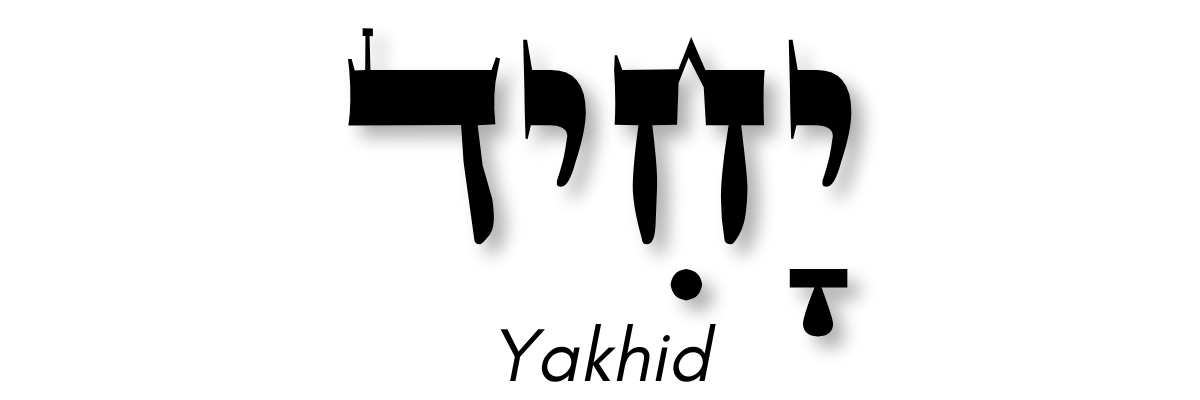

The word “unique” in English was borrowed from French, and originally from the word unus in Latin, meaning “one.” Similarly, in Hebrew the word for “unique” is Yakhid-יחיד. It is related to the much better known word Ekhad-אחד, also meaning “one.”

In this way, a person who manages to tap into his God-given uniqueness (יחידיותו), connects with God’s Uniqueness (אחדותו).2

God is Unique in His Uniqueness because by definition there is no One other than Him, but a person who shines his or her unique light is doing something no one else can. It can therefore be said that your uniqueness is as real as God’s.

It is for this reason that the passuk (verse) in the Torah that describes the human being as “made in the image of God,” first makes the point that every single human being is made “each in his own image” despite all descending from the same original Adam and Eve.

Bereishit 1:27:

וַיִּבְרָא אֱלֹקִים אֶת־הָאָדָם בְּצַלְמוֹ בְּצֶלֶם אֱלֹקִים בָּרָא אֹתוֹ זָכָר וּנְקֵבָה בָּרָא אֹתָם׃

So God created mankind in his own [unique] image,3 in the image of God He created him — male and female He created them.

The unique color of light that shines into and through every person’s consciousness is the key to understanding the Image of God.

The Talmud refers to the crucible of identity that is the Image of God as a press, like one mints coins. This press can be understood as the combination of a person’s uniqueness within pressing against a person’s unique circumstances without. My soul’s essence is unique AND my life circumstances are unique. I am forged through my decisions between both.4

Uniqueness is not a New Age fad. I mean it is, but it’s so much deeper than the way it’s presented.

Individuality in pop culture is about “your personal brand” and “your unique look.” While there is something to this, it does not begin to scratch the surface of the uniqueness that connects us to the Unique One. A deeper sense of our own uniqueness also allows us to appreciate the uniqueness of others against whom we are not competing. In the immortal words of Mrs Miller:

“You cannot be ‘very unique.’ You either are unique or you are not.”

To read more about the profound understanding of individuality in Torah consciousness, please read the book I coauthored with my dear friend Rabbi Dr Yosef Lynn Nurture their Nature, on sale today.

To order a copy, send $12/copy to any one of the following payment options, and include your U.S. mailing address in the note (after Monday, the price goes back up to $18 including shipping, which is still less than Amazon).

Venmo: @rabbijackcohen

Paypal: jackcohenperel@gmail.com

Zelle: jackcohenperel@gmail.com

A few years ago, researches began to think about how small differences in experience can lead to broad personality divergence between initially almost identical brains due to neuroplasticity (see this NPR article on it).

The Talmud attributes God’s unique relationship with Avraham from his youth to Avraham’s being a יחיד like God Himself:

Pesachim 118a

“.אֲנִי יָחִיד בְּעוֹלָמִי וְהוּא יָחִיד בְּעוֹלָמוֹ, נָאֶה לַיָּחִיד לְהַצִּיל אֶת הַיָּחִיד”

“I am Unique in My world, and he is unique in his world. It is fitting for One Who is Unique to save one who is unique.”

Most English translations seem to translate בצלמו as “His image” with a capital “H,” as in “God’s image.” This is not Rashi’s understanding who understands that it is first saying “the i[ndividual’s unique] image” followed by “in the image of God He created him.” Otherwise it would be redundant and grammatically odd by first using a pronoun to refer to God, and then identifying it. It seems clear that it is precisely this point that is made by the Mishna in Sanhedrin 38a.

If you understand uniqueness as including life circumstances, you can understand why the axiom of uniqueness is not contradicted by the Kabbalistic notion of reincarnation. Even if the entire soul were to come back in another person, in another place, at another time — the two people would be different. They would see themselves reflected in one another while still being unique.

In all due respect to Ms.Miller...

Something can be unique in some societies or contexts, but be very common in others.

Thus, "very unique" means that it is unique in very many (or all) societies or contexts.

Oh this is beautiful when you began speaking about us having been created in G_D’s image.