Science

and the pursuit of oneness

This is Part 1 to a New 6-Part Series on God’s Unity

Science is not the enemy.

Scientism is.

What is “scientism?”

If you’ve lived through the early 2020s, you are probably quite familiar with what scientism looks like. Scientism is the belief that science is the only way to figure out what is real and true in the world. Naturally, it also leads devout scientists to overstate how accurate their scientific conclusions are — usually before they are…conclusive.

Good scientists recognize the fallibility of science.

This admission actually helps them produce better results because it prevents dogma and hubris from eclipsing truth — however it may turn out to look like. Since the experimental method is predicated on replacing wrong theories with better theories, the more humble the scientist, the faster he or she will move on from a model of nature that has been demonstrated to no longer work.

My wife Calanit’s psychology professor Dan Gilbert wisely opened up his Intro to Psychology course at Harvard with the following classic line:

About half of what I’m about to start teaching you will be proven false in the next fifty to a hundred years. I just don’t know which half — so I’m going to teach you all of it.

One of my own physics professors in college said something similar to us:

There’s false advertisement in your textbook.

Truthfully, every science textbook should open with a disclaimer that says something like this:

DISCLAIMER: The content of this book is only what we believe to be true at this point, but we know for a fact that we will have to revise some of it in the future. We’ve already seen that some of these theories presented within these pages break down under certain extreme conditions. We just haven’t yet developed better ones. We’re working on it and will get back to you!

This XL is the first in a series exploring the Unity of All of Things — arguably the central idea of all Jewish thought.

Now that we’ve got the scientism-bashing out of the way, we can begin by speaking about what makes science so valuable — not just for its monetization value in informing technologies that can be sold to consumers — but more profoundly — to help us come to know God.

Rabbi Elijah Kramer, one of the greatest Torah scholars of the last thousand years, and globally renowned by Jews and Gentiles alike as “the Genius of Vilna” for his mastery of Jewish law, mysticism and the natural sciences, was quoted by one of his disciples as teaching:

to the extent that one lacks knowledge of the natural forces, he will lack one hundred-fold in the wisdom of the Torah.1

Just as an example of what this means:

The plague of the firstborn, the tenth plague in Egypt can look to the untrained eye like “just another miracle,” unless one has a working knowledge of genetics. Unlike some miracles, like the splitting of the sea, which could be explained as a very well-timed and well-aimed wind, the sudden, simultaneous death of only the firstborn citizens of a given country has no coherent mechanism in biology to explain it, putting it in its own category as a miracle.

Moses Maimonides, like the Genius of Vilna, was easily one of the most influential Jewish scholars in the last two thousand years. He himself was also a scientist, and chose to open his seminal work on Jewish law with the injunction to study and meditate on nature as “the path to love and revere God.” He also included in it numerous principles of science as they were understood in his time. Maimonides saw science as literally “foundational” to the study and observance of the Torah, calling this opening section “The Foundations of Torah.”

Science is not the enemy of monotheistic religion.

On the contrary: science systematically looks for the Oneness that unites the diverse array of phenomena we observe in the Universe.

And so should we.

How, exactly, is science “looking for Oneness?”

(And why am I capitalizing the word “Oneness?”)

When Charles Darwin was working on his theory of natural selection, he was deeply troubled by the existence of peacock tails. He wrote, somewhat comically, to his friend and colleague:

The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me feel sick.

Why?? Peacocks are some of the most magnificent looking creatures on the planet!

Precisely for this reason. Darwin could not figure out how evolution didn’t rapidly eliminate such a large, attention-grabbing apparatus awkwardly attached to these birds’ tushes. It makes them sitting ducks (err…peacocks) for predators!

These sorts of questions keep scientists up at night.

Why, though? Why can’t they just simply say: “this corner of the world functions according to different rules,” and leave it that??

The answer is:

Whether they know it or not, scientists are on a quest for coherence. Their grand project is to uncover the unity of everything.

Since science has not yet discovered the Grand Unifying Theory of Everything, the theories we have only partially unify the universe and the phenomena in it.

In order to get to a more unifying theory, the less unifying theory has to break down.

Here’s a classic example:

At some point, medieval astronomers became disturbed when they observed planets doing funky stuff (“retrograde motion”) in the sky when they were “supposed to be” moving in perfect circles around the earth — a theory which was understood as perfectly logical since the time of Pythagoras in ancient Greece.

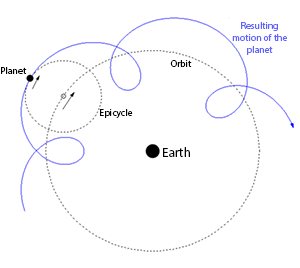

In order to keep what they thought was a unified theory that all planets move in circles, and the sacred assumption that Earth was at the center of the universe, they had to come up with something called “epicycles” where everything orbitted the Earth but also moved in little sub-orbits. This is what explained their funky motions.

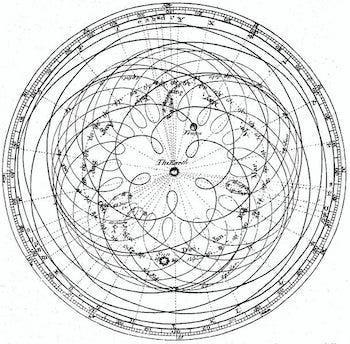

Within a matter of time, the theory of epicycles got really messy, as you can see:

Not without a fight, Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler managed to overcome the assumption of an earth-centered universe and the fixation on circular orbits in favor of heliocentrism and a new model of elliptical orbits. A new, more elegantly unified theory was born.

The unity of the universe shone through it more brightly.

These days, it seems more common and more comfortable for people to say, “the universe has your back” than “God is looking out for you.”

And, to be honest, I can see why.

The universe is visible and tangible.

God is not.

The universe can be measured and modeled with great precision with cutting edge scientific tools like the James Webb Space Telescope and the CERN Large Hadron Collider.

You can scan the skies for God for a looong time — you ain’t gonna find Him there.

The understandably leaves the modern, thinking person much more prone to lean into the idea of “the universe” than the seemingly abstract notion of “God.”

…but what if instead of trying to find God through the lenses of telescopes and microscopes, we could use the whole universe itself as the lens to “see” God?

Well, that would be really cool.

That’s exactly where we’re heading. I hope you join us on the journey!