Real Intelligence: Part 1

Contrasting RI with AI

I first realized that we had a major problem on our hands in the fall of 2012. I had just returned to the US to serve as a rabbi for college students after six years of studying Talmud and Jewish philosophy in Jerusalem, and I was experiencing some culture shock — in the culture I was raised in.

The community I had spent that prior chapter of my life has an attitude towards technology that ranged from “suspicious” to “antagonistic.” Part of this aversion was cultural. Technology is seen by most of the Ultra Orthodox Jewish community in Israel as opening the doors wide to influences that are considered dangerously seductive, particularly to young people.

The other part, however, is principled. Torah study sits at the sacred center of the Orthodox world. Taking a shortcut in learning could be compared to offering a sacrifice from stolen goods.

If you didn’t invest effort to acquire it, how can it be considered yours to offer?

Talmud Megillah 6b:

Rabbi Yitzkhak said:

If a person says to you: “I have worked hard and not found [success in my studies],” don’t believe him.

[Similarly, if he says to you:] “I have not worked hard but [regardless] found [success in my studies],” don’t believe him.

[If, however, he says to you:] “I have worked hard and have found [success in my studies],” [you can] believe him.

Learning is meant to be hard.1 And hard it was.

There were practically no shortcuts available to us in my yeshiva2.

The fonts of the Talmud come in three sizes: tiny, tinier, and tiniest. Its pages are filled with footnotes and sidenotes, commentaries, and commentaries on commentaries. My flip phone was obviously not equipped with Google Translate, and certainly not with ChatGPT. I had nothing except a thick, physical dictionary to help me break down the dense Aramaic vocabulary devoid of vowels or punctuation.

There were no CliffNotes to the Talmud (thank you, Cliff for getting me through high school and college). And if you’re wondering: what about the ubiquitous Artscroll translation of the Talmud? At that time, it was considered contraband in those hallowed halls.

It doesn’t help that the legal cases that the Talmud deals with are, at first glance, abstruse and archaic. And most challenging for me, the Talmud’s logic is endlessly layered, ever-branching into diverging opinions, and opinions on those opinions. To be honest, after 20 years, I still find Talmud as dizzying as it is dazzling.

Nothing about the external packaging of the Talmud is alluring. I’ve come to absolutely love it, but back then, the only thing pulling me to study it was the millennia-old assurance that there was life-changing meaning to be found in its study.

Any delicious whiff of Divine meaning I had gleaned from the more accessible, contemporary English books on Judaism was sourced in the Talmud and Zohar, and the rich Hebrew library that surrounds them. I felt that I owed it to myself to push through my deep-seated aversion to Talmud that I had developed in my early teenage years. I would never forgive myself for not trying as an adult to break through to the pleasure of learning Talmud.

At some point, it became clear to me that I would only find meaning and relevance in the Talmud through my own concentration, effort, and contemplation. My teachers, supportive as they were, couldn’t concentrate or contemplate on my behalf. The best they could do was answer my questions, correct my mistaken assumptions, and guide me through the infinitely ornate maze of Jewish texts.

“It became clear to me that I would only find meaning and relevance in the Talmud through my own concentration, effort, and contemplation.

“My teachers, supportive as they were, couldn’t concentrate or contemplate on my behalf.”

After two decades of cramming my way through some of the top public and private schools in the country, I had arrived at the oldest, continuous educational tradition in the world without any way to hack it. My success or failure as a Talmud learner would depend wholly on my own effort.

Back to the fall of 2012 and realizing that the old fashioned, black-and-white Jews of Jerusalem might be onto something:

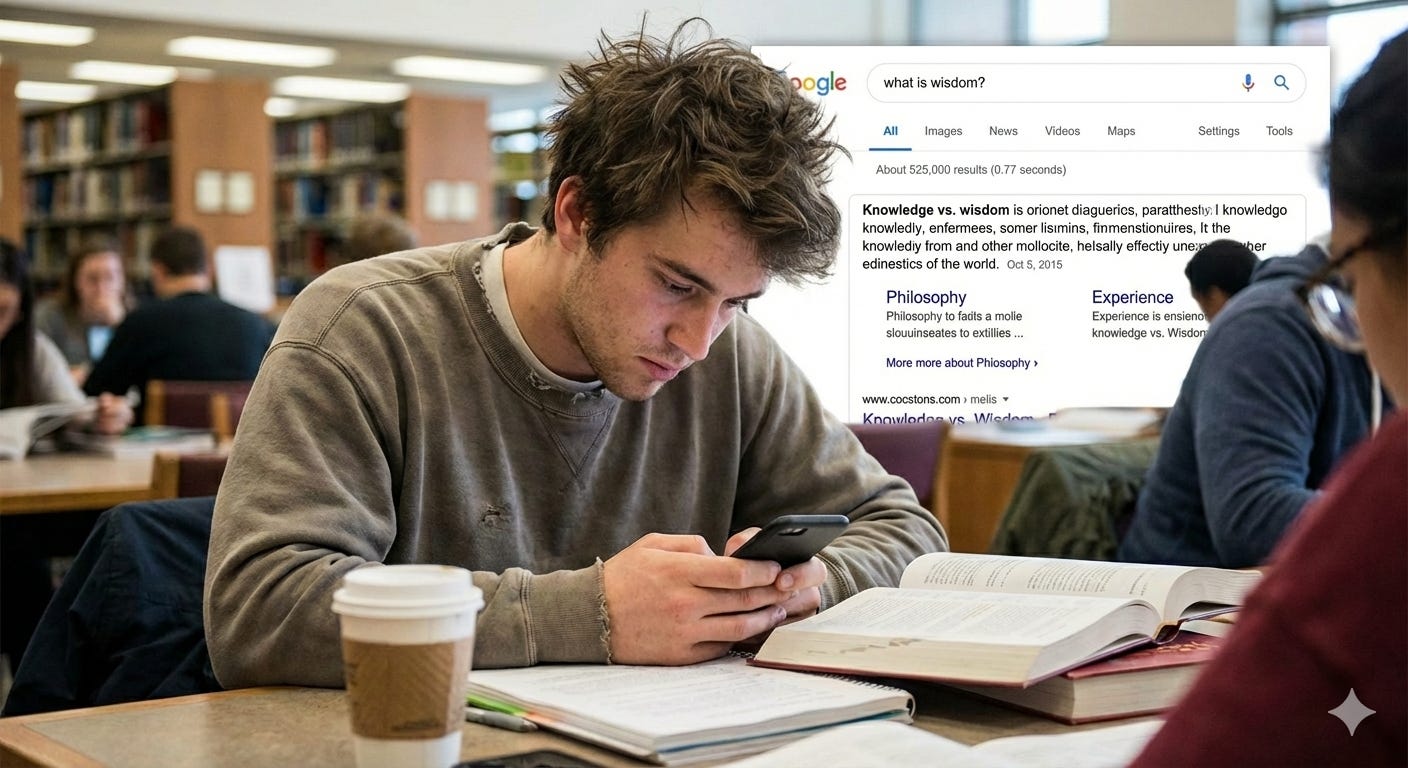

It was my first full-time job, and I was being onboarded by Rabbi Shmuel Lynn at the University of Pennsylvania. I watched carefully as he led the opening session of his “Maimonides Fellowship,” a 10-part “Intro to Judaism” course that he would recruit for through a combination of charm and a modest stipend that students would “earn” upon completion. After warming up the crowd with some jokes and pop culture references, Rabbi Lynn asked the group to turn to the person next to them and together come up with a definition of "wisdom.”

A third of them instinctively pulled out their phones and Googled “wisdom.”

Wide-eyed, I realized that I was witnessing the beginning of the end of wisdom as we knew it. Even wisdom had been reduced to mere information.

“…I realized that I was witnessing the beginning of the end of wisdom as we knew it. Even wisdom had been reduced to mere information.”

Increasingly, it is dawning on people that while the first two industrial revolutions that spanned from the 18th century through the early 20th century began the process of replacing the human body, the technological revolutions of the 20th and 21st centuries, sometimes known as the third and fourth industrial revolutions, have begun replacing the human mind.

The 20th century computing revolution introduced sophisticated calculation, machine automation, and the ever-expanding internet. The 21st century has most notably introduced the world to AI, propelling us at warp speed towards a drastically different future.

It seems like every other post, article and conversation these days is about AI. Some futurists caution — while others romanticize — a post-labor economy in which all or most of us will be out of a job. “It will be okay,” they say, since our needs will be provided for by autonomous robots that do everything that was once upon a time called “work.” And whatever cash or bitcoin we will need will be provided by a mythically benevolent government-like entity that will dole out what is known as UBI (universal basic income) happily ever after. But all of this begs the devastating questions of what will we do with our time? And who will we be without our professional identities?

These third and fourth waves of industrial revolutions have washed over us so quickly, and have so successfully distracted us that most of us have yet to appreciate the proportions of what is happening to us faster than we can keep track.

When those Ivy Leaguers reached for the phones after being prompted to think about wisdom, they were embodying what it meant to be raised in the “Information Age.” Memorization and “knowing stuff” were “no longer a thing” — or so we had been told. The promise of emerging technologies was that we could outsource our memory to the cloud so that we could do the “real thinking.” How wrong that hypothesis was.3

What we are living through now should be appreciated for what it is — a massive step towards not thinking at all. Whereas the Information Age was about outsourcing information retrieval and calculation, the Age of AI is about outsourcing thinking, processing, judgement, and decision-making.4

We are being led to believe that real, human intelligence can be completely substituted with artificial intelligence.

As an educator, I want to challenge that foregone conclusion.

“We are being led to believe that real, human intelligence can be completely substituted with artificial intelligence.

“As an educator I want to challenge that foregone conclusion.”

As we’ve seen already in the Language of Life Series, the richest concepts in Jewish consciousness have a full palette of distinct words in Hebrew to reflect distinct experiences in the world. Sharpening each word against the other can give a person a much more clearer view of life. We’ve seen this most notably in our exploration of joy and speech. There are a multitude of words for both because there are a multitude of kinds of happiness and communication. Each word points to a different one.

Our exploration of what constitutes real intelligence should bring us to the definitions of three essential words in Hebrew for the work of the mind. We’ll see how each of them is brought into high contrast through AI, which does not possess any of them:5

khokhma-חכמה

bina-בינה

da’at-דעת

Let’s start with khokhma.

Khokhma-חכמה

In the “Age of Abundance,” the issue is no longer finding what we need. It is about knowing what we need.

“In the ‘Age of Abundance,’ our issue is no longer finding what we need. It is about knowing what we need.”

When I was in elementary school, we spent a considerable amount of time learning the Dewey Decimal System for categorizing and finding books in a library. If you knew what book you were looking for, you would have to hunt it down in a physical library, which may or may not have it, by flipping through musty index cards in a yellowed wooden cabinet system. I’m not sure how people looked for books before 1876, when Melvil Dewey made his system public. There were far fewer books and periodicals in print, but they were even more difficult to locate.

Today, there is a veritable deluge of knowledge.6 About ⅔ of humanity could search virtually the entirety of human knowledge with a device they carry in their pockets (when it’s not in their hands). But having access to information is only a precondition to becoming wise. To become wise, a person must know what they want to know, and want to know it in the first place.

The Zohar sees in the word khokhma-חכמה an acronym for koakh mah-כח מה, the “power of asking ‘what?’” Google and ChatGPT can deliver what we ask for, but only if we ask for it — only if we care to ask “what?” Technology will only make humanity smarter if we continue to educate humans to value and seek out knowledge.

And once we do prompt it with our question, and subsequently get sprayed with the firehose of knowledge that is the internet, we must be wise enough to distinguish between “what is important and what is more important.”7 Receiving a bulleted, bolded, and thoroughly emoji’d list in response to my ChatGPT prompt challenges and highlights what wisdom is. It is ultimately I and only I who must sift through its response, and decide how I digest it.

Khokhma-חכמה is usually translated as “wisdom,” but it’s far more precise to translate it as our receptivity to wisdom. Wisdom is less about the content of the wisdom itself, and more about a person’s curiosity and openness — his willingness and ability to absorb it. Unwise people parroting otherwise wise aphorisms are not considered wise precisely because of the way they mishandle wisdom. Wise people think before they speak, unwise people tend to just speak.

Talmud Bava Metzia 85b:

“…a small coin in an empty barrel rattles loudly.”

Wise people handle wisdom with care because they value wisdom like their life depends on it because it does. This is why the hallmark of a wise person is that he or she “learns from all people,” always thirsty for wisdom, wherever it is found. Wisdom lies in the ascribing value to wisdom, and it is precisely this notion of weight and value that must be trained by humans with real intelligence. This is why artificial intelligence will only ever work with information, but will never replace human wisdom.

“How much we value wisdom is the hallmark of our wisdom.”

The deluge of information we are living through is preparing us for a future beyond our imaginations. In the meantime, whether it is a blessing or a curse depends on our desire and ability to process it.

Stay tuned for an exploration of the two other areas of real intelligence, bina and da’at.

The famous adage of neuroplasticity is that “neurons that fire together, wire together.” Neurons fire together either when one works hard or one is enjoying himself in a state of play.

A “yeshiva” is a school dedicated to the study of Torah.

The book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, by Nicholas Carr (2011) is a little dated, but the principles of learning and the vital role of memory are timeless. His conclusion from the research is that people can only reason fluidly through the information they have readily available in their own minds.

Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything (2012), by Joshua Foer, the co-founder of Sefaria is also a fascinating exploration of why memory will never go away and how to get it back.

Here is a Time magazine article summarizing the findings from a June 2025 MIT study about the dramatically diminished brain usage among users of ChatGPT or other LLMs.

They are very often grouped together by their acronym חב”ד, or spelled in the familiar English shorthand “chabad.”

Chabad, the best known stream of Orthodoxy in the world, adopted the name “Chabad-חב”ד” because of its focus on deep thinking at the core of its practices. “Chabad-חב”ד” is an acronym for Chochma, Bina and Da’at. You can listen here to one of the great intellectuals of the Chabad world Rabbi Immanuel Schochet explain these three in his own words.

An increasingly well-known line in the Zohar understands a verse in the Torah portion about Noah and the Flood to prophetically refer to the “flood” of knowledge that characterizes the modern age. The Zohar very specifically pinpoints the beginning of this deluge of information in the year 1840 CE.

Zohar 2:161a.

In the 600th year of the sixth millennium [5600 according to the Jewish counting, corresponding to 1840CE] the gates of wisdom above together will the wellsprings of wisdom below will open up and the world will prepare to usher in the seventh millennium. This is symbolized by one who begins preparations for ushering in the Sabbath on the afternoon of the sixth day. In the same way, toward the end of the sixth millennium, preparations are made for entering the seventh. The hint for this is “In the 600th year of Noah’s life ... all the wellsprings of the great deep burst forth and the flood gates of the heavens were opened.

A classic line by one of my teachers, Rabbi Noach Orlowek.

Another great substack! Thank you, Rabbi!!

Is it fair to say that AI is skipping ahead to bina and da’at without the ability to possess khokhma?

Hi Rabbi Jack! I appreciate you and your writing.

I’d like to explore the following ideas with you:

There is a kind of wisdom that AI can’t touch- which is the drop of wisdom that God puts into a persons head at just the right time because he wants that flash of insight to be in the world, he wants that person to take a certain action, he wants that soul to complete its mission and transform. We are not brains walking around in a cold world. We are souls with a Mission to do here.

Silicon Valley thinks the world is a gigantic math problem. It’s so much more! And of course that’s why the Torah is multi-layered. We move in thought, speech and action. A thought is one part. Speach and action bring it into the world.

And at the same time, if that action is a mitzvah, there is an additional layer: it’s bringing connection with the divine, drawing something above this world into this world.

Only LaShon HaKodesh can contain the energetic wholeness of any G-dly concept. I touch on this in this talk here - and relate it to what happened at the Tower of Bavel and the Garden of Eden.

Torah is Divine Wisdom so it stands above the strictures of this physical reality. As G-d's wisdom is so far and above our own, whenever ideas are diffused into any other language (eg English), they are only partially whole. G-d recognized the power of language and took this wholeness away from those who wanted to challenge him. Only Lashon HaKodesh can capture the fullness of any idea, and the letters themselves are containers for the spiritual DNA of the concepts they contain (hence, why Adam HaRishon was tasked with naming the animals in the Garden of Eden, essentially meaning, he matched the spiritual DNA demarcated by the letters with the essence of the creatures thereby identifying their true essence).

This may be why it appears that the commentaries contrast each other, when in reality, just as certain Hebrew words can have multiple English definitions, the commentaries which appear to contrast each other, are just getting at different faces of the same truth/idea/reality. The Torah itself is obviously not a "book" in the classical sense. It is more like a painting, a container, into which G-d poured his essence, the into the letters, but also, into the not-letters, and this is also why the Torah operates on multiple levels, black fire on white fire, sound, space, cantillation, language, meaning, visual etc. and helps to explain why the Torah and HaShem are one. This is further elucidated as when the Jews received the Torah at Mount Sinai it suffused all of their senses and why a life of Torah necessitates serving G-d with all of our faculties and senses at once as we become entirely engaged and merged with G-d through doing the Torah and Mitzvoth.

As you mention, all the technology is meant to give us a glimpse into the age of Moschiach, when God will be visible in the world. AI for example shows us what it means to speak and create. Thus we can better appreciate Bereisheit.

Have you seen this shiur by YY Kazen, founder of Chabad.org: https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/2436505/jewish/Introducing-Chabad-Lubavitch-in-Cyberspace.htm