Prayer

how does it work?

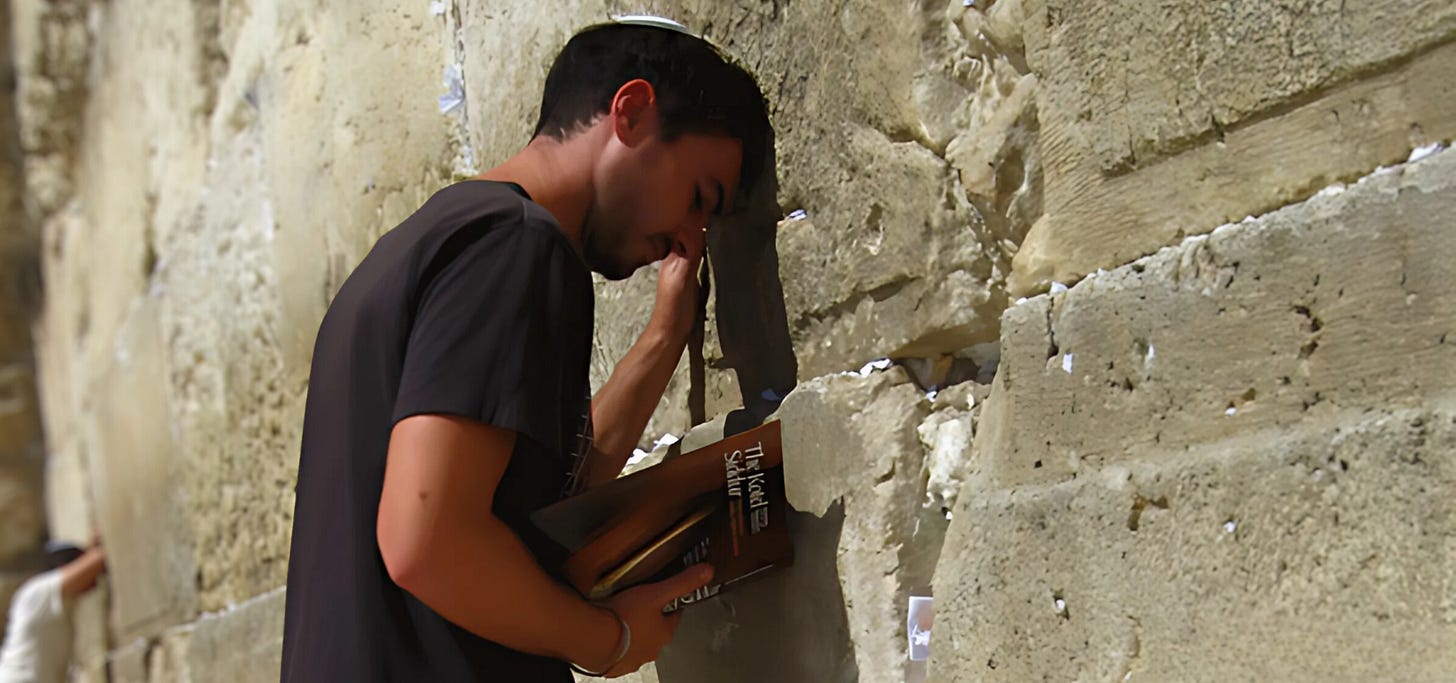

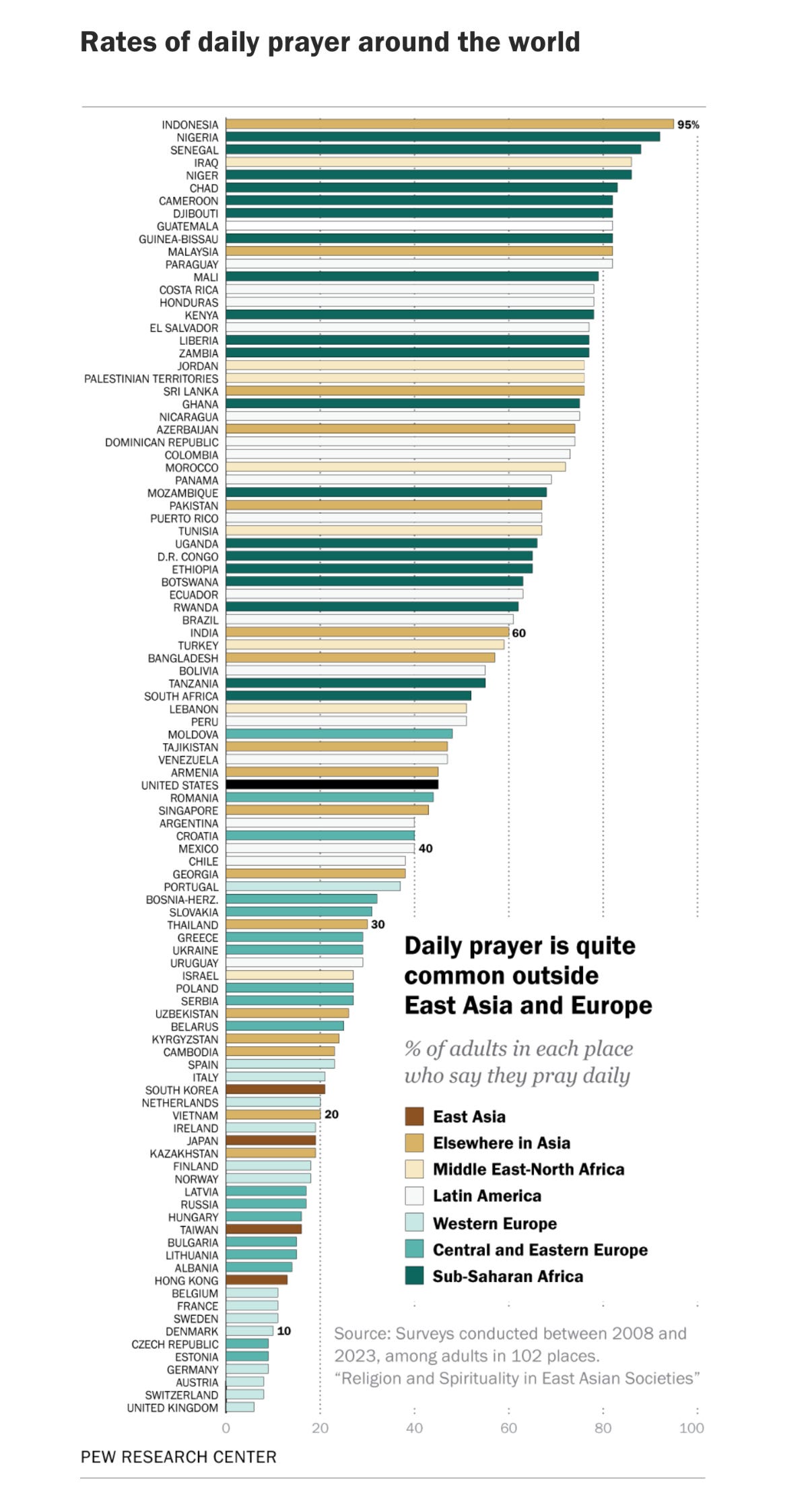

Prayer is the quintessential religious activity. Around the world, about half of those surveyed by Pew responded “yes” when asked if they pray daily.1

Its popularity, though, doesn’t explain how or why prayer should work.

Are we just begging God until He “gives in” to our pestering prayers?

Are we meant to formulate logical arguments to “convince God” to let us have what we’re asking for? Is that what prayer is supposed to be?

Or is it that God, for some reason, is unaware of what we need until we bring it to His attention? Because this would make ZERO theological sense.

These are actually hard questions that would likely stump most people who pray daily.

What is prayer? How does it work?

In Hebrew, “to pray” is L’Hitpalel-להתפלל.

The strange thing about L’Hitpalel is that it’s a reflexive verb. “Reflexive” means that people do it to themselves.2 Let me give you some other examples:

L’Hitlabesh-להתלבש - to get yourself dressed

L’Hitkaleakh-להתקלח - to take a shower

L’Hitgaleakh-להתגלח - to shave

This might surprise you since ostensibly prayer is something you do “to God” — not to yourself.

This may help us answer our original questions because it would mean that praying is not about changing God’s mind, but rather changing my own. But in the meantime, it spurs new questions:

How does talking to God change me? And if I am the one being changed, how does this help me get what I want from God?

Here’s how prayer works and why it all makes perfect sense.

The Hebrew root of מתפלל (Mitpalel) is .פ.ל.ל (P-L-L).

It means “to contemplate a possibility as real.”3

It also has a connotation of judgement because a judge needs to do precisely this: he or she must consider each side as a real possibility, and then judge which of those possibilities is most plausibly real. Doing this successfully requires a sincere desire to arrive at the truth, a robust imagination, and clear thinking, which incidentally are essential for powerful prayer.

Now, when we conjugate .פ.ל.ל (P-L-L) with the reflexive structure, we get התפלל (Hitpalel). Hitpalel means to get myself to consider my own deepest desires — my needs and wants — as real possibilities — even as I try to consciously stand before the objective truth of God’s will.

“Hitpalel-התפלל means to get myself to consider my own deepest desires — my needs and wants — as real possibilities — even as I consciously stand before the objective truth of God’s will.”

Is what I’m asking for reasonable? Do I really need it? Do I really want it? Do I deserve it? Am I doing my part to get it? These are all questions that run through my mind as I turn to God with my requests.

I think back to when I was once again single after my divorce. At some point, during that dark period, I had so given up on the idea of me being happily married that I barely prayed about it. I couldn’t bring myself to utter the words. Or rather, I was afraid to. What if the answer was “no”?

(The story goes that my dear friend’s mother-in-law spontaneously gave me a blessing that opened my mind to the possibility of, in her words, a “grand family,” allowing me once again to ask God for Him to help me make it a reality. I am grateful beyond words for Him continually answering those prayers over the last 11 years!)

God may want something for us — to get married, find a job we thrive in, have kids, get one of our kids into the right school, or married to the right person — but our inability to see it or appreciate it may be the bottleneck that prevents it from happening. Why would He provide it before we’re prepared to accept it?

To truly be open to life’s most wonderful possibilities, we need to first see them as possible and believe that the One Who runs the universe wants them for us.

We must:

Be so fully aware of Hashem’s existence that we actually feel ourselves in His Presence.

Believe that He wants what is best for us and no obstacle is stopping Him from bringing it about.

Feel deserving of receiving it.

The work of Tefila-תפילה (prayer) is reflexive because we are changing our own minds. To th degree to which we succeed in doing so, God will provide us the good He so wishes to give us.

Here’s a breakdown by Pew, if you’re interested of the rates of daily prayer by country. Note that white Americans in “blue states” tend to underestimate how religious their country is.

Hebrew has different “constructs” that modify how the verb works.

The simple construct of Lovesh-לובש simply means “wears [clothing].”

By modifying the construct to causative, I can change the same root letters to mean “to dress [someone else]” — He’halbish-להלביש.

The passive construct would Nilbash-נילבש, “worn.”

The reflexive “to dress oneself” would be L’Hitlabesh-להתלבש.

Yaakov (Jacob) suffered for more than two decades thinking that his son Yosef (Joseph) was dead without conclusive evidence. Reflecting on that period, Yaakov remarked to his son:

Bereishit 48:11:

“I did not imagine that I would ever see your face again, and here God has shown me even your children — ראה פניך לא פללתי והנה הראה אותי אלקים גם את זרעך.”

Rashi explained the verb פלל evocatively as “my mind was not sufficiently filled to consider the thought that I would see your face.”

Thank you for expanding my perspective on prayer. I never thought about my role in the process of prayer in that way, and it adds to the idea of being “partners in creation” with God. I also appreciate your honesty in identifying the fear that the answer might be “no”.

I wonder if you have any thoughts on how to use?rhe shemonei esrei for this reflective work?