Kingship

in contrast to dictatorship

According to Kabbalah, the inner wisdom of the Torah, the final week before the holiday of Shavuot (which begins this Sunday night) is saturated with an energy of royalty, nobility and leadership.1

Maybe it’s just me, but the word “leadership” has become woefully trite in modern times. Just about everything seems to be about “inspiring future leaders,” “networking with other leaders,” and “bringing out your leadership potential.”

In a culture of corporate climbing-to-the-top, the image of leadership tends to be exclusively drawn as a rigid, determined figure at a podium, boldly addressing a crowd of thousands. While there is, of course, a place for this sort of leadership-from-the-front, it is, no doubt, only one kind of the many sorts of leadership which our communities and our world at large need.

We should invest in future leaders, but pushing for only this narrow archetype will leave us perpetually searching for the guidance and unity we so desperately seek.

There are many words in the Holy language for leadership (as we saw that there are for happiness) each one refracting a different nuance in what leadership is about. However, the word that most encompasses the essence of leadership is malkhut-מלכות, “kingship.”

Most of us have only mythical conceptions of what a king or queen are. Even those of you reading XL in the British Commonwealth know only figureheads paid by the state to preserve a nearly forgotten notion of royalty.

On the other hand, those individuals today who exercise great power over their people, like Kim Jong Un, Khamenei, Putin and others — are dictators, not kings.

In the Hebrew language, there is a clear distinction between a moshel-מושל and a melekh-מלך.

A moshel is essentially a tyrant, who rules unilaterally because he can. The tyrant wields a monopoly on power and uses it to control the state.

In contrast, a melekh rules in the interest of the people, and with the people’s consent.2

It is for this reason that the same root .מ.ל.ך is used to mean “to seek counsel.”3 In other words, a true king or queen — a true leader — rules not simply through an exercise of their own power, but is empowered to lead through the trust of the people, who seek their counsel.

“…a true king or queen — a true leader — rules not simply through an exercise of their own power, but empowered to lead through the trust of the people, who seek their counsel.”

Understanding this distinction helps us grasp the pushback of Joseph’s brothers to Joseph’s heavy-handed speeches about his prophetic visions of leading the family, in which his brothers would be subservient to him:

Bereishit 37:8

וַיֹּאמְרוּ לוֹ אֶחָיו הֲמָלֹךְ תִּמְלֹךְ עָלֵינוּ אִם־מָשׁוֹל תִּמְשֹׁל בָּנוּ וַיּוֹסִפוּ עוֹד שְׂנֹא אֹתוֹ עַל־חֲלֹמֹתָיו וְעַל־דְּבָרָיו׃

His brothers answered, “Do you [really think] that you will successfully reign over us (as a melekh-מלך) by insisting on imposing your rule over us (as a moshel-מושל)?” And they hated him even more for his dreams and for his talk [about them].

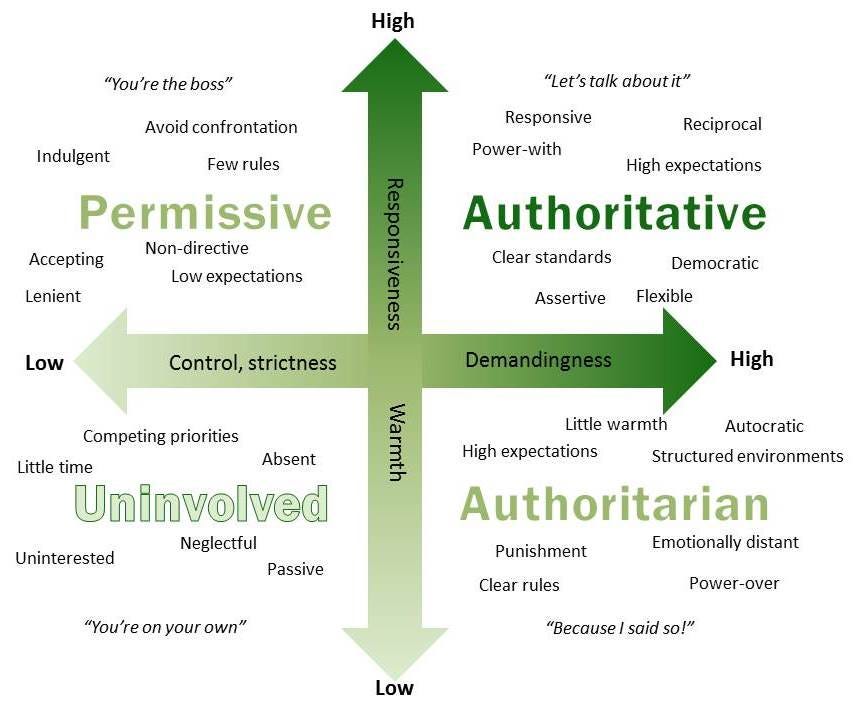

These two concepts of leadership are analogous to the research by psychologist Diana Baumrind in the 1960s that created a schema of 3 different parenting styles: 1) permissive, 2) authoritarian, 3) authoritative, (and a fourth type of non-parenting called “uninvolved parenting”).

“Permissive” parenting refers to parents who permit their kids to do whatever they want — a sort of populist-anarchy.

“Authoritarian” parenting is a “Because I Said So!” Dictatorship — governance with an iron fist as a moshel-מושל.

Finally, “authoritative” parenting is through a bond of trust of a melekh (king) and his malkhut (kingdom). The child trusts the counsel of the parent, and learns to listen not because his parents raises their voice, or threaten punishments, but because what they say has proven to be loving and wise guidance time and time again. This typology has been studied and applied since Baumrind’s research on parenting, across the board, from business management to teaching to sports coaching.

True leadership is not getting people to do what we want.

True leadership is cultivated through the development of trust, which, in turn, is developed through guidance that is consistently given in a way that is proven to be helpful to those being led.

This is the malkhut-מלכות — the leadership we seek for ourselves — and the leadership we should strive to embody towards those who look to us for much-needed guidance.

The 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot are broken down into 7 weeks, in which each week is dominated by an essential energy (Lovingkindness, Strength, Balance, Resilience, Admittance, Bonding, and Kingship), and everyday an aspect of that larger theme.

A thought-provoking insight by Rebbi Nachman of Breslov teaches that these energies are so woven into the fabric of human life that “everything which everyone in the whole world is talking about is purely an expression of the particular aspect with which that day is associated. A person with understanding can hear and recognize this if he pays attention to what people are saying.”

Interestingly, aside from being the anniversary of the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai, Shavuot is also understood to be the birthday and anniversary of the passing of King David.

Very similar to the more general concept of the “social contract” developed by Enlightenment political philosophers.

See Nehemiah 5:7.