Intention

Kavana as Alignment

theexpressionoflife.com is evolving…

I can’t tell you yet too much about what’s in store, but I will tell you that I’m excited.

The future of XL is more interactive, more interconnected, and more dynamic. Our vision is much deeper and broader than an newsletter…

A few weeks ago, we began to explore what prayer is by carefully studying the Hebrew word for it, mitpalel-מתפלל.

This week, I want to think together about the most essential mental maneuver to be able to pray — what’s known in Hebrew as kavana-כוונה.

Kavana is normally thought of as “concentration,” and is most often translated as “intent.” While these are reasonable English language associations with the Hebrew word kavana, they miss its core meaning, and may not help you actually figure out what it is you’re supposed to do when you decide to concentrate.

“Concentration” conjures up an image of a person physically exerting himself, trying with all his might to get himself to think intensely.

In my experience, this approach to mental focus ironically makes it harder to concentrate. I personally end up getting distracted by the physical strain in my face and body, as well as by the focus on “trying to focus” — instead of what I want to be focusing on.

The word “intent” is better. The problem with it is that it gives to indication as to how to live and pray with more intentionality. After all, we may intend to have a meaningful prayer session, but fail dismally despite our best intentions.

What secrets are encoded in the word kavana-כוונה that can guide us to actually putting it into practice?

Kavana-כוונה is the verb form of kivun-כיוון, which means direction.

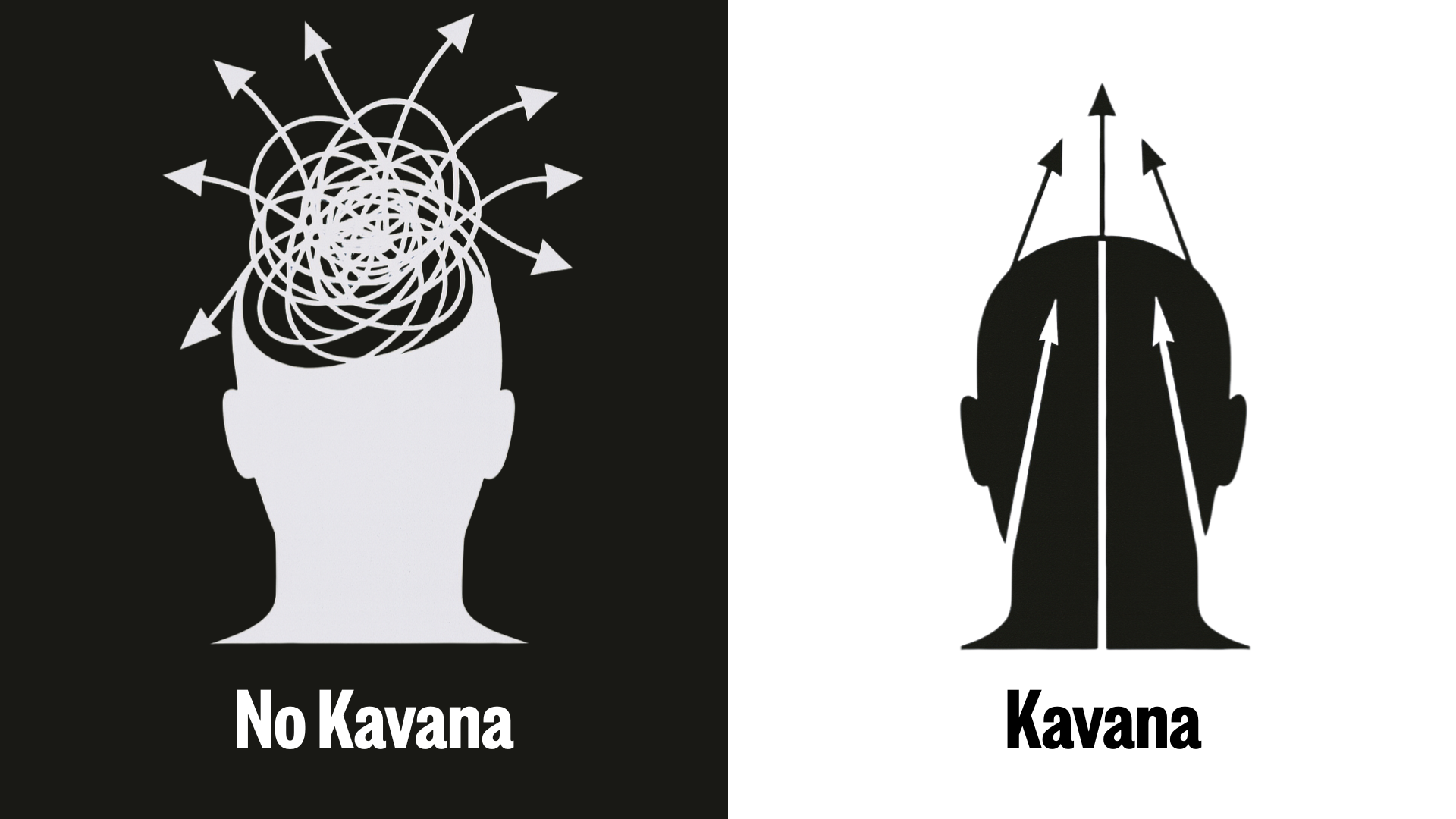

To have kavana is to direct, aim and align your mind, heart and body. It’s this alignment that allows our intentions to flow through us — and it’s this flow that is the essence of prayer.

“To have kavana is to direct, aim and align your mind, heart and body.

It’s this alignment that allows our intentions to flow through us — and it’s this flow that is the essence of prayer. ”

The problem is that the mind’s natural state is s c a t t e r e d.

If this isn’t immediately evident to you, try to be quiet for two minutes, and watch your thoughts bounce from one thing to another.

“Am I doing this right?”

“Has it been two minutes?”

“My nose itches.”

“Oh man I forgot to call Steve back!”

Because our attention is loosely attached to whatever happens to be scrolling through our minds at any given moment, we tend not to realize how random our thinking is. We just follow the bouncing ball of our thoughts.

Manually scrolling through social media just masks our inattention. It does this through an illusion of focus on whatever the algorithm feeds our bottomless appetite for distraction.

While those with diagnosable ADHD certainly experience a significantly larger deficit of attention relative to most people, most people suffer from an objective deficit of sustained attention on what we truly want from life — and suffer we do from the consequent misalignment.1

Spiritual disciplines over the millennia have had to reckon with the problem of our perpetual distraction. It’s a hard fact of the human condition. Any discipline that ignores or avoids this fact is naive and not a discipline at all. And it’s not just because of smartphones and micro-form video content (although these certainly haven’t helped).

The Buddha was teaching people how to calm and direct their minds 2,500 years ago, and Hinduism was already addressing the issue even prior to the Buddha. Both traditions often refer to the dilemma of the “Monkey Mind.”2

Although the discipline of meditation was prominent in Judaism in ancient times, and was revived more recently in pockets of the Mussar tradition, some Chassidic schools, and the Sephardic Kabbalistic system of the Rashash — the meditative tools of Judaism remain essentially invisible to the general population today.3

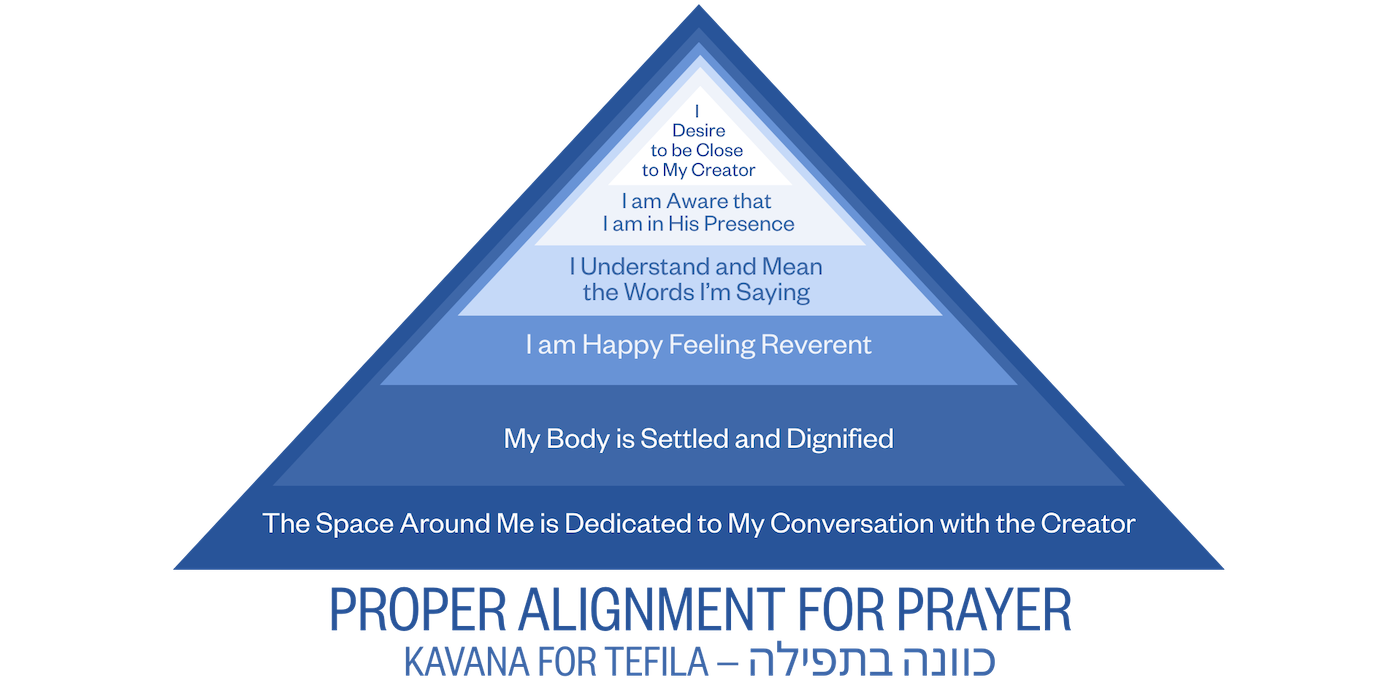

Let’s look at kavana as a mindfulness practice of alignment more closely and practically:

The Talmud, 1,500 years ago, identified a number of verses in Tanakh, written millennia prior, as speaking to the need to align one’s mind, heart and body — not just before uttering words in prayer, but also before performance of a mitzvah.

It should be noted that even this oft-used English word associated with mitzvot — “performance” — is precisely what the sages of the Talmud wanted us to avoid. Mitzvot and certainly tefila (prayer) are meant to be profound experiences of connection and relationship with God. In order for them to indeed be connection points, not merely “performances,” we have to first align the many layers of who we are towards the goal of connection.

This is precisely the function of saying a beracha before a mitzvah, and the goal of the entire lead-up to the amida in prayer — inner and outer alignment.4

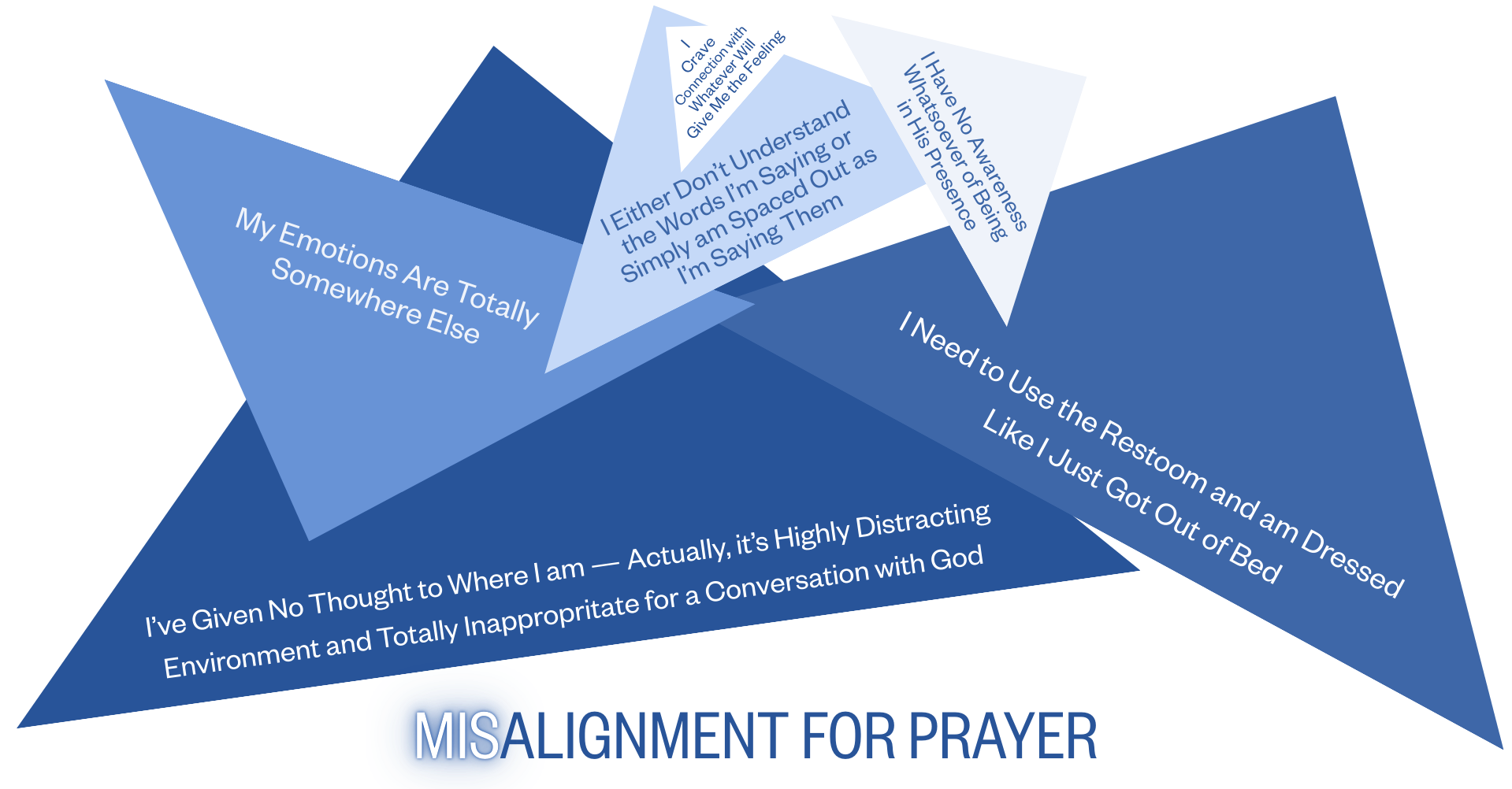

Here’s a visual of what alignment might look like:

Our first flicker of awareness should be trained towards gratitude towards the One Who has given us another day of life.

As mundane as it sounds, we have to make sure we use the bathroom so that our bodies are clean, healthy and undistracted. We wash our hands to be physically clean, but also to shed the sleepy unconsciousness from them.

We get dressed in a way that doesn’t produce a mismatch between how we look and the momentous meeting with God we are hoping to have.

Since our emotions do not autonomously blossom when we open up a siddur (prayerbook), we have to warm them up to align with the encounter with our Creator. After some discussion, the Talmud concludes that the appropriate emotional state for prayer is a joyful reverence (or a reverent joy). By considering how precious the opportunity is to have quality, mindful time of connection, we are meant to feel great about having achieved a state of true trepidation.

This emotional state is reached through a conscious state of awareness that we are “before God.” Meaning, although we cannot visualize God, we can visualize ourselves before Him. We can consider that our actions, words, and even thoughts are all seen by Him. This “being seen” is what all of our souls desire, and naturally brings joy.

We then focus on aligning the words we say with this consciousness. To mean what we say we need to: a) understand at least their simple meaning, and then b) actually mean them sincerely.

The desire that is meant to course through this alignment is the sincere desire to connect with our Creator. If this sounds foreign, think about it as simply the desire to connect — the desire to be aligned with your purpose — the desire for meaningful moments. All humans desire this. We just need to calm our minds enough to allow this desire to shine through.

This alignment isn’t necessarily a specific step-by-step process. Different people on different days may have to focus more on one element than another, but the idea is that a powerful spiritually experience of connection depends on this alignment — on our kavana.

The alternative is the default, mindless state of misalignment.

Without intentional alignment, we are all scattered. We barely know where we are, and have given no thought as to where we want to be. We might be dressed like we just rolled out of bed, and haven’t even stopped to take care of our bodily needs. Our emotional state is blowing in the wind. We open the siddur and mumble words out of habit, often not even noticing that they don’t register meaningfully in our minds.

Without doing the work of alignment, we obviously have no awareness of being in God’s presence, and our conscious craving is for breakfast and/or sleep — not to connect with our Creator.

Alignment is a choice.

Perhaps the most important choice we can make everyday.

It’s all in the word kavana-כוונה. Another example of how the “language of life” can guide us.

Next time, we’ll take a look at the word for prayerbook, siddur-סידור.

I recently discovered this powerful, eye-opening website that seeks to simulate for people without ADHD the lived experience of ADHD.

Here’s another excellent video by Headspace that gives helpful tool for how to begin to train one’s monkey mind:

The exact same technique is found in the writings of the Piaseczno rebbe, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira. You can find it in the original Hebrew here.

The introduction to Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s book Meditation and Kabbalah has a wondeful overview of meditation in Jewish tradition, and his more simplified, practical work Jewish Meditation is a powerful guide for exercises you can try on your own.

The Ritva in Pesachim says this explicitly (exact source needed).

Mid