Independence

and the fortified bones of identity

I’ve decided to switch gears for a bit in our Language of Life series to compose shorter, more to-the-point posts about individual words that come up frequently in Jewish practice but aren’t well understood. My aim here is to chip away more practically at the problem of illiterate literacy, which I raised at the beginning of the series.

I’d love your feedback in the comments below.

Last night, as soon as Israel’s Memorial Day-Yom Hazikaron came to an end, Israel’s Independence Day-Yom Haatzmaut began.

The notion of making a country’s memorial day lead straight into its independence day is brilliant, and as far as I know, unique to Israel. We cannot celebrate on Yom Haatzmaut without appreciating on Yom Hazikaron the price we’ve paid. It’s incumbent on all of us to mourn the loss of 25,420 Israeli soldiers and civilians, whose lives were sacrificed to allow us “to become a free nation in our land, the Land of Zion and Jerusalem.”1

This year, Yom Haatzmaut celebrations in Israel have been officially canceled due to the fires ignited by Palestinian arsonists who clearly have no respect for human life or the land they live on.

I’ve seen a few people who have already pointed out that the haze of smoke clouding the Israeli air is an evocative metaphor for the currently hazy future of our still young country.2 This haziness is not only due to external threats that continue to exist after more than a year and half of war. It also stems from internal conflict and a palpable vulnerability, which our enemies seek to capitalize on.3

At the same time, Israel’s apparent inability to pull the trigger necessary to disarm an Iranian regime that openly intends to destroy it, waiting for the green light from the Trump administration, begs the question:

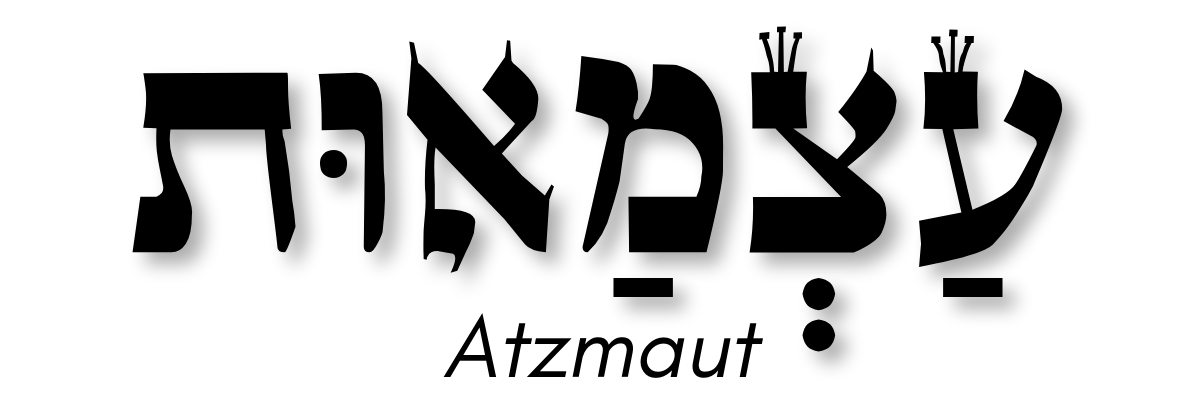

As we celebrate Israeli Independence (עצמאות), are we truly independent (עצמאים)?

Which in turn, moves me to ask:

What is the true meaning of Atzmaut-עצמאות?

It turns out that the Hebrew term “Atzmaut” was coined only in the 20th century by the journalist Itamar ben Avi, son of the reviver of Modern Hebrew Eliezer ben Yehuda, and as a result, the first native Hebrew speaker in modern times.4 Like most modern Hebrew words, its roots can be found in Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible) and rabbinic literature (Mishnah and Gemara).

The first usage of the Hebrew root .ע.צ.מ is etzem-עֶצֶם, which means “bone.”5

The next usage is atzum-עצום, meaning “strong.”6 (As a noun, “strength” would be Otzmah-עוצמה.)

What’s the difference between “Otzmah” and the more common words for strength, “Koach” or “Gevurah?”

“Koach” refers to the power or potential to do something difficult. “Gevurah” refers to the ability to overcome an opposing force. “Otzmah” would be best translated as fortitude — the resilience to withstand pressure.7 It’s clearly a related concept to that of the bones that give our otherwise soft skin and organ tissue strength and structure.

In rabbinic writings, the word Atzmi-עצמי means “myself,” conceptualizing one’s essential self as the sort of internal skeletal essence of a person.8

More generally, the word Etzem-עצם is commonly used to refer to the essence of a thing.

The connections between these words is not happenstance. The strength of a person or a people depends on how clear and true they are to their inner identity. The fortitude of our spiritual bones is what allows us to stand tall in the face of adversity — to do what’s right because it’s right — to be ourselves because we can be no one else.

“The fortitude of our spiritual bones is what allows us to stand tall in the face of adversity — to do what’s right because it’s right — to be ourselves because we can be no one else.”

True independence — עצמאות — is deeper than just declaring independence. We must have the fortitude that stands the test of time against the external and internal pressures that seek to shape us.

Our full independence is yet to come.

Until then, Yom Haatzmaut Sameach — יום העצמאות שמח.

A translation of the last line of Hatikvah, Israel’s national anthem. I see no reason why we shouldn’t all take this time to mourn those who have sacrificed themselves even if we aspire to more than merely a “free nation our land — עם חפשי בארצינו.“

The Talmud says that the air of Israel is meant to "make [us] wiser.” Today, it’s making us especially aware of how blurry the future is.

I found this interview with Ari Shavit clarifying amidst the haze of the polical tensions in Israel now epitomized by the conflict between Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and outgoing head of the Israel Secret Agency Ronen Bar.

"Here I see in my imagination the 'end of days' [the Messianic times]…Here our brothers are being gathered and coming from all their dispersions to the land of our forefathers… Here the G-d of our ancestors sends before us the will and the strength to establish upon their foundation Hebrew independence (עצמאות) in all its splendor” (recorded in Ben Avi’s autobiography).

When the first woman (Isha) was created from the first man (Ish), as we’ve discussed at length in previous posts, the man exclaimed upon seeing her that he was amazed and grateful that she was “bone of my bones (עֶצֶם מֵעֲצָמַי) and flesh of my flesh.” She was made of the same stuff.

When the Children of Israel multiply in Egypt, the Torah describes that them as “multiplying,” “teeming,” “being fruitful” and “becoming very very strong (וַיַּעַצְמוּ בִּמְאֹד מְאֹד).”

See the Malbim on Yishaya.

As in the well-known line from Hillel:

Pirkei Avot 1:14

?הוּא הָיָה אוֹמֵר, אִם אֵין אֲנִי לִי, מִי לִי. וּכְשֶׁאֲנִי לְעַצְמִי, מָה אֲנִי. וְאִם לֹא עַכְשָׁיו, אֵימָתָי:

He [also] used to say: If I am not for myself, who is for me? But if I am for my own self [only], what am I? And if not now, when?

Thank you for posting this!