Head of the Year

The meaning of Rosh Ha'Shana

I’ve been doing daily videos about positive practices for healthier communication in a 40 Day Campaign named “Lashon TOV” by my wife, for the health and recovery of my father-in-law Roberto Reuven ben Rachel.

Join the Whatsapp Group or follow on Instagram to get the videos (I’ll eventually post them on YouTube when I have a chance).

You take either some fish head or meat from the head of a lamb, and before you eat it, you pray “נהיה לראש ולא לזנב — we should be a head (rōsh), and not a tail.”1

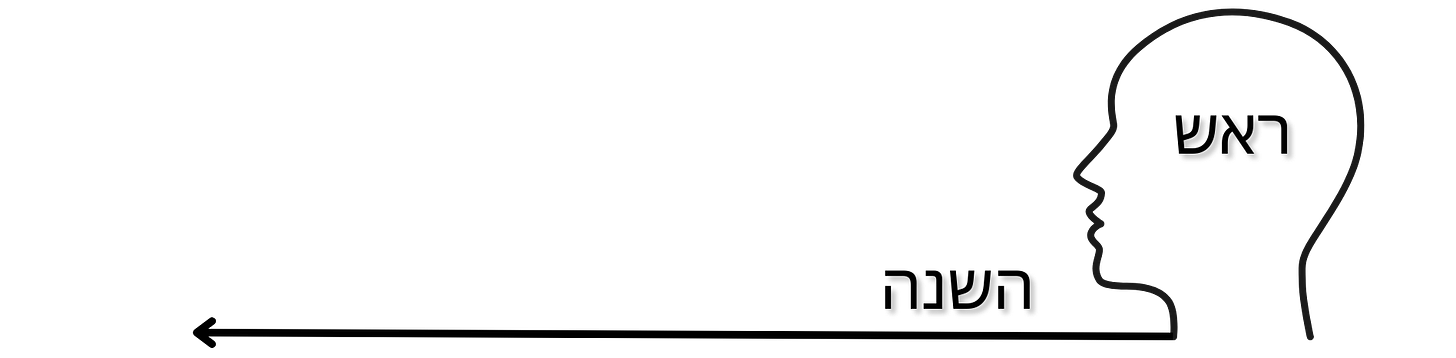

It makes you wonder if the name for the Jewish New Year “Rosh Hashana,” literally, “the Head of the Year” is intentional or just a trivial quirk of the Hebrew language.

Why isn’t it called “Hatchalat Hashana — התחלת השנה,” which would translate to “the beginning of the year”?

Or, as we do in English, “Shana Chadasha — שנה חדשה,” “the new year”?

The Jewish concept of Rosh Hashana is very different than the secular concept of New Year. On December 31, people around the world watch their clocks with great excitement as they approach 12am, eventually counting down from 10 — 9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1, bursting in catharsis, releasing confetti, chugging champagne, and kissing the closest person to them. The year changes, but unsurprisingly, this ritual doesn’t lead to people changing.

Instead, the cycle continues. After all, from a scientific point of view, there’s absolutely nothing special about 12:00am on January 1st. Astronomically, nothing — literally nothing — happens at that moment. The Earth keeps sliding along its elliptical orbit.

In order for our lives to change in a meaningful way, we have to change our minds. We need a new outlook. A new perspective. A new way of seeing, and a new language to talk about it.

“In order for our lives to change in a meaningful way, we have to change our minds.

This is the change we look to make on Rosh Ha’Shana. We don’t just want our feet to keep moving mindlessly in the direction we’ve been walking all year. We want to start the year with perspective, with our head on our shoulders. With a fresh Rosh-ראש.

This brings us to another Hebrew word that perhaps we haven’t given much thought to: Shana-שנה, “year.” What is its deeper meaning?

On the one hand, the verb lishnot-לשנות means “to repeat,” from the word shnayim-שנים, “two.” On the other hand, the word shoneh-שונה means “different.”

Aren’t “repeat” and “different” opposites?

They are, but they come together in the English word iteration. To iterate is to repeat a cycle but with a conscientious modification every time.

“To iterate is to repeat a cycle but with a conscientious modification every time.”

Herein is the misnomer of “10,000 hours of practice” to become an expert, popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers, based on research by K. Anders Ericsson. The misconception was founded on the notion that if you repeat an activity for 10,000 hours, you automatically become an expert. This is patently false. The world is full of bad doctors, lawyers, plumbers, and teachers who have practiced their craft for well over 10,000 hours — and did it wrong every single time. It’s for this reason that Ericsson made sure to call it 10,000 hours of “deliberate practice.” It isn’t the repetition alone that makes one improve. It’s the mindful learning with every repetition, that makes the person 1% better than the time before. This is iteration, and the idea of a Rosh Hashana — mindful iteration.

Before we restart the cycle again, another lap around the sun, we need to feel the existential judgment that asks us if we’re running in circles or becoming better.

May we experience the mind expansion of Rosh Hashana that allows us to see higher than the patterns we tend to mindlessly travel along. May the judgment be sweetened in knowing that the changes we have to make are the changes of growth, improvement, and self-actualization.

Shana Tova!

In case you’re vegetarian, or just plain grossed out, have no fear. You can simply look at the fish or lamb head — or, if you prefer, use animal crackers, and just bite off their heads. To better understand this evocative Jewish practice on Rosh Hashana, take a look at my friend and guest writer Rabbi Moshe Gersht’s article on our site from last year, titled after his most recent book, “The Three Conditions.”

I like this: “The world is full of bad doctors, lawyers, plumbers, and teachers who have practiced their craft for well over 10,000 hours — and did it wrong every single time. It’s for this reason that Ericsson made sure to call it 10,000 hours of “deliberate practice.” It isn’t the repetition alone that makes one improve. It’s the mindful learning with every repetition, that makes the person 1% better than the time before. This is iteration, and the idea of a Rosh Hashana — mindful iteration.”