Defining Decisions

Is free will worth the trouble?

When I was in rabbinical school in Jerusalem, I shared a desk with a young, dark, Israeli guy named Yehezkel with a beaming smile and a fiery learning style, who was barely a yarmulka taller than five feet. He would listen intensely and intently to his chavruta (study partner) while stroking his beard, and then launch passionately and confidently into his own perspective on how to understand the piece of Talmud in front of them.

I liked him a lot, and we became very friendly over the course of the year that we sat next to one another.

One day, he discreetly opened up to me about a problem he had, and asked me for any help I could offer. He shared with me that he suffered immensely from a very particular form of social anxiety. It was preventing him from getting up to go to the bathroom during the three and a half hour block of study time due to an unshakable feeling that all eyes were on him as he made his way to the facilities. For some reason, which he failed to be able to explain to me, he found other people knowing about his bathroom patterns to be mortifying. He told me that no one knew about this issue he had — not his wife, not his parents — no one.

He was desperate.

I tried my best to help him. I’d regularly talk through his thought process with him, and gently suggest therapy. From time to time, I’d create diversions in the study hall so that he wouldn’t feel that people were paying particular attention to him and his digestive rhythms. It broke my heart that he was going through such a painful and private ordeal.

It happened to be that at that time, I was going through my own ordeal with my imminent separation and divorce, which I also didn’t feel comfortable talking about with very many people.

My friendship with Yehezkel wasn’t symmetrical. He would share about his stuff with me, but I didn’t feel comfortable telling him about what I was going through at the time. Every so often, I would share bits and pieces with my own study partner to explain why I was running late, or why I may have looked a bit “out of it” that day, but at the end of the day, it was my own private life-challenge between me and God, just as, no doubt, Yehezkel went home to his own private life-challenge as well.

It turns out that everyone has their own private life-challenges between them and God.

It’s a universal part of life.

The question is: why does God give us these battles?

If you recall, a couple of XLs ago, we explored why an Infinite Being (God) would make a finite universe with us in it.

To explain this huge idea, we introduced the Talmud’s iconic image of the letter Gimmel-ג running towards the Dalet-ד.

True giving is selfless. As such, the giver (“gomel-גומל” in Hebrew) doesn’t have to wait to until he unintentionally bumps into a needy recipient (“dal”-דל in Hebrew) in order to give to him. He doesn’t have to get his heartstrings pulled in order to reach into his pocket and give.

Instead, a genuine, self-driven, giver proactively runs after those recipients and finds them wherever they may be.

It is for this reason that the Gimmel runs after the Dalet to give to him.

What would be the ultimate form of this? An Infinite Being Who doesn’t merely run after people to give to, but goes so far as to create people in the first place in order to give them the gift of all gifts — the gift of life.

This, so far, is review from a few weeks ago.

Now, there’s a twist.

Not satisfied with superficial symbology, the Talmud proceeds to ask a follow-up question:

Why does the back of the Dalet (the top of the ד that sticks out to the right) extend towards the Gimmel?

It answers:

So that [the needy party, the Dal] makes himself available to the [one trying to help him i.e. the Gomel].

But this still begs the question:

And why, then, is does Dalet’s face (the longer horizontal part of the ד on the left) look away from the Gimmel?

Here’s the Talmud’s answer — a profound insight into human psychology:

So that the [giver] gives to him in such a way that does not embarrass him.

Since the Divine essence of a human being is to give of himself, human nature is to feel some shame in receiving a handout from another.

This is why the Dalet is turned away from the Gimmel.

A poor person who can shamelessly look another person in the eyes and demand charity has lost more than his livelihood. He’s lost his dignity.

It’s for this reason, according to the philosopher-mystic Rav Moshe Chayim Luzzatto, that God gave us free will — so that we can feel good about the good that we’ve done.

God want us to be good by doing good, and He wants us to feel good about it.

If He would have programmed us to be good, we’d be good, but feel sort of bad about it.

Remember when you were a kid and your mom would tell you to “say thanks” after someone gave you a gift? Remember how upsetting it would be when you were moments away of saying “thank you” on your own volition when she decided to rob you of the dignity of saying it yourself?

That’s what it would feel like to not have free will. You could have the greatest life, but feel miserable about it.

This is, by the way, the source of the woke complex with “privilege.” If you were born rich and white-passing, you should feel bad about yourself, shouldn’t you?

The answer is not necessarily.

If you’ve received blessings and don’t do anything valuable for the world with them, then, yes, you will naturally feel guilt and ashamed. But if you do good with the good you were given, you should feel good about it!

One could still ask: why couldn’t God just make human psychology different? He could simply make us feel great for doing good — even when we didn’t have a choice to do otherwise?

This is a fair question.

For this you need a deeper answer:

For you to truly be good, it is YOU and YOU ALONE who must be responsible for your goodness.

In a very profound sense, one who lives an easy life — a person who doesn’t make any real choices, but rather allows others to choose for him — this person doesn’t truly exist in any real way. He is a mere projection of the choices of others.

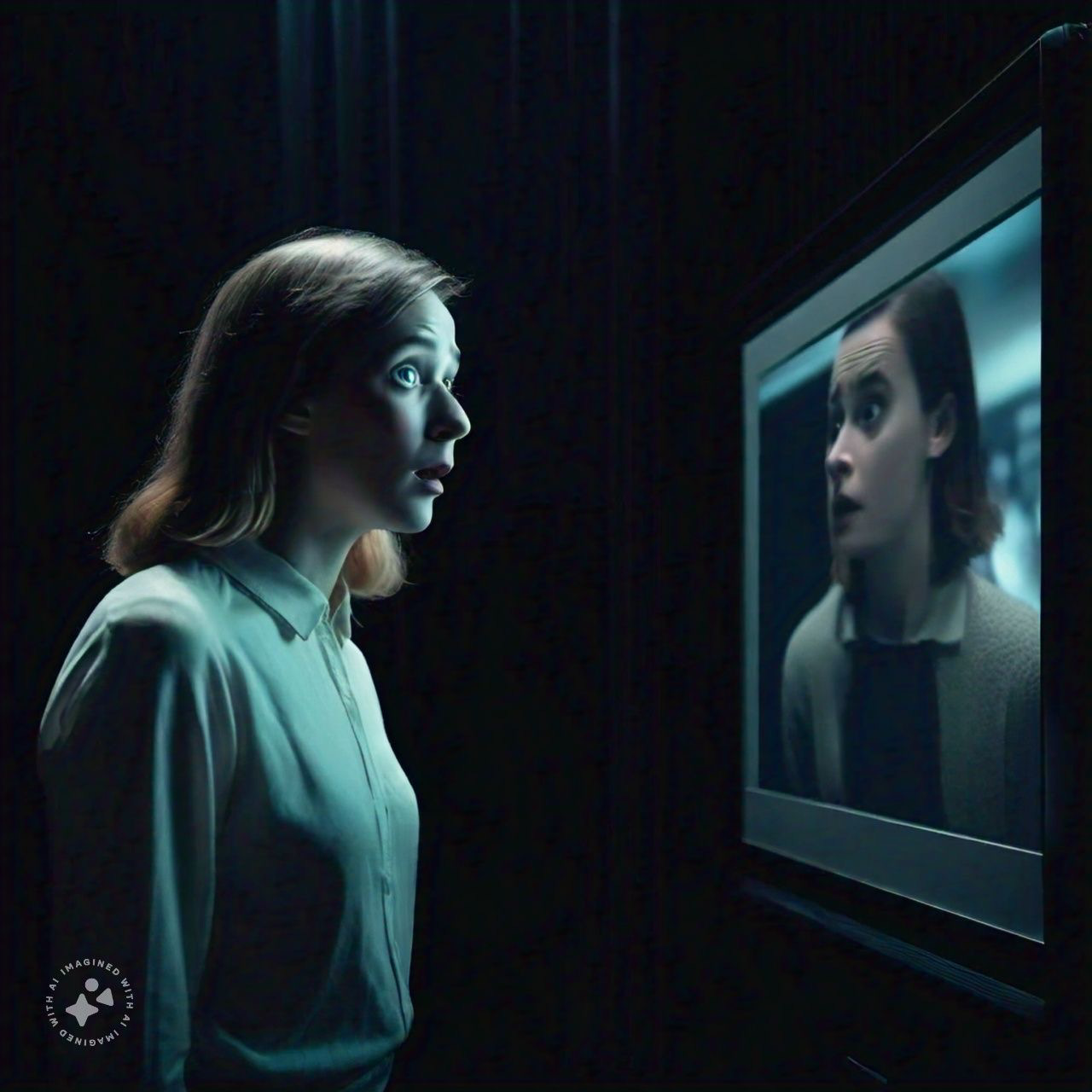

Imagine the deep pain you would feel if you discovered that everything you ever thought, said or did had been scripted by someone else.

It would be the discovery that you never really existed in the first place. You’re someone else’s character, reading someone else’s lines, following someone else’s script.

In this sense, every choice we make in our lives swimming against the current of the life-challenges we face is nothing less than the choice to be1.

To be or not to be — this is the question of our lives — perhaps even more deeply than Shakespeare had in mind.

Our existence is forged in the crucible of our challenges.

But alas, thinking this through has left with more questions than we started with…

No doubt, one of these questions is:

What is free will exactly? Are all of our decisions truly free?

The Choice to Be is the title of an amazing book by Rabbi Jeremy Kagan, which I highly recommend.