Admission

and Gratitude

Have you ever had the experience of repeating a word to the point that it starts to sound almost unrecognizably foreign?

This apparently universal phenomenon actually has a name. It’s called “semantic satiation.”1 The jury is out as to why exactly this happens, but the effect is clear. A word normally full of meaning can decay through repetition into mere noise.

Saying “thank you,” “thanks,” and “thank you so much,” as well as texting “ty,” “thx,” and “tysm” are ubiquitous in our generally polite society, and yet, as these words fly out of our mouths and off our thumbs, they seldom emerge from a profound inner sense of gratitude.

One of the core teachings of Jewish character development (mussar) is that the simplest, most seemingly obvious concepts are the ones we tend to understand the least — precisely because we assume we know everything there is to know about them. Ironically, the most meaningful concepts — like gratitude — are at the greatest risk of becoming meaningless.

Here’s where learning Hebrew as a second language can help. Hebrew self-identifies as a laser-cut language of Divine origin whose words encode the inner meaning of life itself. Precisely because it’s not our native language, we can better use it to gain perspective on concepts we likely feel are simple and straightforward, and in so doing reclaim our thank you’s.

The word for “thank you” in Hebrew is todah (תודה). The common “thank you very much” is todah rabbah (תודה רבה).

The first thanksgiving ceremony in American history was two years prior to the more famous meal of the Pilgrims upon landing on Plymouth Rock. On December 4, 1619, Captain John Woodlief arrived with 36 English settlers on the shores of America, not far from Jamestown, Virginia. It is recorded that the first thing he did upon arriving is kneel, pray, and subsequently declare:

“We ordain that this day of our ship’s arrival at the place assigned for [a] plantation in the land of Virginia shall be yearly and perpetually kept holy as a day of thanksgiving to Almighty God.”

It wasn’t Woodlief though who coined the word “thanksgiving.” That juicy English word can be traced to the first complete (Christian) English translation of the Bible, where it appears a handful of times in the Psalms attributed to King David.

Tehillim 100:

מִזְמוֹר לְתוֹדָה הָרִיעוּ לַה׳ כׇּל־הָאָרֶץ: עִבְדוּ אֶת־ה׳ בְּשִׂמְחָה בֹּאוּ לְפָנָיו בִּרְנָנָה…בֹּאוּ שְׁעָרָיו בְּתוֹדָה חֲצֵרֹתָיו בִּתְהִלָּה הוֹדוּ־לוֹ בָּרְכוּ שְׁמוֹ׃

A song of thanksgiving: Make a joyful noise unto Hashem, all ye lands. Serve Hashem with gladness: come before His Presence with celebration…Enter through His gates with thanksgiving, and into His courts with praise. Give thanks to Him, and bless His name.

Although the American celebrations of Thanksgiving, Black Friday and Cyber Monday have all passed, Jews can be thankful that thanksgiving for us is never more than 6 days away. Shabbat is a very much a weekly holiday of thanksgiving. We carve out the time to push aside distractions to gather around a table to an elaborate feast with family, friends, and community in gratitude to God for everything we have in our lives.

“Although the American celebrations of Thanksgiving, Black Friday and Cyber Monday have all passed, Jews can be thankful that thanksgiving for us is never more 6 days away. Shabbat is a very much a weekly holiday of thanksgiving.“

Going back to Psalms, we find quite explicitly that the “Song of Shabbat” is the expression of gratitude itself:

Tehillim 92:1-2:

מִזְמוֹר שִׁיר לְיוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת׃ טוֹב לְהֹדוֹת לַה׳ וּלְזַמֵּר לְשִׁמְךָ עֶלְיוֹן׃

A meditative tune, a song for the Sabbath day: it is good to give thanks to Hashem, and to sing meditative praise to Your highest name.

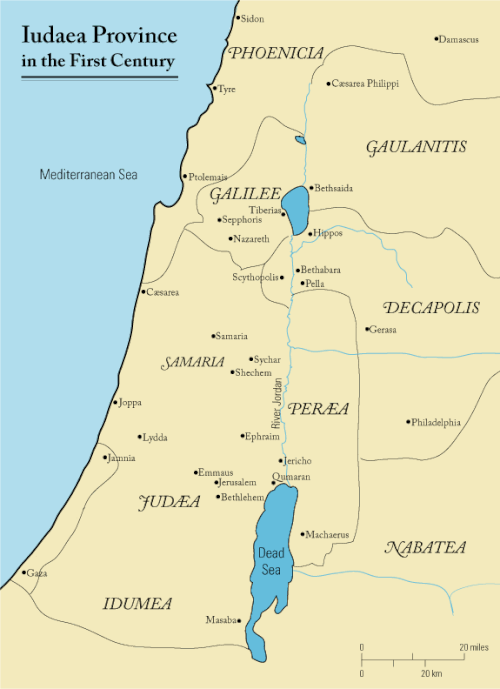

Moreover, Jews are called “Jews” (יהודים) and Judaism “Judaism” (יהדות) with this same root הוד — after the tribe of Judah (יהודה). This is because those who were left after the ransacking and exiling of Israelites by the Assyrian Empire were primarily from the tribe of Judah, living in an area that was known as Judea (יהודה) — and is still known by many today as Judea.

The original name “Judah” — Yehudah-יהודה — comes directly from the word hodaa-thanksgiving (הודאה). The reason is that his mother Leah experienced, when she had her fourth child, this moment of, “wow, this is beyond my wildest dreams.” She had thought that since there were four foremothers of the tribes of Israel, each one would merit to have three children (4 x 3 = 12), from whom would emerge three tribes. When she had her fourth, she realized that her expectations were off, nothing is really owed to her, and she felt an overwhelmed by a feeling of gratitude that inspired her son’s name.

Bereishit 30:35:

…וַתֹּאמֶר הַפַּעַם אוֹדֶה אֶת־יְ-הֹ-וָ-ה עַל־כֵּן קָרְאָה שְׁמוֹ יְהוּדָה…

…she said, Now will I thank Hashem: therefore she called his name Yehuda…

More than this: the name Yehudah (יהודה) includes God’s name (י-ה-ו-ה) — because in that thanksgiving is a recognition of God Himself.

We can ask though: why did she only feel gratitude to this extent with her fourth child? And, going back to our original question: what will it take for us get past the superficial “tysm” way of saying thank you to which we’ve become so accustomed?

In Hebrew, the full meaning of “lehodot-להודות” is more than just to “say ‘thank you’” — it is to admit and recognize the role of another. “Admission” is a word we intuitively associate with guilt — not gratitude. But think about what we’re doing when we say thank you — not in a performative, polite way, but when we really say it with our heart and soul. My sincere expression of gratitude is an admission that I couldn’t have done it without you. By recognizing what you did for me, I must recognize my own limits and vulnerability. For Leah, it was only her fourth child that broke her schema of what was “coming her way” and elicited her thanksgiving. She also modeled for her son Yehudah what it meant to verbalize her error, which he famously did many years later when he publicly accepted fault for the episode with his daughter in law Tamar.

In order to truly be grateful, I must admit that I am not an island. I’m releasing a part of my ego that would like to think I’m a self-made man, and I’m handing credit over to someone else. This is what makes true gratitude difficult even if mechanical “thank you” isn’t.

“A sincere expression of gratitude is an admission that I couldn’t have done it without you.”

Again, when we say “thanks” — or “thank you so much” to the barista at Starbucks — we may not be feeling this. But notice how much easier it is to say thank you for something small, like a cup of coffee, than it is for something massive — like thanking your parents for raising you, or your spouse for being your partner in absolutely everything. How can we do justice to what we owe them? We can’t. We wouldn’t know where to start or where to end. So we too often avoid it entirely, whereas our normal, sweet, cute, performative, check-the-box “thanks” and “thx” can continue business as usual.

This brings us to the other major meaning of the etymological root hod-הוד. It’s sometimes translated as “splendor” or “glory.” I will admit that I don’t really know what these translations are getting at other than fancy ways of saying beauty — but I can illustrate it like this:

When someone stands up to receive an Oscar or an Emmy or a Grammy, the standard, accepted thing to do is not to credit oneself, but to immediately express gratitude to all the people who helped bring him or her to that place.

But take a look at it’s opposite: imagine how ugly it would be if someone went up to receive one of those awards and gave a speech about how vindicated they feel, because they — and they alone — deserve it for all their talent and hard work.

It wouldn’t just be wrong or dishonest or unethical. It would be — on top of all those things — ugly.

If you understand this, you can appreciate how beautiful the opposite is. How beautiful it is when people express real gratitude — when they put their egos aside and recognize all those who deserve recognition, and give credit where credit is due. They become transparent prisms through which the light of the universe courses through them, and the beauty and splendor of all of reality becomes more visible.

This name was coined by Leon Jakobovits James in his 1962 PhD dissertation at McGill University. The neuro-cognitive phenomenon is still being studied.