Abraham

and his ongoing revolution

The greatest revolutions of history have changed us so dramatically that it’s nearly impossible to appreciate them in hindsight.

This is not because what they achieved was so subtle, but rather because the changes they brought to human consciousness were so profound that we now see them as obvious.

Take, for example, the scientific revolution of Galileo, Bacon and Newton. Although it’s obvious to any educated person in the 21st century that running controlled, repeatable experiments and making careful observations is the only way to verify objective truths about the physical world, this was not at all obvious to ancient people. As late as the 17th century, Galileo was persecuted and sentenced to permanent house arrest by the Church for his assertions that the data he had collected had corroborated that the earth orbits the sun — not vice versa.

I would argue that there has been no revolution more important to human history than the revolution of a Hebrew man born in Mesopotamia in the year 1812 BCE,

known to English speakers as Abraham,

to Hebrew speakers as Avraham (אברהם),

to students of the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Torah, known by Christians as the “Old Testament”) as Abraám (Ἀβραάμ),

and to approximately 2 billion Muslims as Ibrahim (إبراهيم).

Nearly two thirds of the world identifies as Christian or Muslim and traces their thinking about life’s most important questions to Abraham. Additionally, according to the mystical tradition of the Zohar, meditative mindsets and techniques central to Hinduism and Buddhism may find their source in Abraham’s teachings as well.1 Nearly four thousand years after his death, we can appreciate the prescience of his name meaning “Av Hamon Goyim — father of many nations.”

We may, however, struggle to pin down exactly what was so radical about his revolution.

One could argue that the scientific and technological revolutions that transformed agriculture, warfare, industry and medicine were more consequential than that of Abraham. Our modern lives are no doubt saturated with science and technology. But I would argue back that ultimately these areas of life are technical compared to the essential shift in human thinking brought about by Abraham.

His teachings utterly altered our sense of ourselves and others as made in the image of God — no less than we.

The beliefs he instilled in all those whose lives he touched eventually came to form the cornerstone of the greatest democracy on the planet, and are introduced in our Declaration of Independence as “self-evident”:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

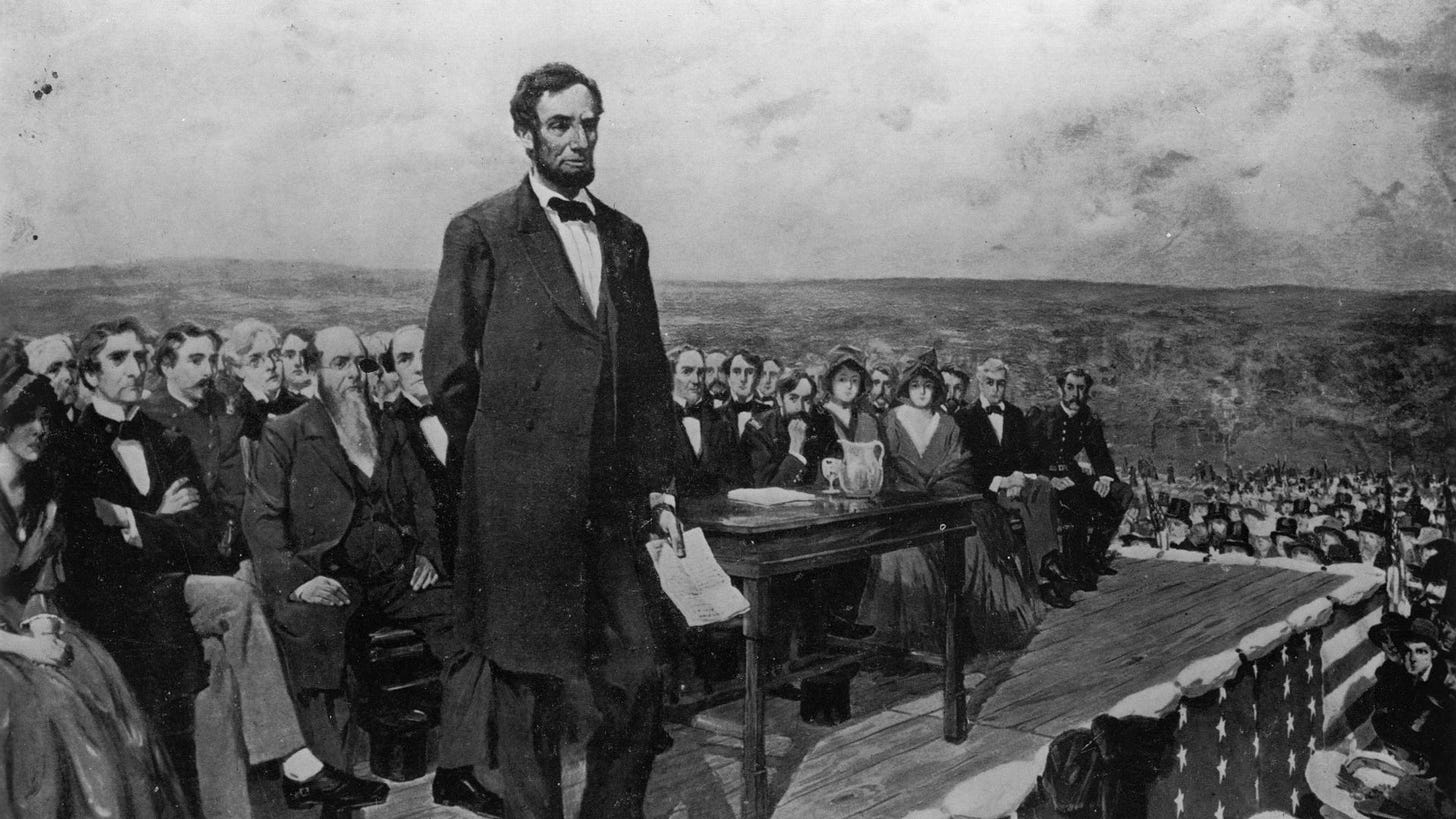

Of course, these truths were not as self-evident to everyone as the founding fathers had assumed. Nearly a century later, on January 1, 1863, a different Abraham used his executive order as president to emancipate three and a half million enslaved Americans, echoing this founding doctrine at the site of the Battle of Gettysburg:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

In the terribly tribal world that the original Abraham was born into, there was no sense of universal equality or human dignity. There was similarly no sense of objective right and wrong. In a polytheistic world governed by a pantheon of gods that didn’t get along among themselves, “right” and “wrong” were entirely subjective, depending only on which god any given person chose to subscribe to. And one could theoretically switch teams any day. There were, by no means, “inalienable rights” that anyone else was obligated by an overarching, universal authority. Why would there be?

Although idolatry may seem like ancient history to us, a tribal, chaotic world in which everyone chooses what morality means to them surely can’t be too hard to imagine.

These so-called “self-evident” truths are still in need of reinforcement.

On the one hand, Abraham’s impact is undeniable, but on the other hand, there’s still a way for us to go. In order to continue his legacy, we should consider:

How did Abraham go about leaving such a lasting impact in such a world?

In what may come to be known as the “Age of Influencers,” when memes are produced and forgotten at thumb-blistering speeds, we should ask ourselves: how can we change the way people think for the better in a way that sticks three millennia later?

I want to answer this question by raising one more:

Abraham became known for two things:

Guiding others to believe and know that there is only One God, and

doing kindness for others on a scale and in a way that had never been seen before.

Is there a connection between these two aspects of his personality and legacy?

Yes. A deep one.

Maimonides describes Abraham’s way of teaching as the opposite of indoctrinating.

Indoctrinating means to drive a belief, or “doctrine,” “in”-to someone’s head. In contrast, “education” comes from the Latin educere, which means to “lead one out” from a closed mind to a broader way of thinking:

[Abraham] would go out and call to the people, gathering them in city after city and country after country, until he came to the land of Canaan — proclaiming [God's existence the entire time]…

When the people would gather around him and ask him about his statements, he would help each one of them come to know [God] according to his unique understanding, until they turned to the path of truth.

Abraham wouldn’t impose his notion of truth onto others. Instead, he would walk by their sides along the windy alleyways of their minds until they arrived at the unavoidable conclusion to which all roads lead: everything and everyone comes from the One True Source of All.

In perhaps the most well-known piece Midrashic literature, young Abraham is featured engaging with people, whether in his father’s storefront, or in the king’s palace, through Socratic questioning:

A woman would enter his father’s store to purchase an idol, Abraham would casually ask her for her age, and she would answer. Abraham would then ask her how she justified worshipping a deity that was decades younger than she. Embarrassed, she would leave the store without the idol she came to buy.

After famously breaking all-but-one of his father’s idol inventory in an effort to elicit a response, Abraham responded to his father’s rage by blaming the one remaining idol in the back of the store. His father in turn responded with cynical disbelief that a lifeless sculpture could have done the damage. To this, Abraham asked his father, “Father, do your ears hear what your mouth is saying??”

Concerned and at a loss, his father took his son to King Nimrod who directed Abraham to worship fire or be fed to it. Abraham responded with a question: “Why fire and not water? Doesn’t water put out fire?” Nimrod conceded that water would do just fine. To this, Abraham followed up by asking, “Why not clouds? Clouds carry water, don’t they?” This back-and-forth continued until Nimrod lost his patience and ordered Abraham to be executed, which he miraculously managed to evade.

Although Abraham’s approach would initially get him into trouble, it was through this way with people that “ultimately, thousands, and later tens of thousands gathered around him,” in whose hearts “he planted this great fundamental principle [of the unity of God].”

Abraham’s revolution was not introducing a new idea that was foreign to people. His revolution was helping all individuals arrive at this “fundamental principle” of the unity of all things themselves — realizing it was there all along.

Contemplate this and you will understand why Abraham is the paradigm of love and kindness so many years later. Abraham despised idolatrous cults that brainwashed people to believe and comply, only to treat them as disposable followers.

Abraham’s movement gave people space and tools to think for themselves because he fundamentally believed not just in God — but in people as well.

His belief in the unity of God further necessitated that every person could come to the conclusion through his or her own path. True unity has room for plurality.

And finally, upon arriving at the conclusion that everything and everyone was brought into being by the same Ineffable Oneness, it would dawn on people why Abraham dedicated his life to love and care for others. The universe is not a cacophony of warring forces as it sometimes seems. The universe was created by Hashem Alone. He chose to bring it into existence — not for His benefit for what benefit could the Infinite receive from it? Rather, the universe is a gift. Abraham understood the depth of this. He understood that the gift of life is to give the gift of this appreciation of life as a gift to others in the way each of them could receive.

Abraham’s revolution continues until today because he didn’t invent something new and impose it on people.

What he did was he helped people find themselves within a world in which they had been lost.

His ideas have “stuck” for so long because they were there all along.

This notion was developed by Rabbi Moshe Shapira zt”l, and popularized by his students. The Zohar I:99b is one such classic source for tracing Eastern spiritual wisdom to Abrahan:

“Rabbi Abba said, ‘One day I happened upon a certain town formerly inhabited by children of the East, and they told me some of the wisdom they knew from ancient days. They had found their books of wisdom, and they brought me one… I found in it all the ritual of star-worship, requisites, and how to focus the will upon them, drawing them down… I said to them, ‘My children, this is close to words of Torah, but you should shun these books, so that your hearts will not stray after these rites, toward all those sides mentioned here; lest – Heaven forbid – you stray from the rite of the blessed Holy One! For all these books deceive human beings, since the children of the East were wise – having inherited a legacy of wisdom from Abraham, who bestowed it upon the sons of the concubines, as is written: ‘To the sons of his concubines Abraham gave gifts, while he was still alive, and he sent them away from his son Isaac eastward, to the land of the East.’ Afterward they were drawn by that wisdom in various directions.”