12 Flavors of Happiness: Part 3

Ahava, Achva, Shalom and Re’ut

Even though Purim has passed, we’re going to unabashedly complete our Simcha-שמחה mini-series on the 12 Flavors of Happiness this week, before returning to our broader Language of Life series studying the Hebrew language. During the month of Adar, we’re supposed to actively “increase our happiness,” and the holiday of Purim, not even halfway through the month, was certainly never intended to be a hard stop to that upwards trend.

Let’s keep the Simcha going.

(If you’re wondering why I couldn’t get “Part 3” out on Purim day, here is a window into what I was doing this past Friday👇)

Today, we’ll take a look at the final four flavors of happiness, which conclude the full spectrum of joy created by God for us to experience. When we’re not feeling particularly happy, we might even forget that they’re possible to be experienced. This is why they’re described in the final blessing under the chuppah as “creations” of God. We can conceptualize them as Divine gifts that exist — whether we’re tapping into them at a given moment or not. Knowing that they’re there, waiting for us, helps us hold out for them through hard times during which they might fade from our view.

Here are the 12:

Ahava - אהבה

Achva - אחוה

Shalom - שלום

Re’ut - רעות

The last four words for happiness introduce concepts that we normally think about as relational — love, brotherhood, peace and friendship — as experiences of happiness, which they undoubtedly are. Thinking about them in this way can help us open our hearts and minds to experience them in their authentic forms.

9. Ahava-אהבה - the joy of unity

All forms of joy are ultimately about wholeness — being or becoming whole.1

Ahava-אהבה is the experience of being one with another.

In true love, one perceives oneself — and the other — as one self.

Love is not about “I scratch your back and you scratch mine.”

It’s: “I scratch your back because I can’t stand that you have an itch.”

Famously, Rabbi Aryeh Levin (1885-1969), fondly remembered as “the Tzaddik of Jerusalem,” took his wife to the doctor for her leg pain, and opened the conversation by telling the doctor, “our leg hurts.”2

This is the secret behind the mitzvah of “Love your fellow as you love yourself — ואהבת לרעך כמוך.” The way to strive towards this ideal is to work on seeing the people around you as part of the same Self. Different souls growing on the same tree.

A big insight here is that love is not just the desire to be close to another person, but stems from a broader sense of oneness.

Love is a kind of happiness. It’s the perception and feeling of being a part of a larger whole. This is the meaning of the well-known Gematria (numerical equivalence3) that equates Ahava-אהבה (love) with Echad-אחד (one):4

“Love is a kind of happiness. It’s the perception and feeling of being a part of a larger whole.”

10. Achva-אחוה - the happiness of sharing a common source

Those who grew up in a closely bonded family rarely appreciate the magnitude of what they possess, while those who did not cannot know what they’re missing until they build a close family of their own.

Achva-אחוה literally translates to “sibling-hood” (“Ach-אח” is brother, and “Achot-אחות” is sister5), or “kinship.” Whereas Ahava-אהבה is about being one unit, Achva-אחוה is about coming from one source. Being genetically brothers and sisters is about sharing a mother and/or a father, but the experience can come from discovering a shared source spiritually.

A couple who knows only romantic love is lacking this additional track of kinship love called Achva-אחוה. The spiritual notion of soulmates is precisely this concept of stemming from the same source, like two “peas in a pod,” who understand one another without having to spell everything out, like a brother and sister who grew up together.6

11. Shalom-שלום - the contentment of complementary collaboration

The Talmud teaches that vividly seeing any of these three images in a dream indicates that Shalom-שלום (peace) is on the way: a river, a kettle or a bird.

What do these three very different images have to do with peace?

In 1987, Rabbi Aaron Feldman popularized this cryptic statement of the Talmud with his book titled The River, the Kettle and the Bird, based on the Vilna Gaon’s 18th century exposition of it.

Here’s my summary:

“Shalom-שלום” is probably the best-known word in the Hebrew language. It’s also one of the most poorly understood. When third parties demand “peace in the Middle East,” they basically just want everyone over there to stop shooting each other and stop dominating the news so they can live in peace (and quiet). In this common conception, “peace” simply means “cessation of violence.”

“‘Shalom-שלום’ is probably the best-known word in the Hebrew language. It’s also one of the most poorly understood.”

But is this all that what we aspire to?

When we greet someone with “Shalom,” are we merely telling them that we have no intent to harm them?7 When we speak of “Shalom Bayit,” marital harmony, are we simply saying that husband and wife, at the moment, have paused their attempts to kill one another?

Rather, true peace is not just a lack of aggression, but rather the positive presence increasing levels of collaboration.8 The word Shalom-שלום comes from the word Shalem–שלם, which means “whole.” The 3 images are increasing relationships of wholeness between two disparate entities:

River - Imagine two villages on a river. One produces lumber. The other wheat. They use the river to trade with each other, and both benefit. This is level 1 of Shalom.

Kettle - Fire and water are natural enemies. The very simple invention of a kettle allows them not only to coexist, but produce something that neither could do on their own. This is level 2.

Bird - The left and right wings of a bird flap in opposite directions. As the bird learns to flap them in concert, they form an integrated organism that flies, transcending itself. This is level 3.

Shalom-שלום is the joy of seeing how differences complement each other. Complementarity leads to collaboration, which leads to mutual thriving, and ultimately complete organic integration and transcendance.

12. Re’ut-רעות - the profound sense of caring for and being cared for — despite your differences

The ancient authors of the blessing on which we based this mini-series put together these 12 flavors as a full spectrum joy that newlyweds should be blessed with. In their minds, what is the final and ultimate expression of joy to be experienced?

Somewhat surprisingly, they chose Re’ut-רעות, “friendship.” We normally think about love (Ahava) as a more advanced stage than friendship, but this inverts it, putting friendship as the crown of joy. Why?

One more question before we answer:

If the Language of Life series is starting to train your eye for Hebrew, you may be puzzled to the disconcerting presence of another Hebrew word within the word for “friendship,” רע (Ra), meaning “bad.” What is “Ra-רע” doing in the word “Re’ut-רעות” of all places?!

The answer is profound and a great way to end this series, which I hope you have enjoyed, and has brought you some Simcha this Adar.

We are all pieces of an enormous puzzle. Each of us is different. Each of us is looking for our place. True friendship is not about finding someone just like us — because there is no one “just like us.” True friendship is about caring for someone and being cared for despite our differences.

The word for friend used in the Torah most famous line, “Love your fellow as you love yourself — ואהבת לרעך כמוך,” is Rei’a-רע. It shares the same consonants as Ra-רע (bad) because they both come from the word for brokenness, as in “break is with an iron pole — תרעם בשבט ברזל.” We’re all broken shards of a giant whole. What is “bad” and possibly “evil” is to perpetuate the brokenness, by living as a separate, disconnected piece of the puzzle. But the meaning of life — and the ultimate joy of life is in recognizing our brokenness and creating bonds across our differences.

“the meaning of life — and the ultimate joy of life is in recognizing our brokenness and creating bonds across our differences.”

I think about my two sets of grandparents. In both couples, the two spouses were so different from one another. One gregarious; the other more solitary. One a spender; the other a saver. I wonder how they would have fared in our modern times in which we believe that “happiness” is a synonym for “pleasure” and “comfort,” and “love” merely a more intense form of “like.” I feel blessed to have witnessed their relationships. If they could text today, I doubt they would be sending each other heart and happy face emojis all day. And yet they possessed a deep companionship, and I believe a profound happiness that we can all aspire to.

Happiness is about wholeness.

May you and your families be blessed with wholeness and all the flavors of happiness.

The works of the Maharal of Prague are replete with this principle (see, for example, Introduction to Tiferet Yisrael).

On the path to wholeness we feel Simcha.

Having achieved some aspect of wholeness we feel Sasson.

Finding our other half we feel Chattan.

Feeling the we’ve been found by the one we complete we feel Kallah.

Recognizing parts of the picture that had faded out of our awareness we feel Gila.

Overcoming challenges that stood in the way of our completion we feel Rina.

In the rush of movement towards completion we feel Ditza.

Experiencing our soul and body shift into alignment and wholeness we feel Chedva.

As recounted by the doctor during Rav Aryeh Levin’s shiva.

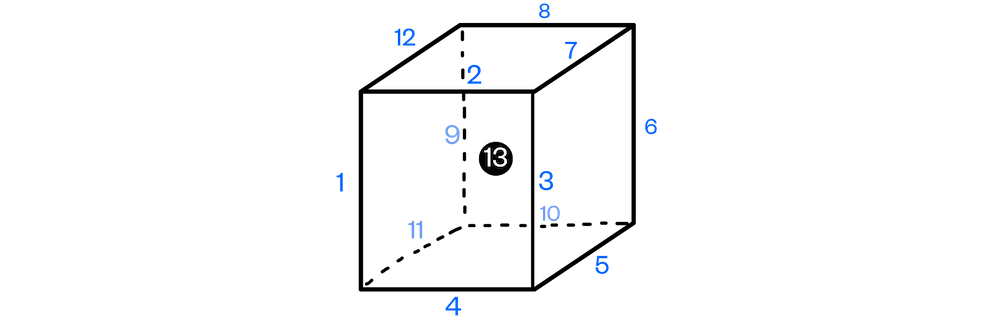

What is the connection between the number “13” and Oneness? Well, naturally there can be no word in Hebrew whose numerical equivalent is 1. The reason being that there are no one-letter words in Hebrew, and certainly there is no word “א” (the first letter of the Aleph-Bet א has the numerical equivalence of 1).

Instead, Oneness, which connotes the confluence, harmony and unity of parts is represented by the number 13. Thirteen can be visualized as the confluence of the 12 edges that make a 3-dimensional cube plus the center point that makes it real by defining its location in space and time.

The pattern appears all over the place in Torah consciousness. Perhaps most visibly in the encampment of the 12 Tribes of Israel in the desert around the Mishkan (Portable Temple), representing Jewish unity amidst diversity, which points towards Hashem as the One — “Hear, Israel, Hashem Our God is One — שמע ישראל ה׳ אלקינו ה׳ אחד.”

Note that one of the big benefits of a genderized language is the simplicity of paired words like “brother” and “sister” being, almost always, essentially the same word with modifications to connote gender (i.e. Ach & Achot). Just to give another example, “uncle” and “aunt” would be Dod-דוד and Doda-דודה, whereas “uncle” and “aunt” are completely unrelated words.

Both Avraham and Yitzchak refer to their wives as “sisters.” While ostensibly this was only to protect themselves from assault, the deeper meaning is that they perceived themselves as soulmates, two souls from the same stem on the Tree of Life.

Many believe that waving one’s hand to say “hello” originates from knights demonstrating to one another that they are not baring arms. Clinking glasses before sharing a drink similarly was to demonstrate that neither drink has been poisoned. Lovely.

“Shalom-שלום” is considered a Name of God, and should not be uttered in an unclean place like a bathroom for this reason. This also tells us that the Torah’s notion of peace is more than the anodyne notion of “peace and quiet,” but rather the positive notion of complementarity.

Thank you, beautiful. Helpful As I prepare to sing Sheva b’rachot to my eldest in May!

Excellent piece. Highly recommended to everyone, independently of the beliefs or religion. 👏👏👏👏