The Molecular Structure of Hebrew

Gender, Grammar & God

In the last post (before our 12 Flavors of Happiness mini-series), we studied the Torah’s first nod to the Hebrew language.

A lot has happened since then, so let me to jog your memory:

Hashem (God) gave the first human being (Adam) a partial lobotomy to remedy his existential loneliness. He then took the part He had removed and developed it into an entirely new creature, whom we refer to in English as “woman.” Adam coined her name in Hebrew as Isha (אשה).

Why Isha (אשה)?

It’s clear from the text that this was some sort of play on words, as Adam said, “[she] should be called Isha (אשה) because [she] was taken from Ish (איש i.e. man).”

As we saw in our last post on this topic, the fact that the Torah is able to make a play on words in Hebrew serves as evidence to two major points:

The text of the Torah must have been originally written in Hebrew, otherwise the play on words wouldn’t work.

The universe itself must have been created with the Hebrew language to explain the exquisitely precise relationship between these words.

Here’s the problem we want to address in this post:

Although it’s intuitive to anyone that words Ish and Isha are related, I would venture to guess that vast majority of native Hebrew speakers would have a hard time explaining how exactly the word Isha (אשה) conveys “having come from Ish-איש“ — with such exquisite clarity that it actually demonstrates how the Hebrew language is the very “language of life” and the “code behind the cosmos.”

We’re going to need a more granular theory of the Hebrew language — better said, a molecular theory of the Hebrew language that explains how Hebrew letters combine into words like atoms into molecules.

“We’re going to need…a molecular theory of the Hebrew language that explains how Hebrew letters combine into words like atoms into molecules.”

Join me as we continue our adventure in the Hebrew language.

Western gender roles have traditionally characterized men as dominant and insensitive, while portraying women as passive and emotional. Men who don’t fit into their box have been branded as “feminine,” “girly” or “gay,” and women who do not conform to theirs have been labeled “manly,” “unladylike,” or “butch.”

Since the 1950’s, we’ve seen notions of gender rebel violently against these rigid contours, leading to the current state of utter confusion as to what is a man and what is a woman.1 Although the MAGA right would like to blame the “Woke” left for the dissolution of gender roles entirely, the right should take responsibility for being partially wrong in how it defined “traditional” gender roles.

I believe that gender, controversial as it is, is an excellent area to study the depth and precision of the Hebrew language through the tradition that preserved it — the Jewish tradition. Hebrew is a thoroughly genderized language — every noun, verb and adjective is either masculine or feminine. At the same time, its notions of gender are far deeper and more subtle than those we’re used to, and can open our minds if we allow ourselves to.

One of the most insightful and creative teachers about the Hebrew Aleph-Bet in Jewish history was a person named Rabbi Akiva Ben Yosef (50-135 CE). It is well known that Rabbi Akiva was illiterate until the age of 40, when the woman he had fallen in love with, by the name of Rachel, saw great potential in him, but conditioned their marriage on his getting a proper Jewish education. He found his way to the greatest minds of that generation, and he himself rose to become one of them. Eventually, he raised students of his own, who became the luminaries whose opinions formed the basis of the Talmud that endures to this day.

Rabbi Akiva’s key to wisdom was: take nothing for granted. He approached the Torah with the intelligence and maturity of a middle-aged man combined with the curiosity and diligence of a child. He asked questions that most people never thought to ask, and in so doing revealed a depth and precision that was previously hidden.2

“Rabbi Akiva’s key to wisdom was: take nothing for granted. He approached the Torah with the intelligence and maturity of a middle-aged man combined with the curiosity and diligence of a child.”

Rabbi Akiva composed a book, The Letters of Rabbi Akiva, which was used in Jewish public schools nearly two thousand year ago to teach kids the secrets of the Hebrew Aleph-Bet through allegories based on the shapes and names of the letters. These allegories would serve like gradual release capsules for massive ideas about life as students matured and came to understand them.

The following is one of his teachings regarding the words Ish (איש) & Isha (אשה):

Sotah 17a:

“If a man (Ish) and woman (Isha) merit, the Divine Presence (Shekhina) dwells with them, but if they don’t merit, fire (Esh) consumes them.”

Let’s first look at this from 30,000 feet, and then we can zoom in letter-by-letter:

People are like fire. We have needs and desires and would burn everything in our way to satisfy our cravings. This is why the word for man Ish (איש) and the word for woman Isha (אשה) share the letters of the word for fire, Esh (אש). Both men and women have their fires to feed.

So what can prevent a couple from sucking all the oxygen out of their relationship in their fiery selfishness?

Only by sharing a commitment to goodness.

If husband and wife argue only for their own sides, they could burn their home down. But if a man recognizes that his perspective, although valuable, is only half of reality, and sincerely seeks to see the other half of reality from his wife’s perspective — and she, in turn, does the same — they can calm down, hear each other out, and arrive at a shared, multi-faceted truth on which their home can be built. In a home built on this sturdy foundation, God’s Presence can be palpably felt in the form of peace, care and connection.

What about in the words Ish (איש) and Isha (אשה)? Where can we see God’s Presence?

The two faces of reality are symbolized in the Hebrew Aleph-Bet with letters Yud-י and Hei-ה. The man, the Ish (איש) has the Yud-י, and the woman, the Isha (אשה) has the Hei-ה. When they come together to form a unified whole, they spell a Name of God, Yah-י-ה, which represents the sacred union of these two aspects that we will look at more closely in a moment.

Before we zoom in further, we should explain how the Hebrew Aleph-Bet works by comparing it to other written languages:

The English Alphabet is made of vowels and consonants that represent different possible sounds that they can make (phonemes), which then combine into words. This makes English phonetic.

Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphics, on the other hand, are made of individual symbols 𓀀 𓃓 𓀛 𓁀 𓂀 that represent things, figures or actions. Their letters are pictures, and are therefore considered pictographic.

The Hebrew Alpha-Bet, as understood in our tradition, is different from all other written languages. Every letter represents a deep concept that cannot be reduced into a single word precisely because these ideas are the essential elements that make up words like atoms make up molecules. It would therefore make more sense to call Hebrew ideographic rather than pictographic.

So what do the letters Yud-י and Hei-ה represent specifically?

The letter Yud-י

The letter Yud-י is the smallest letter in the Aleph-Bet, and is the only letter that floats above the line. Think of a Yud-י like a thought-balloon floating above the ground of practical reality.

It’s the 10th letter in the Aleph-Bet, representing the 10 fundamental energies of the universe (the sefirot) — but compressed into a simple dot.

The letter Yud-י is like the Big Bang before it banged — a singularity that carries in it the potential for a whole world.

Or like an idea that flashes suddenly through your mind but you don’t yet know how to implement.

Or like the potential for life zipped into the genetic codes carried by hundreds of millions of sperm, which may or may not result in a new person in the world.

If you grasp the concept behind the floating Yud-י, you will understand why in Hebrew grammar, the letter Yud-י placed before a verb turns it into future tense.

For example, Achal–אכל means “he ate,” but Yochal-יֹאכַל means “he will eat.”

The future has not yet happened. The future exists only as a floating, abstract thought in our minds, if at all.3

It’s not that the Yud-י represents these things, but rather that these things represent the idea behind the letter Yud-י. Just as Hebrew letters are the stuff of Hebrew words, the ideas they represent are the stuff of life.

“Just as Hebrew letters are the stuff of Hebrew words, the ideas they represent are the stuff of life.”

The spiritual energy behind the letter Yud-י is what makes a man an Ish (איש). Masculinity is conceptualized in Hebrew as infinite potential that is waiting to be realized.

The letter Hei-ה

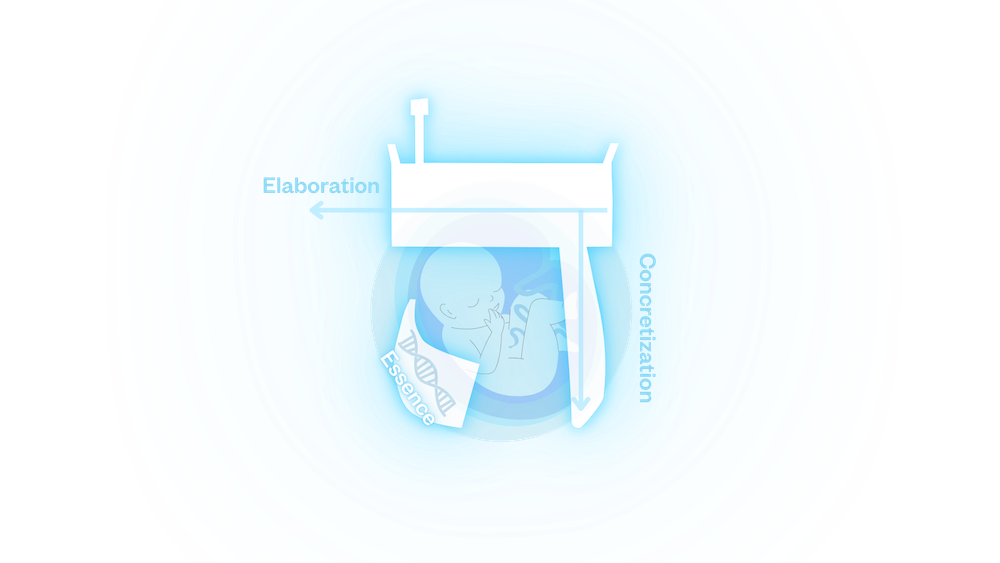

Hold this concept side-by-side with the letter Hei-ה, which is a Dalet-ד (the letter just before the Hei-ה) that is “pregnant,” so to speak, with a Yud-י.

In contrast to the abstraction of the Yud-י, Hei-ה represents concretization and specificity.

The Dalet-ד is the 4th letter in the Aleph-Bet. It represents the four directions of the physical world. The Hei-ה is the expansion of the essential kernel of potential in the Yud-י in breadth through elaboration, and depth through concretization.4

Now, think about the grammatical function of the letter Hei-ה. Putting a Hei-ה in front of a noun turns it from general and abstract to specific. While Sefer-ספר means “book,” HaSefer-הספר means “the book” — as in, the concrete, specific book being referring to.

Consider now that this is precisely the notion of femininity as defined by biology. While a man contributes abstract potential for life in the form of those hundreds of millions of potential humans (Yud-י), a woman’s egg selects a single one of those potential humans to develop into a viable embryo (Hei-ה). Then, pregnancy does the same thing. It is the process of gestation and development of the zipped-up potential in the selected DNA (Yud-י) into a full, robust organism (Hei-ה).

In the same way, while tons of people have random ideas for start-ups and inventions that pop into their heads while they’re in the shower, very few people select any one of those ideas, and put in the time, discipline and creativity energy to develop it into something real. It’s this focus and process that is at the heart of femininity in Torah consciousness.5

Femininity is conceptualized in Hebrew as the giving of substance and real expression to otherwise unrealized potential.6 It is this notion in the letter Hei-ה that makes a woman an Isha (אשה).

When these two aspects are brought together, the Divine Potential of the Yud-י with the Divine Manifestation of the Hei-ה, life is created and we can see Hashem’s Name Yah-י-ה before our eyes.

When Adam said, “[she] should be called Isha (אשה) because [she] was taken from Ish (איש),” he meant that previously, he possessed both the direct connection to pure wisdom and the capacity to manifest it in the physical world, but when he saw this new creature in all her glory, he immediately recognized and understood that Hashem, in His wisdom, decided to take the feminine part of him and make it into someone who would balance him and make him whole. This is why he called her Isha (אשה).

Once we start learning the art of curiosity from Rabbi Akiva, and begin to read Hebrew in this way, worlds open up for us.

We start asking questions:

Why does the Hei-ה has that little antenna on it, but the Yud-י doesn’t?7

Why is the word for “male” (זכר) literally mean “memory,” and the word for “female” (נקבה) means “verbal articulation”?8

Why is it that in the word איש, the Yud-י is in between the א and ש of אש, but in the word אשה, the Hei-ה appears after the word אש (fire)?9

This curiosity fuels our never-ending exploration of Hebrew, Torah and life.

Stay with us as the journey in the Language of Life continues.

I recommend you listen to Camille Paglia’s and Douglas Murray’s insightful comments about the implosion of the notions of gender as the West crossed into the post-modern age. Note that neither of these should be taken to be classical social conservatives. Paglia is an atheist, a feminist, herself a lesbian, and has identified as transgender. Douglas Murray is openly gay.

One of his prime students Rebbi Shimon bar Yochai, expanded this body of wisdom in the teachings of the Zohar, which is permeated from beginning to end with the wisdom of the Hebrew Aleph-Bet.

See Rashi on אז ישיר.

See Igeret HaTeshuva III:4 of the Baal HaTanya.

This is why it is traditional to sing “Eshet Chayil” at the Shabbat dinner table celebrating our feminine development of the potential Hashem gives us. This is also the reason why God is most often alluded to with male verbs and pronouns. Vis a vis us, He is providing potential, which we develop.

This said, when we refer to the Shechina (God’s Presence), we speak of it as feminine, as God’s Presence is manifest as a function of what we do — making us the masculine spark that is developed by Hashem, functioning as the feminine.

Men tend to be more intellectually detached from their emotions, and tend to socialize more about abstract topics like the economy, sports, ideas, world politics — things that don’t have much to do with their actual lives.

Whereas women tend to be more verbal and emotionally integrated, and tend to socialize more around events and dynamics in their actual lives than men do.

Please note that these are tendencies that can manifest in different ways with some men with more of a feminine side, and some women with a more masculine side.

If you are interested in further exploring the framework for gender in Jewish thought, I recommend Miriam Kosman’s excellent book, Circle Arrow Spiral (2014).

The “antenna” you may have noticed on the Hei-ה is called a “tag.” Some letters have three together, which look like a crown, and are aptly called “ketarim” (crowns). Here’s an article if you’re interested.

Zachar (זכר), the word for “male” means “remembers” because the idea of tapping into that floating knowledge is a form of memory. What’s manifest in the world doesn’t need to be remembered. It’s right in front of us. Instead, Nekeva (נקבה) means “articulation“ (See this passuk with Rashi’s commentary).

I have never read such a beautiful thought out post. Period. On gender and Torah? Non existent. You managed to beautifully explain the differences of gender and how they are portrayed in the Torah without any negative attitudes or assumptions about women. I am sharing this comment as a woman, who is struggling and working on reconciling narratives taught in the name of the Torah and the goodness and morality I have seen in the Torah. Your post gave me a lot of hope for continuing to try to reconcile.