Our Heart of Stone

and the Heart of Flesh Beneath It

One of my favorite verses from Tanakh is from Ezekiel’s vision of the future (i.e. our present) in which he prophesied what would happen after God would “extract [Jews] from the many cultures [of the world], and gather them in from all the lands” to bring them to their ancestral land of Israel.

Before I share with you my favorite verse, bear in mind how utterly absurd the notion of the ingathering of the Jewish exiles is.

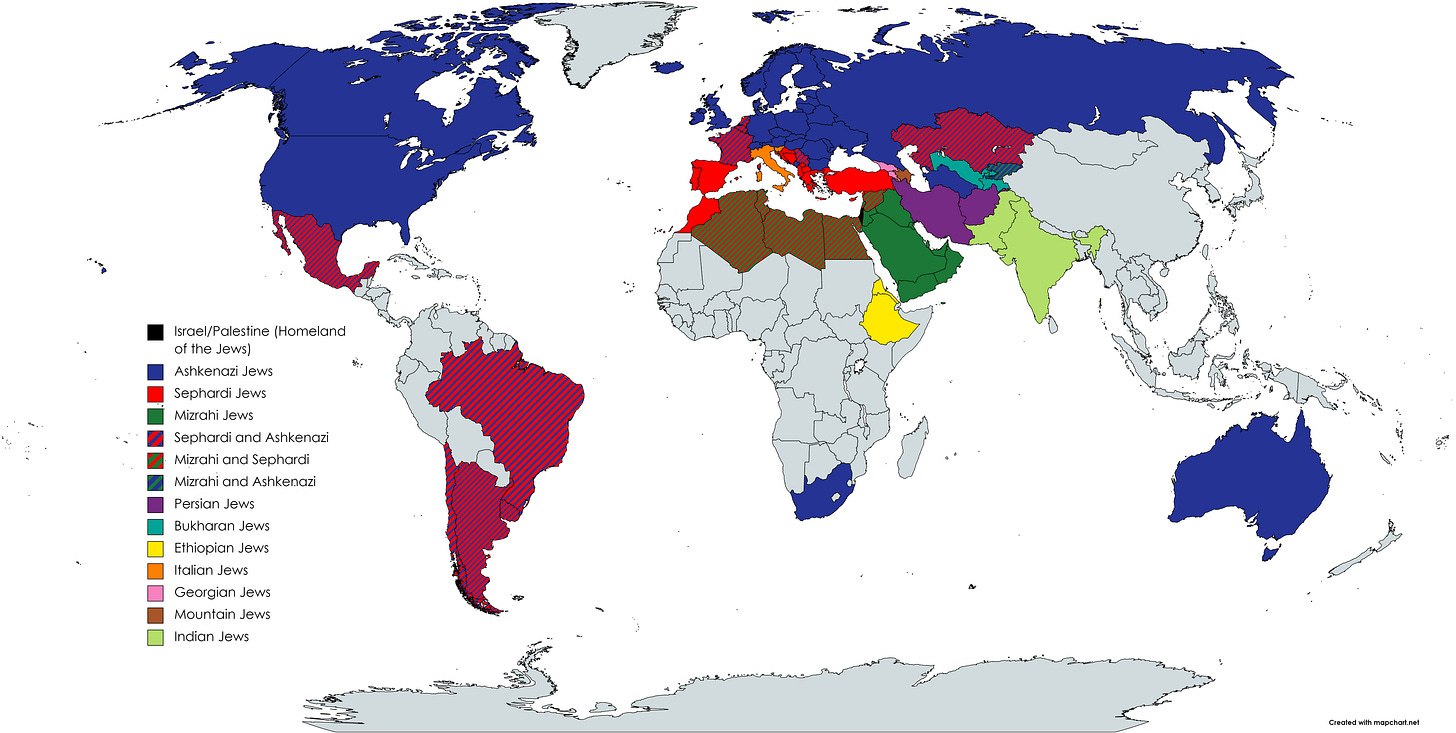

Millions of Jews were strewn across the globe from Los Angeles to Santiago to Dublin to Tangiers to Shanghai to Sydney — many of them established for centuries in their host nations — with local schools, shuls, sources of kosher food, and businesses to support their lives there. They spoke the languages of their non-Jewish neighbors, ate similar foods as them, and had similarly pigmented skin.

Why and how, after millennia of forced expulsions and migrations from one place to another, would Jews return in such massive numbers to Israel?

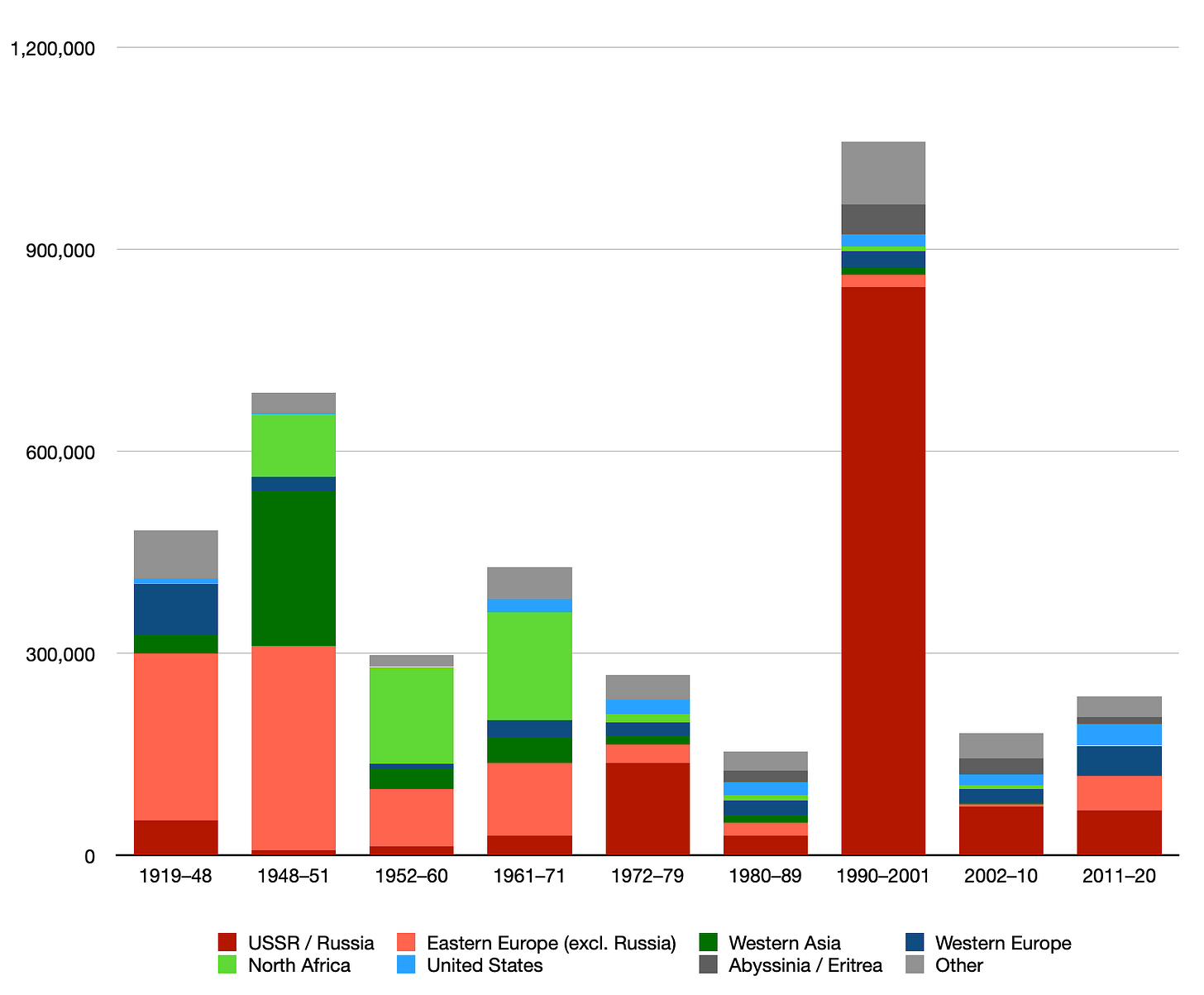

The answers to this question is overshadowed by the brute fact that Jews did return in massive numbers to Israel from the literal four corners of the world.

Our own eyes bear witness to Jews continuing to make aliya to Israel by the tens of thousands every year — a phenomenon which has no analogue in any other people in human history.

Chinese expats are not moving back to China — not after two or three generations in the Americas, and certainly not after eighty generations (the rough equivalent of two thousand years). The grandchildren of Chinese Americans are Americans in every respect, and with every generation, their connection to and likelihood of moving to the country of origin of their ancestors gets closer and closer to zero.

There is no conceivable motive or mechanism for an ethnic group to preserve its original identity and return to the country of origin of its ancestors after even a couple of generations.

If we truly allow ourselves to see it for what it is, the return of millions of English, Moroccan, Russian, Iranian, Iraqi, Argentinian, Canadian, American Jews moving back to Israel shatters the rigid conception in our imaginations of what is possible, and blows apart our hardened notions of race, culture, religion and identity.

All of this is to bring us to one of my favorite verses (I hope it doesn’t disappoint you):

וְנָתַתִּי לָכֶם לֵב חָדָשׁ וְרוּחַ חֲדָשָׁה אֶתֵּן בְּקִרְבְּכֶם וַהֲסִרֹתִי אֶת־לֵב הָאֶבֶן מִבְּשַׂרְכֶם וְנָתַתִּי לָכֶם לֵב בָּשָׂר׃

And I [God] will give you a new heart and put a new spirit into you: I will remove the heart of stone from your body and give you a heart of flesh.

A heart of…flesh.

After all that.

After all the Messianic buildup of black, white and brown Jews returning to Israel in their turbans, black hats, and knitted kippot, all we get in exchange is a plain, regular, fleshy human heart???

Yes.

At the core of our prophetic visions of utopia are not grandiose miracles, but simply an open, feeling, beating heart.

What — we may ask — is wrong with our heart now?

What’s wrong with our heart is that it’s not really a heart at all.

It’s a heart of stone.

When we’re with other people, we are too often conversing — not with them — but with our stale image of them. We don’t see them as who they are, but who we imagine them to be. Even if they were to say something unexpected, it wouldn’t register in our minds — precisely because we didn’t expect them to say it. Our hearts are not doing their jobs of truly experiencing the reality in front of us. Our hearts are hearts of stone.

The human imagination is described in the Torah as a “heart of stone” because our minds have frozen reality into a collection of static images of what we imagine it to be, preventing us from seeing it as it really is. It is this dynamic of superficial perception that powers the racism, sexism, bigotry and xenophobia that many see as the scourges of the modern world, but it goes far deeper than these problems, which we’ve fixated on as “the issues.”

There is an issue behind these issues.

Our hardened sense of the things limits the way we see our spouses, our children, our coworkers, and ourselves. It limits our ability to see something new in an old Torah, and to learn from the sources we’ve long ago written off as patently false.

We don’t live in the world. We live in our imaginations.

Is there anything we can do about this?

Yes!

The very fact that the world is changing at the pace that it is should wake us up to reality being so much more than what we ever imagined. The existence of Israel should shatter our very-limited expectations for what is possible. Whatever we have imagined God to be since we were children should be replaced by reality as it unfolds before us as hopefully humbled adults.

Humility is a great thing. As we grow up, life teaches us that the fact that a picture is vivid in our minds doesn’t make it true. Our judgements about other people and ideas are often proven wrong, and our minds tend to open in the process.

Rebbe Nachman of Breslov (1772-1810) took this one step further:

At every stage of perception, what we are seeing in our mind’s eye is a shell and shadow of what we will come to know it to be at the next, more evolved stage of perception.

For this process of continual learning to work, we have to realize two things:

how small we are in the big scheme of things, and

how awesomely and inconceivably great Reality (i.e. Hashem) is.

Reminding ourselves of our limited perspective, and preserving our sense of the infinite depth of the universe, keeps us looking and learning. If we do this, we can continually shed prior superficial understandings of people, situations, ideas, and ourselves, and keep searching for deeper and truer understandings.

Rebbe Nachman uses vivid imagery to give us this self-awareness of our own imagination.

The Talmud speaks of a worm called “the Shamir” that was used in the construction of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem (the Beit Hamikdash). This creature was employed by King Solomon since metal instruments were not allowed given that metal tools remind one of weapons of war, and the Beit Hamikdash was meant to be a place of peace. The Shamir is said to have moved along a straight line on the surface of the stone, secreting some kind of chemical that would soften the stone along that line, allowing for a clean break without resorting to steel instruments.

In addition to this worm, the Sages speak of “Nofet Tzufim,” an exceptionally sweet kind of honey that existed during the First Temple period.

Lastly, the Shamir and the Nofet Tzufim are associated in the Mishna with “Anshei Amana” — people of true faith, who lived in that time period.

Rebbe Nachman explains: these three seemingly disconnected elements describe the cognitive process of learning that can transcends the mental superficiality that stops us from living in God’s magnificent world.

The Shamir represents the perspective of humility. In an important sense, we are just caterpillars inching along our corners of the world. We can barely see what’s right in front of us — let alone everything around us.

Knowing how much we don’t know ironically helps know so much more.

Humility cracks open the hubris of our hearts of stone created by our imaginations.

But it’s not enough.

We also have to train our minds to think deeply.

Whether we are learning Torah, or we are getting to know another person, we have to be humble enough to realize we almost for sure are wrong in our snap judgements, and certainly don’t see the full picture. But we also need to go beyond this to ask questions to discover what is right.

What IS the Torah trying to meaningfully communicate to us here? Who IS this person in front of me? What are they trying to tell me?

There is nothing sweeter than discovering the Divine wisdom in the Torah, or the depth and insight of another person made in the Image of God. The pleasure of understanding is represented by the exquisite Nofet Tzufim honey.

Doing this and living by this is what produces Anshei Amana, people of true faith. Emuna-Faith is maintaining the belief that the world is Divinely deep and rich. Emuna-Faith is what opens us up to keep growing and becoming more than what we were yesterday. We want to be deeper, more sensitive, more perceptive, more understanding, more sophisticated, more open-minded. Learning to enjoy real learning is the only thing that moves us in this direction.

The ingathering of the exiles is shocking even for those who believed that it would one day arrive. It was meant to be shocking. It was meant to open our minds to the world being different. Through it, we are realizing that being Jewish is more than being Ashkenazi or being Sephardi or being Chassidic. Through it the world will better grasp what it means to be human. Through it, all of us will — with Hashem’s help — shed our hearts of stone, and once and for all, have beautifully real and true hearts of flesh.

Hashem's biggest compliment of Moshe rabbainu, איש ענו הוא,.

The humblest of all men