Leadership

is about Uplifting Others

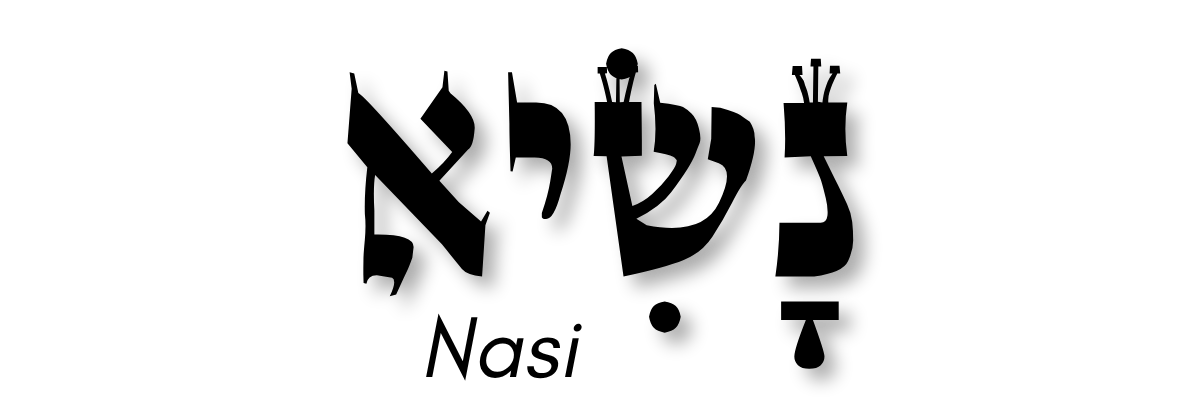

The Hebrew word for a prince or president is Nasi-נשיא. It’s first used in the Torah when the Hittites greet Abraham with the honorific title “N’see Elohim-נשיא אלקים, “prince of God.”

It’s later used to refer to the “N’siim-נשיאים,” the leaders of the twelve tribes.

The title of Nasi was later used from the 2nd century BCE to the 5th century CE for the most prominent rabbinic sage of the generation who would lead the supreme court of the land (the Sanhedrin), and would also serve as the official intermediary with Roman authorities. The most famous of these N’siim were Hillel the Elder, Rabban Gamliel I and II, and Rebbi Yehuda “HaNasi.”

The official position of Nasi was abolished in 429 CE by the Byzantine government who was concerned about Jews having too much power and autonomy.

The term has been used more informally since then for certain Jewish community leaders, and was reestablished as a formal, non-partisan position in the Modern State of Israel who presides over certain important appointments, national ceremonies and is meant to serve as a balancing, moral voice. The position is currently held by Isaac Herzog, whose father Chaim Herzog was the 6th Nasi of the Modern State of Israel, and was named after his grandfather Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog, who was the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of the State.

At first glance, the term Nasi-נשיא would come from the word Linso-לנשוא “to uplift,” ostensibly since the president is lifted above everyone else in order to lead.

The problem is that if this were the case, the grammar would be wrong. If the meaning of “Nasi” were “lifted above,” he should be called “Nisu-נְשׂוּא” in the passive voice.

Rather, “Nasi-נָשִׂיא“ more precisely means “one who uplifts others.”

Nasi-נָשִׂיא“ more precisely means “one who uplifts others.”

A leader is defined not by his position over those he leads, but by his positive impact on them.

The founding fathers of the United States were concerned when they established this great country that its government could become taken over by career politicians, who are perpetually campaigning to preserve their elevated status. They understood this dilemma of the inversion of leadership that defines itself by its position instead of its true impact. They set term limits, checks and balances, and tried to imbue the people with the values of public service to combat this tendency.

We may not be able to fight City Hall, and certainly not the White House or the Capitol. But in whatever position of leadership we find outselves in, whether as managers where we work, teachers in the classroom, or as parents at home, we should remember that our leadership is defined by our willingness, commitment and success in elevating those who look to us to be uplifted.

Interesting! I hadn't realized that what we call in English as Israel's President is actually Nasi. That makes sense - but I realized only upon reading this that I had never actually considered what the Hebrew word for President even was. I also find it fascinating in comparison to the story of why the United States picked President as a title (as opposed to King - which was considered at some point). The founders of the United States wanted to throw off any story that would tie the government to a monarchy or the old way of doing things. The modern state of Israel wanted to call back to its previous version's as a reminder that Jews had lived and governed themselves on that land before. Another reminder of how and why the words we choose tend to reflect larger stories.

So Important—-to understand meanings of words, especially Hebrew.