Dreams

Realities We Can't Conceive of While Awake

One of the great mysteries of life — biologically, psychologically, and spiritually — is the immense amount of time we spend sleeping and dreaming.

The average person, over the course of their lifetimes, will spend over two decades worth of time sleeping, and nearly 7 years dreaming.1

I invite you to ponder these staggering numbers for a moment.

Why is it necessary for us to dream at all?

Why can’t it be that while our bodies are physically recuperating at night, our minds are completely blank?

If we look at the Torah, the question gets compounded, because dreams occupy an outsized chunk of the narrative — certainly in the book of Bereishit-Genesis.

Why is so much precious ink spilled on the unreal mindscapes of the subconscious?

The cast of characters and the contexts of their dreams are also noteworthy:

Avimelech, the would-be sexual predator, king of the Philistines.

A penniless Yaakov, unexpectedly, as he sleeps on rocks while on the run from his brother Esav.

Lavan, Yaakov’s conniving father-in-law, on his way to do something terrible to his son-in-law.

Yosef, whose dreams of grandeur backfire, leading ten of his brothers to lower him into a pit with intent to forever extinguish him and his dreams.

The Head Butler and Baker of Pharaoh’s court in a royal dungeon for less than petty crimes.

And then there are the dreams of Pharaoh that shook his whole kingdom, and changed the course of world history.

What’s going on with all these dreams, and how might they help us understand our own dreams — or lack thereof?

The tool we’ve been trying to arm our readers with in the Language of Life series is:

If you have a questions in Life or in Torah, start by looking closely at the Hebrew words themselves.

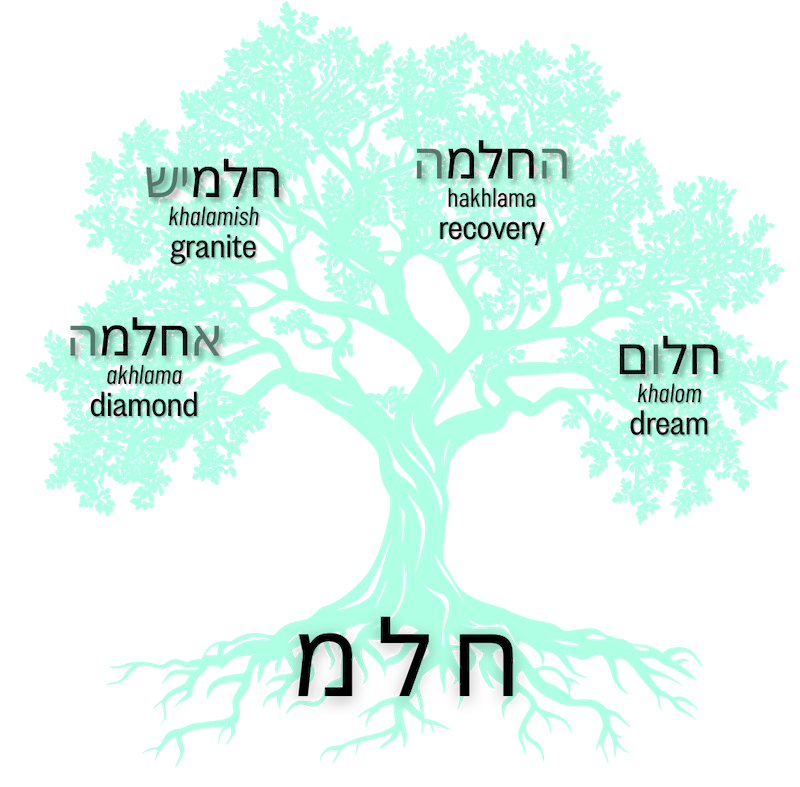

The word for “dream” in Hebrew is khalom-חַלוֹם.

How might this help us?

Let’s make some connections. Every Hebrew word has a root, a shoresh-שרש, usually made up of three letters.

The words that branch out from that root help us triangulate its meaning. As we better understand the root, our understanding of its individual branches deepen.2 In our case, these connections may initially raise more questions than answers, but ultimately, they’ll help us get closer to the deeper meaning of dreams.

The root chet-lamed-mem (ח-ל-ם) is most immediately recognized as the root of the verb lakhlom-לחלום, which means “to dream,” but is also connected to the word lehakhlim-להחלים, which means “to recover medically,” which naturally begs the question:

What’s the connection between dreams and recuperation?

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch explains, in his richly linguistic commentary on the Torah, the root ח-ל-ם to mean the reconnection of estranged parts.3

When someone is recovering, their body is reintegrating itself. If a person suffers an injury that isn’t treated, and the limb doesn’t receive enough blood or drain out toxins, he or she could end up requiring amputation, the ultimate disconnection. If the injury is treated on time, however, the body can begin to reconnect the limb into its holistic system. The same is true if a person gets sick. The body first wages war against the disease, and then begins to restore and reintegrate itself. Hakhlama-החלמה, healing, is the reintegration of all of ones parts into the whole, which is the hallmark of health.

Dreaming, then, can be thought of as a sort of spiritual recovery that our psyches must undergo regularly, just as our bodies must every night. Over the course of any given day, and certainly over the course of our lives, all of us become somewhat estranged from our hopes, dreams and aspirations. When we allow ourselves to dream, we are able to reconnect with those aspects of ourselves before they float away from us completely.

This helps us understand a startling statement in the Talmud:

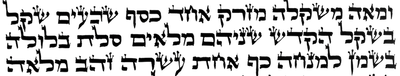

Talmud Berakhot 14a:

…וְאָמַר רַבִּי יוֹנָה אָמַר רַבִּי זֵירָא: כָּל הַלָּן שִׁבְעַת יָמִים בְּלֹא חֲלוֹם נִקְרָא ״רַע״

Rabbi Yonah said in the name of Rabbi Zeira: “Anyone who sleeps soundly for seven days without a dream is called “evil” (רע).

Why would this be? Wouldn’t bad dreams specifically be a problem? What’s wrong with not dreaming at all?

If you meditate on what evil is in its essence, you will eventually arrive at some notion of disassociation and estrangement — the alienation and cruelty from which all bad things stem.4 It’s for this reason that the only day in the 7 Days of Creation that is not called “tov-טוב (good)” is Day 2 — the day of division, when the waters were separated, and nothing new was created. It was Day 2 that introduced the notion of opposites, which never the twain shall meet.

By looking for other words that share the etymology of ra, we find another illustration of evil as disconnection:

The teruah sound of the shofar is meant to conjure for us the staccato, shattered sound of a person uncontrollably sobbing. The word "Teruah-תרועה” comes from the same root as “ra-רע (evil).”5 We cry in a shattered way when our lives feel like broken, disconnected pieces with no hope of ever coming back together.

Now, we can understand why someone who stops dreaming is called “ra.” He’s become so estranged from his higher consciousness that even when his judgmental lower consciousness is unconscious (i.e. he’s sleeping) he still cannot hear his soul’s intuitions.

When people stop dreaming, they’ve closed out all possibilities about who they can become or what the world could be. The lack of dreams is a symptom of a spiritual disconnection that must be healed. As people begin to heal and reintegrate their practical, rational selves with their intuitive, expansive, open selves, they can begin to dream again.

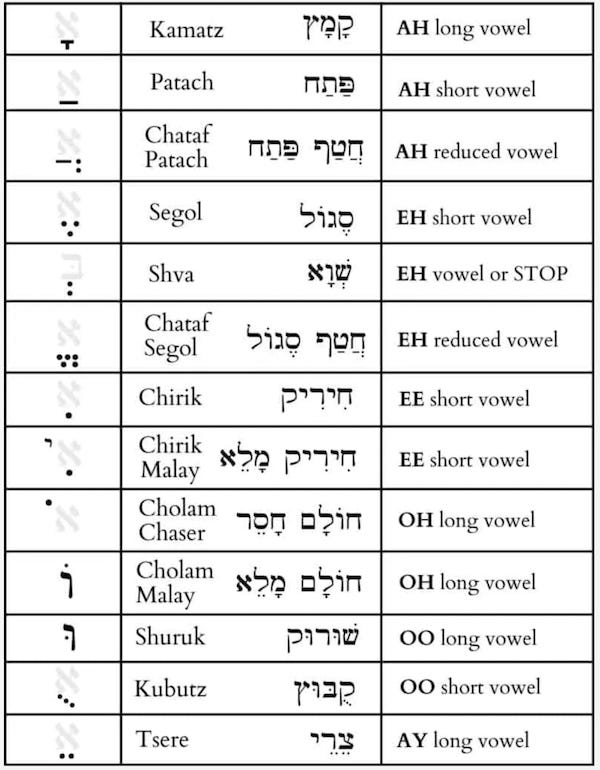

You probably know that Hebrew is built out of consonants. There are 22 consonants that get strung together in the Torah without explicit vowels to indicate how to pronounce them.

The implied vowels have names and symbolic forms called “nekudot-נקודות,” literally, “dots.”

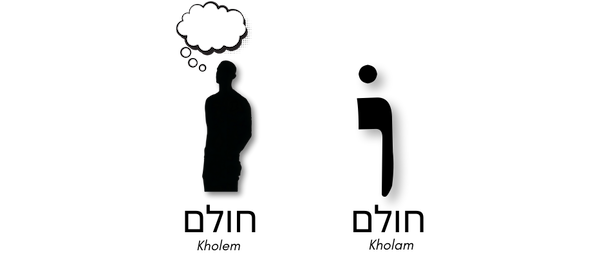

There is a vowel whose name is essentially the same as the word for dream: “kholam-חולם.” It looks just like the letter vav, the sixth letter in the aleph-bet, with a dot hovering above it.

In his Kabbalistic work Sefer Hanikud, Rabbi Yosef Gikatilla (1248-1305) opens his exploration of the meaning of the Hebrew vowels by discussing the kholam, which he describes as the highest and most spiritual of all the vowels — the one that represents the connection to the infinite and impossible-to-capture. The dot on top represents that which is so close but so far, and the vav visually represents the integration down to the ground. The letter vav grammatically means connection by functioning as the conjunction “and,” and the word “vav” actually means a “hook” or “connector.” So, the kholam symbolizes connecting with that which is otherwise disconnected from a person a.k.a dreaming.

Dreams introduce us to ideas, visions, desires, possibilities that we can’t fully understand or visualize in practical terms. Not only would we not be able to comprehend them if we were awake and conscious — we would outright reject them as absurd. This is precisely why we must dream. If we have any hope of the status quo changing, we must allow ourselves to dream of that which we would otherwise see as impossible.

When we sleep, we are more loosely tethered to the world around us. This looseness allows us to consider possibilities that don’t yet make sense — and to be okay with them. This thin connection to those possibilities allows us to begin building bridges to a future that is incomprehensibly far from us now.

The Book of Bereishit is full of dreams is because in that lawless, Godless, ancient world, there was no rational reason why things shouldn’t have just descended deeper and deeper into violent, pagan tribalism. No intelligent person would have accepted the future, which we now know as reality, and certainly no one could have imagined the utopian future that yet awaits us.

The king of the Philistines, the king of Egypt, Jacob’s father-in-law were all men who were closed to the status quo changing precisely because of the power they wielded. God had to circumvent their egos by coming to them in dreams.

So too, Yaakov running into the unknown away from his brother — only a dream could have shown him that everything would be okay.

Yosef’s dreams reflected his desire to lead, but he could never have understood how they would play out. In the short term, they backfired. He shared his dreams with his brothers and they hated him even more. Instead of bowing their heads before him, they threw him into a pit. But decades later, in the unlikely setting of an Egyptian royal palace, those dreams came to be.

The whole saga of Yosef itself was like a dream. His leadership, though brief, introduced an idea into the Jewish psyche: that leadership is possible — that unity is possible. That idea was the seed that would eventually grow into the concept of Jewish kingship.

Devarim 33:5:

וַיְהִי בִישֻׁרוּן מֶלֶךְ בְּהִתְאַסֵּף רָאשֵׁי עָם יַחַד שִׁבְטֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל׃

He was king in Yeshurun, when the leaders of the people and the tribes of Yisra᾽el were gathered as one.

Israel’s current national anthem centers around hope — ha’tikvah-התקווה, literally “the hope.” Hope is a vague sort of optimism. Some have critiqued the anthem for representing too low of a bar for the future we as Jews should aspire towards. We should want more for the ourselves and the world than “to be a free nation in our land — להיות עם חפשי בארצינו.”

It’s interesting to note that one of the other candidates for Israel’s national anthem was a line from Tehillim-Psalms — attributed to King David — recited by many before Birkat Hamazon (Grace After Meals) on Shabbat and holidays:

Tehillim (Psalms) 126:

שִׁיר הַמַּעֲלוֹת בְּשׁוּב ה׳ אֶת־שִׁיבַת צִיּוֹן הָיִינוּ כְּחֹלְמִים׃

A Song of Ascents:

When Hashem restores the captivity of Zion, we will have been like dreamers.

As the Jews return to Israel, we will see ourselves as dreamers. On one level, we’ll realize we were asleep in our exile. But on another level, we’ll realize that our subconscious — or better, our superconscious — kept us connected. Not just to a glimmer of hope. But to a vision. To a dream.

Our dreams are always partially-self-fulfilling prophecies.

Sleeping: 7 hours per night x 365 nights x 80 years = 204,400 hours = 8,516 days = ~23 years of sleep

Dreaming: 2 hours per night x 365 nights x 80 years = 58,400 hours = nearly 7 years of dream time.

If you’re interested in exploring how these roots work, check out this etymological dictionary of Hebrew, based on the writings of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch.

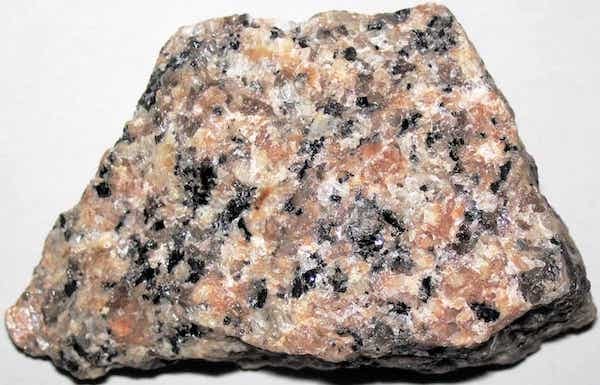

Perhaps going out on a limb, he proceeds to claim that the root .ח.ל.מ is also related to the word khalamish-חלמיש, which he understands to be what we call “granite,” and the precious stone achlama-אחלמה.

It turns out that that’s what granite is: minerals pressed together under immense pressure.

Apply even more pressure, and you get diamond, yahalom-יהלום, which would also be connected to our linguistic tree above using the concept of interchangeable letters (אותיות מתחלפות), which posits that letters from the same source location can be interchanged while preserving semantic connection.

Hebrew letters are organized according two the five locations from which their sounds emerge in the body of the speaker:

Lips – בומ”ף

Teeth – זסשר”ץ

Pallate – גיכ”ק

Tongue – דטלנ”ת

Throat – אחה”ע

The word for cruel is akhzar-אכזר, which can be broken down into two words ach-אך zar-זר, meaning “only strange.” A cruel person has become completely estranged without empathy for others.

As in the verse in Psalms:

Tehillim 2:9:

תְּרֹעֵם בְּשֵׁבֶט בַּרְזֶל כִּכְלִי יוֹצֵר תְּנַפְּצֵם׃

Break them with a rod of iron; shatter them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.

Excelente Jack”i” ! Thank you for such inspiring essay. Wonderful