Cut Through the Noise

The Art of Not Getting Sucked into Intelligent Stupidity

Question:

Help! I’m suffering from information overload. Just thinking about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict makes my head feel like it’s going to explode.

There are so many facts to juggle — so many perspectives to balance. Both sides have their legitimate narratives. People are suffering, and both sides are mourning terrible tragedies…

It’s just so complicated. I don’t know what to think anymore…

Advice from the Sages:

I completely relate to your sentiment. I definitely have my own moments when my head feels like it’s going to explode.

The universe is vast and complex, human beings are complicated creatures, and life is unendingly nuanced and full of contradictions.

Nevertheless, there are simple truths, which our lives depend on, that get obscured through over-complication.

Especially in our post-post-modern reality, in which everyone has his or her own “truth,” and we are barraged incessantly with soundbites, opinions, testimonials, and evocative images and videos — our core beliefs must remain crisp and clear for us to be able to make meaningful decisions we can feel confident about. Without this clarity, we are lost.

Put differently:

Our ability to successfully navigate our world’s complexity depends on our clarity regarding the simplest ideas.

What hope is there for having an intelligent conversation about the war in Gaza if we cannot establish whether or not there is a difference between targeting civilians or targeting those who target civilians?

The answer to this question happens to also be simple:

None.

My point here is not to reduce our discourse to Trumpist slogans or pithy Wokisms. I am trying to convey the need for thinking about complexity at its root.

Let me illustrate with a common example. People often engage in debates about push-button issues, like abortion, and proceed to talk past one another until they are blue in the face, at which point they may agree to disagree, and promise themselves to never revisit the issue again in conversation. No one walks away from these pointless conversations smarter, better informed, or with sharper arguments — just worn out and disillusioned with the notion of speaking to those who think differently from them.

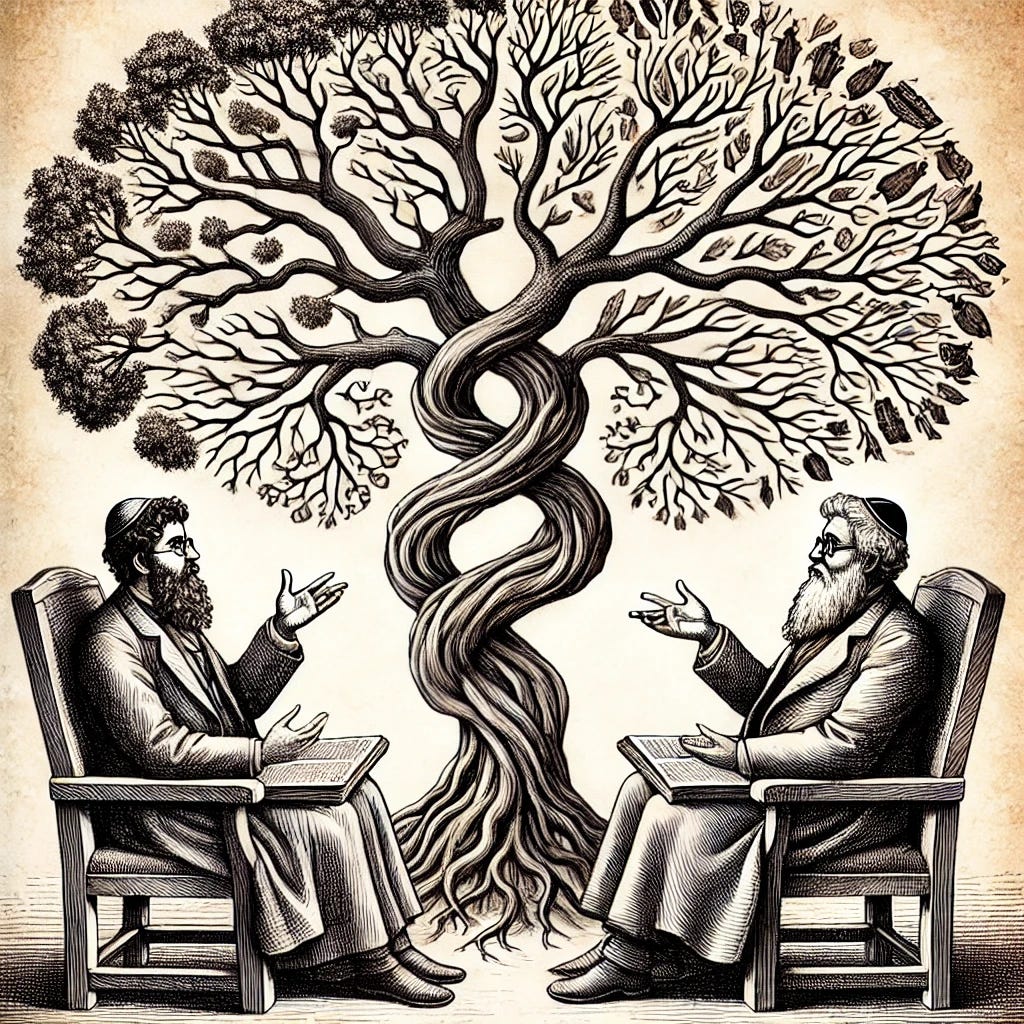

Those who have studied Talmud in depth no doubt have encountered the notion of revealing the “point of dispute — nekudat hamachloket” in any given debate. It is axiomatic that any argument between Rava and Abaye or Rashi and Tosofot or any other two or more parties must emerge from the juncture at which the perspectives diverge. This means that they agree up to that point, and because of that particular difference in perspective they disagree after that point. This is one way to think about why the Torah is called a “Tree of Life.”

I cannot emphasize enough how important this way of seeing is.

While it is tempting to believe that someone who is Pro-Life is Anti-Choice and his opponent who is Pro-Choice is Anti-Life, 30 seconds of sincere contemplation reveals how absurd this would be. What underlies the pro-choice position? And more importantly, what underlies the particular pro-choice position of the person you are speaking to? Not all pro-choicers think the same. Before arguing, ask questions so that a) you can better understand the root of their position, and b) so you can have a more productive conversation about the root beliefs.

A skilled therapist does this. She is able to listen to many stories and claims and accusations and ask questions that allow her to get to the bottom of all of them. Again, none of them

The majority of the Talmud an intergenerational recording of legal debates that involve bringing evidence and building logical arguments. There is, however, another form of rabbinic literature called “Aggadta” or “Midrash,” which is entirely different, even though the Talmud seamlessly weaves patches of it in between its legal debates. Midrash is a form of parable that is meant to convey deep philosophical, mystical, and ethical truths in highly evocative imagery that stimulates curiosity and deeper thought. It’s easier to show rather than tell what Midrash is. Here’s one pertinent to our topic: Midrashic parable:

When Jacob died in Egypt, the Pharaoh at the time wanted to afford Jacob honor and allowed Jacob’s sons to lead a royal funeral procession to the city of Hebron in what later became known as the Land of Israel. In Hebron was the Machpela Cave the burial site of Jacob’s wife Leah, his parents Isaac and Rebecca, and grandparents Abraham and Sarah. (So far these are all facts from the actual text of the Torah. Here is where the Midrashic parable begins.)

When they arrived to the Cave of Machpelah, Esav, Jacob’s brother and archenemy comes to stir up problems, announcing, “the Cave of Machpelah is mine,” (which of course it wasn’t). What did Joseph do? He sent Naphtali to travel quickly back down to Egypt to bring up the deed which was between them.

Meanwhile, Chushim, the son of Dan, who was impaired in his hearing and speech, said to them, “Why are we just sitting here?!” He was pointing [at Esav] with his finger. They said to him, “Because this man will not let us bury our father Jacob.”

What did he do? He drew his sword and cut off Esav’s head with the sword, and took the head into the Cave of Machpelah. They sent his body to the land of his possession, to Mount Seir.