A Calling

that is personal

When the Yom Kippur War broke out, just over 50 years ago on October 6, 1973, Leonard Cohen, the Canadian singer-songwriter was living a fairly reclusive life on a Greek island, waiting for an epiphany.

Cohen had grown up in a traditional Jewish home and community in Montreal. His parents were quite involved in the Shaar Hashomayim Congregation. His paternal grandfather Lyon Cohen was the founding president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, and his mother’s father was Rav Shlomo Zalman Klonitsky-Kline, a Talmud scholar, known by many as the “Prince of Hebrew Grammar,” with whom young Leonard Cohen enjoyed regular Torah study chavruta sessions. As Cohen grew older, he grew estranged from his tradition. In his 30s, he got into Zen Buddhism, and even became a monk. He didn’t, however, lose his deep affinity for Jewish spirituality, nor his identity as an eternal member of the Jewish people.

In 1964, about a decade before the Yom Kippur War, he was asked to speak to the Montreal Jewish community about his relationship to Judaism. He didn’t mince words in that speech, mourning what he perceived as the loss of the mission-driven “Judaism of the prophets,” in exchange for what he saw as a stagnant, ritualized shell of what once was. We can only imagine that this remained the spiritual backdrop of his life ten years later, still living on the Aegean Sea, waiting to be called upon “by the Infinite” to do something of true significance.

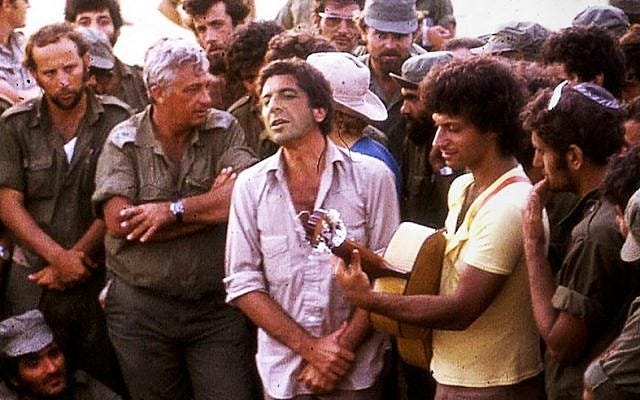

For Leonard Cohen, the surprise attack on Israel by Egyptian and Syrian forces, on the holiest day of the year in 1973, was that calling. Without any plan, he got on a plane to Tel Aviv. Prior to the war, Cohen had voiced political views that could be categorized as “pro-Arab,” but he still felt that he had to “join his brothers in Israel.” While he was waiting for his next “transmission from heaven” as to what he should do more specifically than just “be in Israel,” he was spotted in the Pinati Café by three Israeli musicians. They invited him to join them in the Sinai desert to sing for Israeli soldiers. He agreed. This was the calling he was waiting for. They played impromptu concerts to inspire IDF troops, but it was Cohen who came away from the experience more inspired than anyone else. Less than a year later, he came out with his first album in three years, New Skin for the Old Ceremony, which was clearly about his newly invigorated relationship with the Jewish spirit (take, for example, the song “Who By Fire,” which was directly based on the Yom Kippur prayer “Unetaneh Tokef”).

Leonard Cohen’s experience as a disillusioned Jew in the Diaspora, secretly longing for his spiritual calling was unique in its particularities, but in many ways, it is the story of so many Jews.

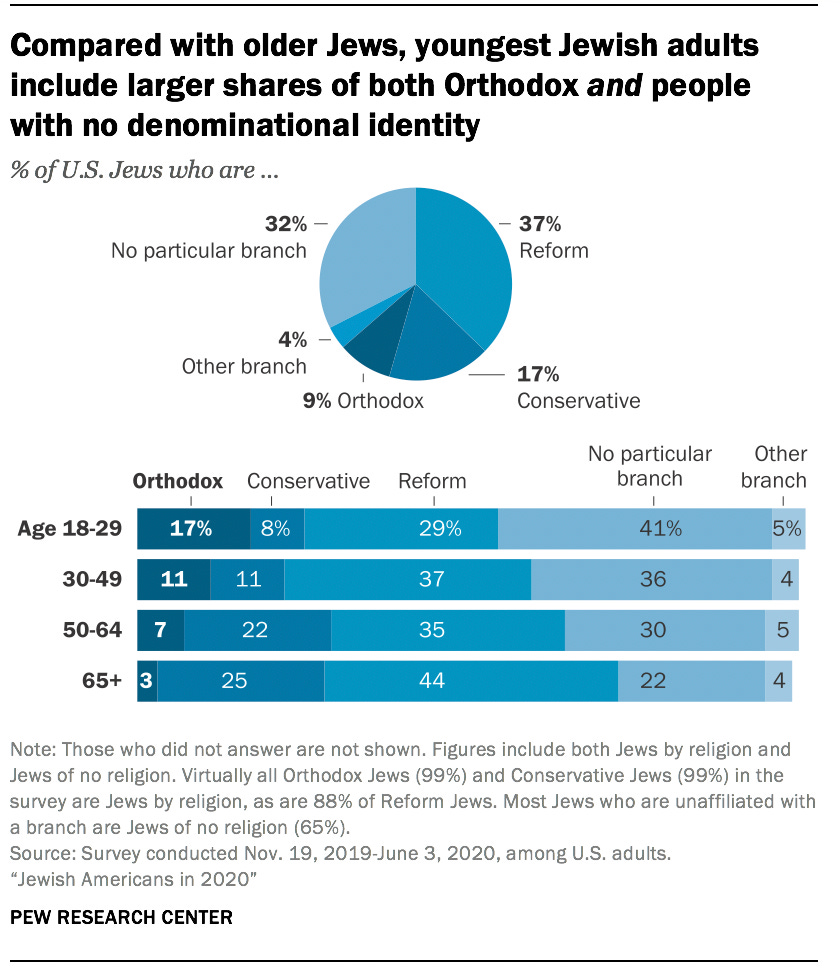

The percentage of self-identifying Orthodox Jews in the United States among the 18-29 demographic is growing due to relatively high birth rates, a strong focus on Jewish education, and global outreach efforts. But according to the 2020 Pew survey of American Jews, the percentage of Jews reporting “no particular affiliation” is growing at more or less the same pace.

Many young Jews seem to feel increasingly disconnected from any role they see within their Jewish communities. This phenomenon is also at work within the Orthodox community, albeit more quietly. Externally, a large number of young people might be showing up to their usual institutions, while internally they feel less and less connected.

What we need to bear in mind is that the purpose is the stuff of the soul, and the vacuum of purpose and meaning needs to be filled with something. If Judaism fails to fill that void, you can be sure that something else eventually will.

What’s at the root of this phenomenon of disconnection? And how can we combat it?

In the 1740s, the Italian Kabbalist and teacher Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (Ramchal) published what later became one of the central Jewish texts of Mussar (character development), known as the Mesilat Yesharim, which literally translates as “the path of those who walk straight ahead.” This work was the culmination of Ramchal’s frustrations with the Torah educational system in Europe, which he felt was producing too many scholars majoring in minor subjects, and a dismal few who weren’t using their careers to “hide from their personal mission,” as he describes in the book’s introduction.

The Mesilat Yesharim is essentially a step-by-step guide for how a person can cultivate a Judaism that stays real and vibrant by focusing on what is expected from him or her personally. We want to share two of his insights in the first chapter of the book, emerging from two deceptively simple words, which we believe can be guiding lights for us as parents, teachers and leaders as we guide our children, students and communities. Especially during this time of war, people around the world are being stirred to do something, but many still don’t know what exactly they should be doing. Young people are hearing a calling right now, and they look to us for how they can respond in a way that is authentic to them. We can’t miss the opportunity.

The opening line of Chapter 1 sets up the key to living a life energized with purpose is for a person to “clarify and take to heart what is his personal mission in his personal world.” The word Ramchal uses for “his mission” is חובתו, which literally means “his debt.” Every person in the world was born with a unique set of gifts from God, and receives new gifts from Him every day. Except they’re not just gifts. They’re unique debts that need to be paid — not back — because God doesn’t need them Himself — but forward — for the benefit of others. Judaism is often seen as a sweeping national obligation, which, of course, it is. But in order for a person to feel connected to this project known as the Jewish people, every person needs to see clearly and feel deeply what he or she should be doing with their gifts. Ramchal’s opening piece of advice is: start by looking at your gifts.

You can be sure that what you’re supposed to fix in the world has to do with the particular tools that have been placed in your hands.

Leonard Cohen knew he had to sing. What tools do you have in your hands waiting to be used?

The second nuance in Ramchal's words that makes a world of difference is that everyone’s personal mission has to play out in עולמו — his personal world. Two people may have the same set of gifts, but if they live in very different corners of the world, the way they use those gifts can be radically different. Take a good look at the unique needs of your corner of the world — your community, your environment, your friends, your acquaintances and your neighbors. Once you’ve identified the tools in your hands, you still have to open your eyes to the problems that need fixing where your Creator has very deliberately placed you.

One of the problems we face in our modern world — and our children and students even more than we do — is the barrage of information. When do young people have time today to take stock of their own gifts, if they are constantly being broadcast the gifts of others?

In our increasingly globalized world, young people also tend to look towards more exotic locations to volunteer and “save the world” before they look at what they can do with their gifts in their local communities.

What results from this is a confusing place for young people to find themselves and their personal purpose.

Imagine being an infantry soldier in the war in Gaza, approaching Gaza City on foot, hearing bullets whizz through the air, feeling the ground shake under your feet from the bombs dropped on Hamas infrastructure, seeing plumes of smoke rise up into the sky, in total astonishment that rocket after rocket continues to be fired overhead towards your friends and family members in Israel, and still with the pit in your stomach that two hundred and forty hostages are being held in what you can only imagine are dismal conditions by the ruthless terrorists who slaughtered over 1400 of your people a couple of months ago.

And yet, despite the normal and natural fear, every cell in your body is telling you to keep marching straight ahead (yashar) and do something worthwhile. This is your moment. You want to do your part in this war. You want to protect your family, your people, and your homeland from this monster that has been recognized for what it is.

Imagine, though, that on your radio, what you hear all day is a chaotic jumble of orders meant for air force pilots, mixed together with orders to navy sailors firing on the Gazan coast, instructions to special forces commandos on missions to penetrate tunnels, coordinates for snipers located on rooftops across the Strip, and a confusing mix of orders for tank drivers who are being asked to charge forward and others to take their tanks back across the border for maintenance.

Imagine hearing all of those orders and struggling to make out: which ones are meant for you?

How would you feel?

Confused.

Frustrated.

Exhausted.

In addition to sadness, anger and anxiety, these are emotions that many Jews around the world have felt since the war broke out.

Especially in the Diaspora, many Jews have felt at a loss for how they can contribute — how they can make a difference. Naturally, even those who have not felt stirred to do something in the past feel a calling now. The question is not “if they should do something,” but “what should they do?” Those who can’t draft into the IDF, don’t know where to find military-grade helmets and bulletproof vests, and don’t see themselves becoming social media influencers anytime soon — may feel a bit lost right now. The background noise of what everyone else is doing can be very inspiring, but also very distracting if one doesn’t know what he or she should be doing themselves.

If you have children, students or community members who look to you for guidance, know that right now, a very deep part of them is looking not just for general advice, but for specific direction.

Everyone knows they possess gifts, and are itching to use them for good, but they could use your support, insight and perspective to figure out how to practically do that. Everyone at least intuits that they are uniquely positioned to make some sort of strategic advance for the good of the Jewish nation and the world, but most need help seeing the opportunities that are right in front of them. This is the sacred role that we all have to play in this global effort.